Play & Book Excerpts

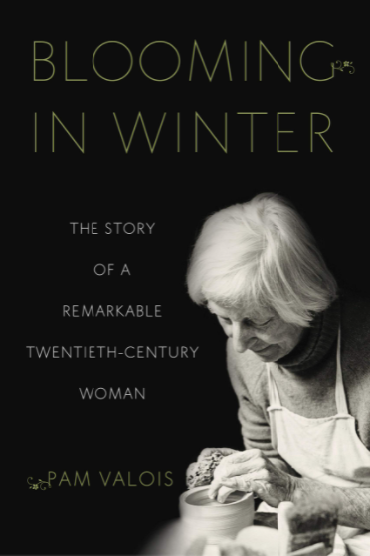

Blooming in Winter

(She Writes Press)

© Pamela Valois

In September 1923, Jackie—an optimistic country girl and the daughter of intrepid immigrants—took the train south to begin her college life.

The train clopped along tooting through the tunnels and the little towns. . . . Until San Rafael, then suddenly the sharp prick of eucalyptus and a mysterious breath of fog on the skin.

At the University of California, Berkeley, she met Florence Jury, who would become a lifelong friend. When my husband and I knew them in their late seventies, they depended on each other. Both widows, they called each other every morning to talk about plans for the day or breakfast

down the hill on Shattuck Avenue. Flo described meeting Jackie in their freshman year:

Sitting directly across the table from me was a tall, slender girl with curly golden hair and blue eyes the shade of the northern summer sky. Her face was different, not pretty,

but arresting and unforgettable in its planes and contours. It was no time at all before we were smoking an after-dinner cigaret [sic] under the outside stairs. . . . There was so much to talk about.

When Jackie came to Berkeley, the university was already considered one of America’s premier institutions of higher learning. UC Berkeley was on the map and was the heart of the community, much as it is today. The school had been coeducational since 1870, unusual for American universities at the time. California’s (male) voters, however, did not believe that attaining the age of majority was enough to qualify a woman to vote. They defeated a measure to establish female suffrage in 1896. Fifteen years later, just in time for Jackie’s generation, California became the sixth state in the United States to enfranchise women, presaging the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Having won the right to vote, the modern women of the twenties were exploring and adopting new values. They bobbed their hair, shortened their skirts, drank cocktails, and smoked. They mingled openly with men and burst onto the college scene in larger numbers than ever before. Corsets were swapped in favor of loose-fitting dresses that expressed their carefree spirit.

Jackie “tingled with excitement” as she stood in long lines to sign up for classes. With its mature trees and dirt paths, the campus reminded Jackie of the ranch.

Then near midday on September 17, 1923, Berkeley erupted in flames. A brush fire started in Wildcat Canyon, whipped down Codornices Canyon, crossed Cedar, and raced as far down as Shattuck Avenue. It seemed everything north of campus was on fire. The one o’clock classes had barely begun when the Campanile bells began to clang. Jackie remembers,

The hills went up in smoke. I can still smell it—hot, dry September air, tingling and ominous. . . . We wandered, scared and awed as refugees came down to our green campus lawns.

It was very exciting and very sad. The whole hill, you know, was smoking and burning behind them.

Meanwhile, college life resumed for Jackie and Flo. “Nothing, not even the horror of the fire, had any effect on the excitement of being a student at the University,” reports Flo. Jackie decided to get a teaching degree to give her a way to make a living, but she preferred her art classes. She

would lunch on a milkshake and graham crackers, swish her long skirts across campus, or hike with Flo in the hills in their baggy hiking pants and middy blouses. There were big bonfires in the Greek theater; and then, “occasionally” Jackie said, “you studied.”

Jackie contemplated her image and her relationship with Wallen Maybeck:

Dates were very important. I soon learned that if you were pretty you need not do anything—if not, you had to be vivacious and entertaining. I had unthinking good health and a wide smile. I think I was also enterprising, generous, hard-working, romantic, selfish, and lazy. And under all the foam of a new life flowed the deep, steady stream of Wallen’s friendship.

I guess I always knew in my heart I would marry Wallen, right from the time I first met him. But I also felt that I had to have a little experience in the meantime, and also sort of prove to myself that I could attract other men.

Although she returned again and again to dreams of a future with Wallen, Jackie continued to meet her high school beau, Huntington Benson, during vacations at the ranch, achieving “the state of weightlessness . . . by much kissing.” In the summer of 1925, Huntington asked Jackie what she wanted to be. Her reply was prescient: “I said, well, I was going to be a legend.”

In her memoir, Jackie was clear about her reasons for going to UC Berkeley: “I had come to college to get into the world. I mainly learned from those four years of college a way of life. A way of balancing work with pleasure, simplicity with beauty, love with the future.” Her college experience and her growing involvement with the Maybecks furthered her assimilation as a Californian; but she did not disappear into the proverbial American melting pot. A distinctive confidence in herself arose from her Dutch roots, her experience as an immigrant, and her evolution as a liberated, college-educated woman of the 1920s.

