Play & Book Excerpts

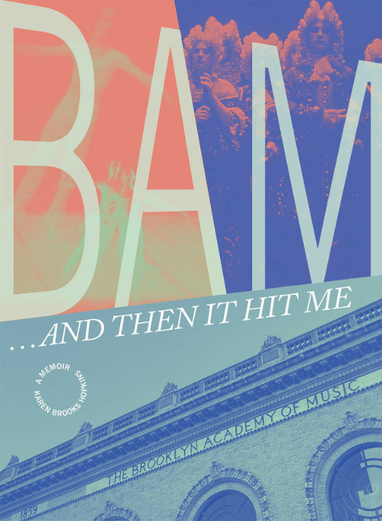

BAM...And Then It Hit Me

(powerHouse Books)

© Karen Brooks Hopkins

Find a short Q&A with Karen concerning life as a nonprofit leader.

EXCERPT:

The DanceAfrica Festival at BAM, which began in 1977, wasn’t just a program; it was a force. Charles (Chuck) Davis, dancer, griot, teacher, all around leader of people and champion of the arts brought the show to BAM and changed the Memorial Day weekend in Brooklyn forever. It was important—particularly in light of the neighborhood demographic—to put work on BAM’s stages that reflected racial diversity. Chuck Davis’s DanceAfrica brought that and so much more. The program, which began as a small showcase of African American dance companies has now grown over four decades and remains the centerpiece of Memorial Day weekend in New York.

To truly comprehend the scope of this event, it is important to understand the magnitude and charisma of Chuck Davis. He was a huge presence, well over six feet tall. He always wore the traditional multi-colored African robes and headwear that defined him as a both Chief and inspiring leader. He had huge hands, long arms and emanated a warmth that touched everyone he met. First and foremost, he was a cheerleader for African dance. He believed that dance was not only the way to bring people together; it was the way to make them feel proud of and connected to their heritage. He was from North Carolina and his southern hospitality, combined with his knowledge of African traditions, defined the personality of DanceAfrica. He introduced each show and DanceAfrica gathering with the “Ago,” a greeting from the Ghanaian people of West Africa. He would bellow “AGO” or “listen” and the audience, at his instruction, would faithfully bellow back “AME!”—“I am (we are) listening.” Over the years the program kept growing and expanding both inside the building, outside on the streets around BAM, deep into Brooklyn and then to cities all over the United States.

At BAM, the DanceAfrica Festival is overseen by a distinguished Council of Elders who worked with Chuck all year long to select themes for the festival, and provide education programs related to dance and other African heritage events. We all referred to Chuck as “Baba” or “Father” in many African languages, and he made us feel like we were all his children. Every Memorial Day, our parking lots became an enormous African bazaar, with over 250 craft, food, and clothing vendors. It was common for close to fifty thousand people to attend the bazaar every year. Inside the Howard Gilman Opera House, the five performances scheduled for that weekend were always sold out. Every year we showcased not only African American companies, but also a company that came to BAM from a nation in Africa. There were master classes with the visiting African companies, related films in the BAM Rose Cinemas, talks, an emerging choreographers fellowship and scholarships for youth, dinners for the Elders, an official Memorial room, events at Weeksville Heritage Center, the African Burial grounds in Manhattan, and a massive education program.

The education program consisted of an in-depth partnership with Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (often called BSRC or Restoration). It is the oldest community development corporation in the country having opened in 1967, through the efforts of Robert Kennedy and Franklin Thomas, who served as the organization’s first president. In 1996, I decided to pay a visit to the Rev. Dr. Emma Jordan-Simpson, a senior executive at Restoration. It seemed strange that we didn’t know each other, given that both BAM and Restoration had been important organizations in their respective communities for decades. At our meeting, Emma and I cooked up a partnership that has become an integral part of the festival for over twenty-five years. We decided that each season, a group of young people would study the traditions and mores of the African country represented at that year’s festival, and learn a dance, which they would perform alongside the professional dancers on the opera house stage. The participants maintained good grades at school, attended all rehearsals, and remained fully engaged in the program, from beginning to end. The experience has been transformative and powerful, as hundreds of children have participated this initiative. Each year, the selected African company would come to BAM a week before the festivities to work directly with the young dancers. As part of the program, the students would make their costumes, learn their roles, and work diligently to produce a dance of the highest quality. The professionalism and style of these student performers has been off the charts. They have been invited to perform in many places beyond BAM and they (the BAM Restoration Dance Company) are a source of enormous pride to BSRC, BAM and all of Brooklyn.

