April 2022 Featured Interview

Women and Girls on the Spectrum:

Diagnosis, Challenges and Transitions

Interview with

Laura Lee McIntyre, Ph.D.

Interim Dean for the College of Education & Castle-McIntosh-Knight Professor, University of Oregon

Photo Courtesy: University of Oregon

About Laura Lee:

Laura Lee McIntyre, Ph.D., BCBA-D, is the interim dean for the College of Education and Castle-McIntosh-Knight Professor at the University of Oregon.

She is known for her work in autism, family-centered interventions, and family–school partnerships for children with disabilities. Laura Lee is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), certified school psychologist, and board licensed psychologist.

She has professional experiences in both school and hospital settings. Prior to joining the faculty at the University of Oregon, she was a faculty member in the Psychology Department at Syracuse University and an affiliated faculty member in the Center for Development, Behavior, and Genetics in the Department of Pediatrics at SUNY Upstate Medical University.

She is known for her work in autism, family-centered interventions, and family–school partnerships for children with disabilities. Laura Lee is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), certified school psychologist, and board licensed psychologist.

She has professional experiences in both school and hospital settings. Prior to joining the faculty at the University of Oregon, she was a faculty member in the Psychology Department at Syracuse University and an affiliated faculty member in the Center for Development, Behavior, and Genetics in the Department of Pediatrics at SUNY Upstate Medical University.

Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor, spoke with Laura Lee about how autism presents in girls, the special challenges faced by many adolescents and adult women on the spectrum, and what parents can do to help with life’s transitions.

Girls are still being diagnosed with autism at lower rates than boys. What are some of the reasons for this?

There are a couple of factors. One is the bias many professionals have that ASD [autism spectrum disorder] exists [predominantly] in boys. Unfortunately, that bias can affect and impact all aspects of the service delivery system. Daycare providers might be more tuned into looking at behaviors – such as communication and social difficulties – in boys. There’s also a bias with our physicians and pediatrician community simply because the prevalence rates to date have continued to show higher diagnosis in boys.

[The male to female ratio is often listed as 4:1, but some recent studies show it might be closer to 3:1 due to gender bias, meaning that girls who meet criteria for ASD are at disproportionate risk of not receiving a clinical diagnosis. NIH, National Library of Medicine].

And does autism present differently in girls?

ASD is thought of as a white, male disorder, and that simply is not true. But, in addition to gender, there are disparities in terms of race, ethnicity, language, and social class.

More recently, there has been a body of research focused on the notion of social camouflaging. Girls can mimic the social cues and communication patterns of others without fully understanding what they’re saying, what they’re doing, and why. But it’s superficial, not a deep understanding of communication skills.

From my experience, social differences become much more salient during the transition to adolescence (10 to 14 years of age). Self-regulation is how we adapt to day-to-day challenges, and [self-regulation is certainly a challenge for those on the spectrum]. One might think of the autistic boy as having huge meltdowns or being more aggressive. Stereotypically, the autistic girl might be more inwardly directed or more over-regulated in terms of not developing healthy coping skills. Girls on the spectrum can also fly under the radar if they are hyperlexic or hyperverbal. They may be performing well in school and not ‘acting out.’ Therefore, they are not displaying some of those typical ‘red flags’ that teachers and other professionals look for.

But I’m painting with a broad brush here. It is a huge spectrum, and it makes it difficult for everyone – teachers, parents, physicians – because it’s not a one-size-fits-all, not even a one-size-fits-most. And, of course, adolescence is a difficult time for everyone.

Girls are still being diagnosed with autism at lower rates than boys. What are some of the reasons for this?

There are a couple of factors. One is the bias many professionals have that ASD [autism spectrum disorder] exists [predominantly] in boys. Unfortunately, that bias can affect and impact all aspects of the service delivery system. Daycare providers might be more tuned into looking at behaviors – such as communication and social difficulties – in boys. There’s also a bias with our physicians and pediatrician community simply because the prevalence rates to date have continued to show higher diagnosis in boys.