The train clopped along tooting through the tunnels and the little towns. . . . Until San Rafael, then suddenly the sharp prick of eucalyptus and a mysterious breath of fog on the skin.

At the University of California, Berkeley, she met Florence Jury, who would become a lifelong friend. When my husband and I knew them in their late seventies, they depended on each other. Both widows, they called each other every morning to talk about plans for the day or breakfast

down the hill on Shattuck Avenue. Flo described meeting Jackie in their freshman year:

Sitting directly across the table from me was a tall, slender girl with curly golden hair and blue eyes the shade of the northern summer sky. Her face was different, not pretty,

but arresting and unforgettable in its planes and contours. It was no time at all before we were smoking an after-dinner cigaret [sic] under the outside stairs. . . . There was so much to talk about.

When Jackie came to Berkeley, the university was already considered one of America’s premier institutions of higher learning. UC Berkeley was on the map and was the heart of the community, much as it is today. The school had been coeducational since 1870, unusual for American universities at the time. California’s (male) voters, however, did not believe that attaining the age of majority was enough to qualify a woman to vote. They defeated a measure to establish female suffrage in 1896. Fifteen years later, just in time for Jackie’s generation, California became the sixth state in the United States to enfranchise women, presaging the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

Having won the right to vote, the modern women of the twenties were exploring and adopting new values. They bobbed their hair, shortened their skirts, drank cocktails, and smoked. They mingled openly with men and burst onto the college scene in larger numbers than ever before. Corsets were swapped in favor of loose-fitting dresses that expressed their carefree spirit.

Jackie “tingled with excitement” as she stood in long lines to sign up for classes. With its mature trees and dirt paths, the campus reminded Jackie of the ranch.

Then near midday on September 17, 1923, Berkeley erupted in flames. A brush fire started in Wildcat Canyon, whipped down Codornices Canyon, crossed Cedar, and raced as far down as Shattuck Avenue. It seemed everything north of campus was on fire. The one o’clock classes had barely begun when the Campanile bells began to clang. Jackie remembers,

The hills went up in smoke. I can still smell it—hot, dry September air, tingling and ominous. . . . We wandered, scared and awed as refugees came down to our green campus lawns.

It was very exciting and very sad. The whole hill, you know, was smoking and burning behind them.

Meanwhile, college life resumed for Jackie and Flo. “Nothing, not even the horror of the fire, had any effect on the excitement of being a student at the University,” reports Flo. Jackie decided to get a teaching degree to give her a way to make a living, but she preferred her art classes. She

would lunch on a milkshake and graham crackers, swish her long skirts across campus, or hike with Flo in the hills in their baggy hiking pants and middy blouses. There were big bonfires in the Greek theater; and then, “occasionally” Jackie said, “you studied.”

Jackie contemplated her image and her relationship with Wallen Maybeck:

Dates were very important. I soon learned that if you were pretty you need not do anything—if not, you had to be vivacious and entertaining. I had unthinking good health and a wide smile. I think I was also enterprising, generous, hard-working, romantic, selfish, and lazy. And under all the foam of a new life flowed the deep, steady stream of Wallen’s friendship.

I guess I always knew in my heart I would marry Wallen, right from the time I first met him. But I also felt that I had to have a little experience in the meantime, and also sort of prove to myself that I could attract other men.

Although she returned again and again to dreams of a future with Wallen, Jackie continued to meet her high school beau, Huntington Benson, during vacations at the ranch, achieving “the state of weightlessness . . . by much kissing.” In the summer of 1925, Huntington asked Jackie what she wanted to be. Her reply was prescient: “I said, well, I was going to be a legend.”

In her memoir, Jackie was clear about her reasons for going to UC Berkeley: “I had come to college to get into the world. I mainly learned from those four years of college a way of life. A way of balancing work with pleasure, simplicity with beauty, love with the future.” Her college experience and her growing involvement with the Maybecks furthered her assimilation as a Californian; but she did not disappear into the proverbial American melting pot. A distinctive confidence in herself arose from her Dutch roots, her experience as an immigrant, and her evolution as a liberated, college-educated woman of the 1920s.

|

Growing up in Sierra Madre, California, Pamela Valois moved north to attend UC Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement. After almost flunking out due to political rallies, she returned to Los Angeles to become a dental hygienist. Then, with a solid part-time job, she became a quasi-hippie, selling macramé and her photos at weekend craft fairs.

Pam got married on the lawn of Jacomena Maybeck’s Berkeley cottage and studied photography with Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco. Her book “Gifts of Age: Portraits and Essays of 32 Remarkable Women,” a bestseller inspired by Jacomena, was published in 1985. After mothering two sons, Pam earned a master’s degree and started a new career in healthcare. At age seventy-five, she’s been retired for ten years and lives in Jacomena’s “High House” with her husband—it’s like a tree house, with redwoods, deer, and skunks as neighbors. Follow Pam on:

|