Over the years, Chuck, bubbling with enthusiasm for each individual festival, also came up with some extravagant special additions to the program. There were a few particular festival events that I always recall joyfully. One time Chuck actually conducted a traditional African wedding ceremony onstage. He joined his loyal assistant stage manager, Normadien Woolbright, and N’Goma, our stage manager, in holy matrimony that day with the entire audience of over two thousand people in the opera house as witnesses. The couple is still together, and I have fond memories of their wedding day. In 1983, for the sixteenth anniversary, Chuck organized a group African American motorcyclists, called the Imperial Bikers Motorcycle Club, each rider bearing a flag of a different African nation, to drive in formation from Harlem to the steps of BAM. They were joined by the Council of Elders, artists, and dignitaries for a libation pouring ceremony, for which we commissioned a famous Brooklyn baker to bake an enormous red velvet cake in the shape of Africa, and we opened the doors for a huge public cake party. We also sometimes featured marching bands and teen break-dancers performing in front of the building. Baba Chuck loved the annual Brooklyn celebration but he wanted to spread the DanceAfrica message of “peace, love, and respect for everybody” far and wide. At one point we got an NEA grant to take the program all over the United States. We ended up touring the festival and adding local companies in each of our five destination cities around the nation. Many of those festivals and some new ones still exist today.

One year I arrived at BAM on the final day of the festival to see that police had cordoned off the area and that everything had been shut down on Lafayette Avenue. I dashed up to the door of the opera house, apprehensive about what might of happened, and learned that a gigantic swarm of bees had escaped from their owner’s hives and had taken up residence on the canopy of the opera house. There were millions of them. Even the bees couldn’t resist the sound of the drums.

The DanceAfrica Festival at BAM, which began in 1977, wasn’t just a program; it was a force. Charles (Chuck) Davis, dancer, griot, teacher, all around leader of people and champion of the arts brought the show to BAM and changed the Memorial Day weekend in Brooklyn forever. It was important—particularly in light of the neighborhood demographic—to put work on BAM’s stages that reflected racial diversity. Chuck Davis’s DanceAfrica brought that and so much more. The program, which began as a small showcase of African American dance companies has now grown over four decades and remains the centerpiece of Memorial Day weekend in New York.

To truly comprehend the scope of this event, it is important to understand the magnitude and charisma of Chuck Davis. He was a huge presence, well over six feet tall. He always wore the traditional multi-colored African robes and headwear that defined him as a both Chief and inspiring leader. He had huge hands, long arms and emanated a warmth that touched everyone he met. First and foremost, he was a cheerleader for African dance. He believed that dance was not only the way to bring people together; it was the way to make them feel proud of and connected to their heritage. He was from North Carolina and his southern hospitality, combined with his knowledge of African traditions, defined the personality of DanceAfrica. He introduced each show and DanceAfrica gathering with the “Ago,” a greeting from the Ghanaian people of West Africa. He would bellow “AGO” or “listen” and the audience, at his instruction, would faithfully bellow back “AME!”—“I am (we are) listening.” Over the years the program kept growing and expanding both inside the building, outside on the streets around BAM, deep into Brooklyn and then to cities all over the United States.

At BAM, the DanceAfrica Festival is overseen by a distinguished Council of Elders who worked with Chuck all year long to select themes for the festival, and provide education programs related to dance and other African heritage events. We all referred to Chuck as “Baba” or “Father” in many African languages, and he made us feel like we were all his children. Every Memorial Day, our parking lots became an enormous African bazaar, with over 250 craft, food, and clothing vendors. It was common for close to fifty thousand people to attend the bazaar every year. Inside the Howard Gilman Opera House, the five performances scheduled for that weekend were always sold out. Every year we showcased not only African American companies, but also a company that came to BAM from a nation in Africa. There were master classes with the visiting African companies, related films in the BAM Rose Cinemas, talks, an emerging choreographers fellowship and scholarships for youth, dinners for the Elders, an official Memorial room, events at Weeksville Heritage Center, the African Burial grounds in Manhattan, and a massive education program.