[The male to female ratio is often listed as 4:1, but some recent studies show it might be closer to 3:1 due to gender bias, meaning that girls who meet criteria for ASD are at disproportionate risk of not receiving a clinical diagnosis. NIH, National Library of Medicine].

And does autism present differently in girls?

ASD is thought of as a white, male disorder, and that simply is not true. But, in addition to gender, there are disparities in terms of race, ethnicity, language, and social class.

More recently, there has been a body of research focused on the notion of social camouflaging. Girls can mimic the social cues and communication patterns of others without fully understanding what they’re saying, what they’re doing, and why. But it’s superficial, not a deep understanding of communication skills.

From my experience, social differences become much more salient during the transition to adolescence (10 to 14 years of age). Self-regulation is how we adapt to day-to-day challenges, and [self-regulation is certainly a challenge for those on the spectrum]. One might think of the autistic boy as having huge meltdowns or being more aggressive. Stereotypically, the autistic girl might be more inwardly directed or more over-regulated in terms of not developing healthy coping skills. Girls on the spectrum can also fly under the radar if they are hyperlexic or hyperverbal. They may be performing well in school and not ‘acting out.’ Therefore, they are not displaying some of those typical ‘red flags’ that teachers and other professionals look for.

But I’m painting with a broad brush here. It is a huge spectrum, and it makes it difficult for everyone – teachers, parents, physicians – because it’s not a one-size-fits-all, not even a one-size-fits-most. And, of course, adolescence is a difficult time for everyone.

Many girls are not diagnosed until their teen years or even into adulthood. What are some of the ramifications of late diagnosis?

There are a couple of big ramifications. The first falls into the practical bucket of lost services, critical early interventions and supports for the individual and for the family. When there is early intervention, you get more bang for your buck because the brain is still developing.

There are missed opportunities for the family or support network to develop an understanding of what’s going on. When you arrive to the party late, you are playing catch-up. There can be parental guilt, too. The parent might say, ‘How did I miss this? I thought I knew my child.’

You also need to look at the impact on the individual. The individual is trying to come to terms with who she is. What makes me tick? How do I relate to the world? The adolescent period is a soul-searching period of autonomy, a time to differentiate oneself from others. Adolescents are also aligning themselves with their peers. At this stage, the peer group becomes a much more powerful factor in shaping who you are.

For the autistic teen, it’s important to understand how she sees the world differently from neurotypicals – it’s not bad, just different. This is so important for identity and self-compassion. I’ve seen some young women who were diagnosed late, and the lightbulb goes off. The reaction: Aha! Now I understand. Now I am not ashamed. I just process the world differently.

There are a couple of big ramifications. The first falls into the practical bucket of lost services, critical early interventions and supports for the individual and for the family. When there is early intervention, you get more bang for your buck because the brain is still developing.

There are missed opportunities for the family or support network to develop an understanding of what’s going on. When you arrive to the party late, you are playing catch-up. There can be parental guilt, too. The parent might say, ‘How did I miss this? I thought I knew my child.’

You also need to look at the impact on the individual. The individual is trying to come to terms with who she is. What makes me tick? How do I relate to the world? The adolescent period is a soul-searching period of autonomy, a time to differentiate oneself from others. Adolescents are also aligning themselves with their peers. At this stage, the peer group becomes a much more powerful factor in shaping who you are.

For the autistic teen, it’s important to understand how she sees the world differently from neurotypicals – it’s not bad, just different. This is so important for identity and self-compassion. I’ve seen some young women who were diagnosed late, and the lightbulb goes off. The reaction: Aha! Now I understand. Now I am not ashamed. I just process the world differently.

|

When things happen to us, and we don’t understand, then we feel helpless and lost. Sometimes with information comes power. That reframing can bring acceptance and can help the individual develop coping strategies and, perhaps, to find her ‘people. Late diagnoses will happen, but once we have an explanation that makes sense to the individual and their network, it helps to rewrite the story. Your glass is not half empty, you are just drinking from a different glass!

