Play & Book Excerpts

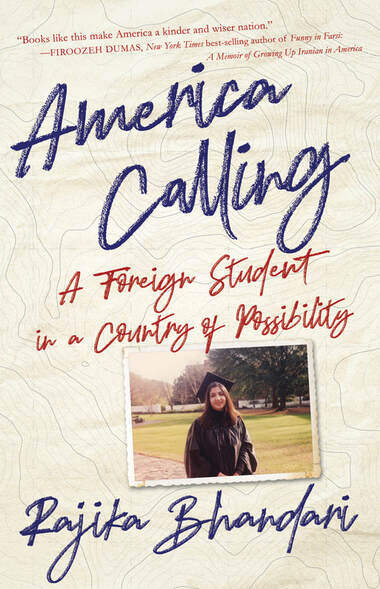

America Calling: A Foreign Student in a Country of Possibility

(She Writes Press)

© Rajika Bhandari

Excerpt from the chapter "Two Suitcases"

I felt tiny on the stage of the large auditorium as I looked up at the two hundred young freshmen who stared back at me. The glare of the lights hurt my eyes, but I could discern row after row of mostly white faces as they looked at me expectantly. Some sat slouched in their seats, their baseball hats cocked to the side, while others leaned forward, tapping their pencils impatiently on their notepads. It was 1:00 p.m. on a Tuesday, eastern standard time. I had arrived in Raleigh, North Carolina, from India less than forty-eight hours ago, traveling across two oceans and 8,500 miles. I had yet to find a place to live. But here I stood, before these American students, as they and I sized each other up.

My heartbeat pounded in my ears, my mouth was dry, and I felt a telltale flush rising from my neck to my face. They were waiting, as was the professor in the wings of the auditorium. I forced a smile, took a deep breath, and pulled back my shoulders. I positioned myself behind the mike at the podium.

“Good morning. Welcome to Introduction to Psychology 101. Dr. Broussard is your professor, but I’m your teaching assistant, Rajika Bhandari.” Perhaps it was my imagination, but I detected a collective eye roll: Great, we’re stuck with a TA with an accent.

I pushed on.

“I’ll play a brief recording for you. Based on what you hear, please write down three things you associate with the voice.” Professor Broussard liked to start the semester in a dramatic and unexpected way and had chosen to begin his first class with a small experiment in social psychology that revealed how we often form judgments about people based on their voices and accents. It had fallen to me to introduce the students to the class. I turned away from the mike, went into the wings, and pressed “play” on the audio-visual console. The tape began to run, and the professor’s stentorian voice boomed through the auditorium’s speakers. I watched the students listening carefully to the disembodied voice, trying to fit an image to the words. And I couldn’t help but wonder what first impressions the students had formed of me. I wondered how I appeared to them in my carefully selected outfit of purple culottes, a printed cotton top, and my green suede flats, a young and foreign woman just a few years older than most of them.

Forty-eight hours ago, Vikram and I had left Delhi on an American Airlines flight that departed at 2:00 a.m. from Indira Gandhi International Airport. On the drive to the airport in my aunt’s white Maruti Omni van, I clutched my mother’s hand and counted the highway signs as they brought me closer and closer to the terminal. The only other vehicles on the road were the lumbering trucks traveling inter-state and people like us, headed to the airport to put themselves or their loved ones on a plane that would transport them thousands of miles away.

The van pulled up outside the departure terminal. Vikram and his parents met us near the Air India counter where we were to check in. I pressed my mother’s hand, though I don’t know what I was reassuring her about. My mother was used to these sorts of moments, alone in her times of joy and sadness.

The only other people at the terminal were the female janitors in their khaki salwar suit uniforms, mopping the airport floor, and the passengers waiting with their families, the tears in their eyes now replaced with the emotional and physical exhaustion of staying up all night. The sterile, white glow of the fluorescent tube lights didn’t help. At that unearthly hour there was no daylight to make everything seem just a little bit less sad, less final.

For the journey I dressed in what I imagined a smart, westward-bound student might wear—faded jeans and a red shirt with a scarf—and I carried a tote bag with a blue paisley print. My two large suitcases, the maximum allowed by the airline, were now checked in. We had spent the past month carefully amassing the things I might need in America that could be contained in just two pieces of luggage. There were the clothes that I thought would suit a young, Indian graduate student in the US—jeans, tops, cotton skirts, and dresses—and for special occasions my mother carefully selected five silk saris with their matching blouses and petticoats. And then there was Parachute coconut hair oil, packets of henna for my hair, Shahnaz Hussain’s herbal beauty products, dried fruits and nuts, and spices. We bought and packed enough to last me a year, which is when I planned to be back.

All the packing and planning had led up to the night before, which I spent clinging to my mother like a baby, inhaling her unique scent tinged with the Pond’s sandalwood talcum powder she had used for years. But now with our bags checked and boarding passes issued, it was time for our final goodbyes and I hugged my mother tightly. By the time I left India that night, my mother and I were used to our frequent partings—I had spent a large part of my twenty-two years away from home in boarding schools that offered a better-quality education and then at a top university in the large metropolis of Delhi.