The education program consisted of an in-depth partnership with Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation (often called BSRC or Restoration). It is the oldest community development corporation in the country having opened in 1967, through the efforts of Robert Kennedy and Franklin Thomas, who served as the organization’s first president. In 1996, I decided to pay a visit to the Rev. Dr. Emma Jordan-Simpson, a senior executive at Restoration. It seemed strange that we didn’t know each other, given that both BAM and Restoration had been important organizations in their respective communities for decades. At our meeting, Emma and I cooked up a partnership that has become an integral part of the festival for over twenty-five years. We decided that each season, a group of young people would study the traditions and mores of the African country represented at that year’s festival, and learn a dance, which they would perform alongside the professional dancers on the opera house stage. The participants maintained good grades at school, attended all rehearsals, and remained fully engaged in the program, from beginning to end. The experience has been transformative and powerful, as hundreds of children have participated this initiative. Each year, the selected African company would come to BAM a week before the festivities to work directly with the young dancers. As part of the program, the students would make their costumes, learn their roles, and work diligently to produce a dance of the highest quality. The professionalism and style of these student performers has been off the charts. They have been invited to perform in many places beyond BAM and they (the BAM Restoration Dance Company) are a source of enormous pride to BSRC, BAM and all of Brooklyn.

Over the years, Chuck, bubbling with enthusiasm for each individual festival, also came up with some extravagant special additions to the program. There were a few particular festival events that I always recall joyfully. One time Chuck actually conducted a traditional African wedding ceremony onstage. He joined his loyal assistant stage manager, Normadien Woolbright, and N’Goma, our stage manager, in holy matrimony that day with the entire audience of over two thousand people in the opera house as witnesses. The couple is still together, and I have fond memories of their wedding day. In 1983, for the sixteenth anniversary, Chuck organized a group African American motorcyclists, called the Imperial Bikers Motorcycle Club, each rider bearing a flag of a different African nation, to drive in formation from Harlem to the steps of BAM. They were joined by the Council of Elders, artists, and dignitaries for a libation pouring ceremony, for which we commissioned a famous Brooklyn baker to bake an enormous red velvet cake in the shape of Africa, and we opened the doors for a huge public cake party. We also sometimes featured marching bands and teen break-dancers performing in front of the building. Baba Chuck loved the annual Brooklyn celebration but he wanted to spread the DanceAfrica message of “peace, love, and respect for everybody” far and wide. At one point we got an NEA grant to take the program all over the United States. We ended up touring the festival and adding local companies in each of our five destination cities around the nation. Many of those festivals and some new ones still exist today.

One year I arrived at BAM on the final day of the festival to see that police had cordoned off the area and that everything had been shut down on Lafayette Avenue. I dashed up to the door of the opera house, apprehensive about what might of happened, and learned that a gigantic swarm of bees had escaped from their owner’s hives and had taken up residence on the canopy of the opera house. There were millions of them. Even the bees couldn’t resist the sound of the drums.

|

Karen Brooks Hopkins was an employee of the Brooklyn Academy of Music (“BAM”) for 36 years, serving as its president from 1999 until retiring in 2015.

Karen is senior advisor and a board member of the Onassis Foundation, the Nasher Haemisegger Fellow at SMU DataArts located at Southern Methodist University from 2016-2021, and a board member of the Trust for Governors Island and the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. From 2015-2017, Karen served as Senior Fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Karen has been awarded honorary degrees from St. Francis College, Long Island University, Pratt Institute and Columbia University. She has also received international honors including the King Olav’s Medal from Norway, the Chevalier de L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from France and the Commander of the Royal Order of the Polar Star from Sweden. While at BAM, the institution received the National Medal of Arts from President Obama. |

Photo Credit: Bob Klein

|

UPCOMING AUTHOR EVENTS/SIGNINGS:

September 19, 2022 International Economic Development Conference Downtown Oklahoma City, OK September 29, 2022 Saratoga Performing Arts Center Saratoga, NY October 17 - 19, 2022 Keynote Speaker Annual Convention of the Cultural Forum & the City’s Program for Arts Administrators Tel Aviv, Israel |