How do issues such as lack of self-control and anxiety manifest in adulthood? I’ve seen some teens transition to adulthood pretty well, and I’ve seen others really struggle. |

"Late diagnoses will happen, but once we have an explanation that makes sense to the individual and their network, it helps to rewrite the story. Your glass is not half empty, you are just drinking from a different glass!" |

There are a lot of reasons why we see different outcomes. Part of it may be the individual and the coping skills they may or may not have developed over the years. Social support matters. We need at least one person where we feel safe to be ourselves. Holding it together at work or school can bring on anxiety which can build up and become debilitating, which may also become a significant impediment to social relationships in the workplace.

This is when trusted childhood friends, family members and others can play a support role a bit longer.

What are some typical challenges that arise in the workplace for women on the spectrum? Is it important for a woman on the spectrum to find a support person or mentor on the job?

There are plenty of challenges depending on what the workplace is like. Choosing the right environment is imperative. Not everyone is going to do well in an office setting. Knowing yourself and what you need is so important.

Finding a mentor is important, but it doesn’t have to be someone at the workplace. Sometimes you might not find a mentor there. Maybe you haven’t connected with anyone, or you have preferred not to disclose. Sometimes it’s not safe to disclose. This is especially true for young women who feel more vulnerable to being passed over for raises or promotions.

What are some typical challenges that arise in the workplace for women on the spectrum? Is it important for a woman on the spectrum to find a support person or mentor on the job?

There are plenty of challenges depending on what the workplace is like. Choosing the right environment is imperative. Not everyone is going to do well in an office setting. Knowing yourself and what you need is so important.

Finding a mentor is important, but it doesn’t have to be someone at the workplace. Sometimes you might not find a mentor there. Maybe you haven’t connected with anyone, or you have preferred not to disclose. Sometimes it’s not safe to disclose. This is especially true for young women who feel more vulnerable to being passed over for raises or promotions.

|

"Sometimes it’s good just to do a comprehension check: I heard it this way. Is that what you meant? Another trick is repeating instructions back. Workplace tips and tricks work for everyone." |

However, if you can find a trusted colleague or mentor at the workplace, it can be a very helpful relationship.

Sometimes it’s good just to do a comprehension check: I heard it this way. Is that what you meant? Another trick is repeating instructions back. Workplace tips and tricks work for everyone. At the end of the meeting, you can say something like, ‘Let me just confirm that the next steps are a, b and c.’ I think what happens in a work environment – just like any environment – is that there are ambiguous social cues that neurotypicals pick up on because they’re tuned into some of those things that are more implicit, those non-verbal forms of communication. |

A parent of a child on the spectrum is used to being her child’s support system and advocate. How should the parent-child relationship change in adulthood? How much should a parent let go of managing decisions?

Parents need to learn to let some of the control go. They need to find that balance of helping their child launch into adulthood, but also being in the background as a solid rock, so to speak, or that person their child is free to vent to.

In general, today’s young adults stay at home longer and rely on their parents more when compared to a few generations ago.

Laura Lee explained that it’s difficult for many parents to give up control as their children begin to navigate adulthood.

Parents need to let their child take that risk and let her know that it is okay to fail, that [it’s brave to try new things and learn from them regardless of the outcome]. A parent of an autistic child is used to being that protector, that advocate for so many years, and it’s even harder to navigate that transition.

This starts before transition to adulthood, though. It should happen little by little as a child develops. All of those firsts you helped your child to prepare for are part of the equation. It’s so important to learn to accept failure and to develop a growth mindset. Maybe I didn’t win this time, but I believed in myself, and I learned something. Normalize that it’s okay to make mistakes. Perfectionism fuels anxiety. Take baby steps and start early.

Parents need to learn to let some of the control go. They need to find that balance of helping their child launch into adulthood, but also being in the background as a solid rock, so to speak, or that person their child is free to vent to.

In general, today’s young adults stay at home longer and rely on their parents more when compared to a few generations ago.

Laura Lee explained that it’s difficult for many parents to give up control as their children begin to navigate adulthood.

Parents need to let their child take that risk and let her know that it is okay to fail, that [it’s brave to try new things and learn from them regardless of the outcome]. A parent of an autistic child is used to being that protector, that advocate for so many years, and it’s even harder to navigate that transition.