Yet going away to America was different. For the first time, we would be separated by almost ten thousand miles and different time zones, a chasm that we promised to bridge through phone calls and letters. I had often waved goodbye to my mother, my face and raised hand framed in the rectangular and grimy windows of trains and buses, but this time it was at the final immigration barrier in the airport.

I turned back for a last glimpse of her anxious face, not knowing when I might see her again, knowing only that the next time I spoke to her she would be a disembodied voice at the end of a telephone line half a world away. She would be here—in India—and I would be there— in America—and there was very little in between that could change that indelible truth.

My heartbeat pounded in my ears, my mouth was dry, and I felt a telltale flush rising from my neck to my face. They were waiting, as was the professor in the wings of the auditorium. I forced a smile, took a deep breath, and pulled back my shoulders. I positioned myself behind the mike at the podium.

“Good morning. Welcome to Introduction to Psychology 101. Dr. Broussard is your professor, but I’m your teaching assistant, Rajika Bhandari.” Perhaps it was my imagination, but I detected a collective eye roll: Great, we’re stuck with a TA with an accent.

I pushed on.

“I’ll play a brief recording for you. Based on what you hear, please write down three things you associate with the voice.” Professor Broussard liked to start the semester in a dramatic and unexpected way and had chosen to begin his first class with a small experiment in social psychology that revealed how we often form judgments about people based on their voices and accents. It had fallen to me to introduce the students to the class. I turned away from the mike, went into the wings, and pressed “play” on the audio-visual console. The tape began to run, and the professor’s stentorian voice boomed through the auditorium’s speakers. I watched the students listening carefully to the disembodied voice, trying to fit an image to the words. And I couldn’t help but wonder what first impressions the students had formed of me. I wondered how I appeared to them in my carefully selected outfit of purple culottes, a printed cotton top, and my green suede flats, a young and foreign woman just a few years older than most of them.

Forty-eight hours ago, Vikram and I had left Delhi on an American Airlines flight that departed at 2:00 a.m. from Indira Gandhi International Airport. On the drive to the airport in my aunt’s white Maruti Omni van, I clutched my mother’s hand and counted the highway signs as they brought me closer and closer to the terminal. The only other vehicles on the road were the lumbering trucks traveling inter-state and people like us, headed to the airport to put themselves or their loved ones on a plane that would transport them thousands of miles away.

The van pulled up outside the departure terminal. Vikram and his parents met us near the Air India counter where we were to check in. I pressed my mother’s hand, though I don’t know what I was reassuring her about. My mother was used to these sorts of moments, alone in her times of joy and sadness.

The only other people at the terminal were the female janitors in their khaki salwar suit uniforms, mopping the airport floor, and the passengers waiting with their families, the tears in their eyes now replaced with the emotional and physical exhaustion of staying up all night. The sterile, white glow of the fluorescent tube lights didn’t help. At that unearthly hour there was no daylight to make everything seem just a little bit less sad, less final.

For the journey I dressed in what I imagined a smart, westward-bound student might wear—faded jeans and a red shirt with a scarf—and I carried a tote bag with a blue paisley print. My two large suitcases, the maximum allowed by the airline, were now checked in. We had spent the past month carefully amassing the things I might need in America that could be contained in just two pieces of luggage. There were the clothes that I thought would suit a young, Indian graduate student in the US—jeans, tops, cotton skirts, and dresses—and for special occasions my mother carefully selected five silk saris with their matching blouses and petticoats. And then there was Parachute coconut hair oil, packets of henna for my hair, Shahnaz Hussain’s herbal beauty products, dried fruits and nuts, and spices. We bought and packed enough to last me a year, which is when I planned to be back.

All the packing and planning had led up to the night before, which I spent clinging to my mother like a baby, inhaling her unique scent tinged with the Pond’s sandalwood talcum powder she had used for years. But now with our bags checked and boarding passes issued, it was time for our final goodbyes and I hugged my mother tightly. By the time I left India that night, my mother and I were used to our frequent partings—I had spent a large part of my twenty-two years away from home in boarding schools that offered a better-quality education and then at a top university in the large metropolis of Delhi.

Yet going away to America was different. For the first time, we would be separated by almost ten thousand miles and different time zones, a chasm that we promised to bridge through phone calls and letters. I had often waved goodbye to my mother, my face and raised hand framed in the rectangular and grimy windows of trains and buses, but this time it was at the final immigration barrier in the airport.

I turned back for a last glimpse of her anxious face, not knowing when I might see her again, knowing only that the next time I spoke to her she would be a disembodied voice at the end of a telephone line half a world away. She would be here—in India—and I would be there— in America—and there was very little in between that could change that indelible truth.

|

Rajika Bhandari, Ph.D., is the author of the new book, America Calling: A Foreign Student in a Country of Possibility. A former international student from India to the U.S. and an Indian American immigrant, Rajika is an international higher education expert, a widely published author, and a sought-after speaker on issues of international education, skilled immigrants, and educational and cultural diplomacy.

An author of five academic books and one previous nonfiction book, The Raj on the Move: Story of the Dak Bungalow, she is quoted by dozens of global media outlets each year, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Times of India, The Economic Times, and Quartz, and her writing has appeared in Ms. Magazine, The Guardian, The Chronicle of Higher Education, HuffPost, University World News, Times Higher Education, National Geographic Traveler and The Diplomatic Courier, among others. Rajika lives outside of New York City. |