This starts before transition to adulthood, though. It should happen little by little as a child develops. All of those firsts you helped your child to prepare for are part of the equation. It’s so important to learn to accept failure and to develop a growth mindset. Maybe I didn’t win this time, but I believed in myself, and I learned something. Normalize that it’s okay to make mistakes. Perfectionism fuels anxiety. Take baby steps and start early.

|

What services does the University of Oregon’s HEDCO Clinic provide?

It is a research clinic* which provides services mainly for children and adolescents and their parents. It is interdisciplinary. We have diagnostic assessment, speech services, social services and mental health services. We work with school districts and families. It is a community program. Transition to adulthood and adult services are provided by our Center on Human Development. This is through our College of Education. We have a big focus on secondary transition to adult services. *HEDCO is a state-of-the-art university training clinic comprised of educators, psychologists, therapists, and faculty researchers working as a team to provide the highest quality evidence-based assessment and treatment behavioral health services to individuals and their families. |

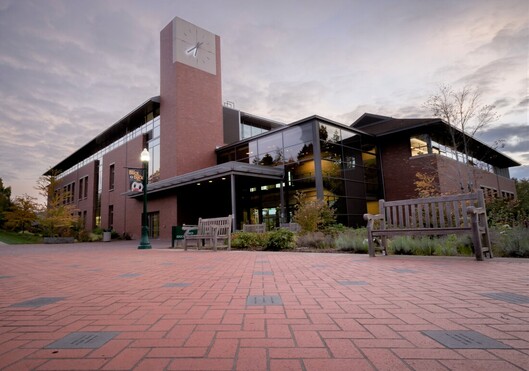

HEDCO Building

Photo Courtesy: University of Oregon |

What types of outreach services does the University of Oregon's Autism Interest Group (AIG) provide for the community?

This is a great example of students, faculty, staff, and community members working together to provide social support, academic support, and recreational opportunities for those on the spectrum as well as information for anyone who wants to learn more. It’s an interesting and fascinating collective which includes students and faculty on the spectrum. There is information sharing and science talks. It has grown over time. It’s not a formal group, but it is evolving and plays a variety of roles.

The Autism Interest Group (AIG) at the University of Oregon was founded in 2007 by Professor Phil Washbourne. In the club’s early years, AIG focused on giving scientific talks that were open to the public. Previous talks highlighted research in human cognition, research in human genomics, parents sharing their personal experiences, and more. The current goal of AIG is to increase outreach efforts throughout the University of Oregon and the broader Eugene area.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I love to run. I find my peace and my sanctuary when I lose myself on a trail somewhere. This brings me closer to my inner peace. I also find sanctuary hanging out with my kids and my family – especially when we’re active doing something outside. I’m married and have two children. I just get caught up in the moment with them.

This is a great example of students, faculty, staff, and community members working together to provide social support, academic support, and recreational opportunities for those on the spectrum as well as information for anyone who wants to learn more. It’s an interesting and fascinating collective which includes students and faculty on the spectrum. There is information sharing and science talks. It has grown over time. It’s not a formal group, but it is evolving and plays a variety of roles.

The Autism Interest Group (AIG) at the University of Oregon was founded in 2007 by Professor Phil Washbourne. In the club’s early years, AIG focused on giving scientific talks that were open to the public. Previous talks highlighted research in human cognition, research in human genomics, parents sharing their personal experiences, and more. The current goal of AIG is to increase outreach efforts throughout the University of Oregon and the broader Eugene area.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I love to run. I find my peace and my sanctuary when I lose myself on a trail somewhere. This brings me closer to my inner peace. I also find sanctuary hanging out with my kids and my family – especially when we’re active doing something outside. I’m married and have two children. I just get caught up in the moment with them.

|

Recent news...

In March 2022, the University of Oregon announced the launch of The Ballmer Institute for Children’s Behavioral Health, a bold new approach to addressing the behavioral and mental health care needs of Oregon’s children. The Portland-based institute is made possible by a lead gift of more than $425 million from Connie and Steve Ballmer, co-founders of Ballmer Group Philanthropy. |