Essays, Chapbooks, Contests...Etcetera

ANNETTE LIBESKIND BERKOVITS

Author & Poet

Author & Poet

|

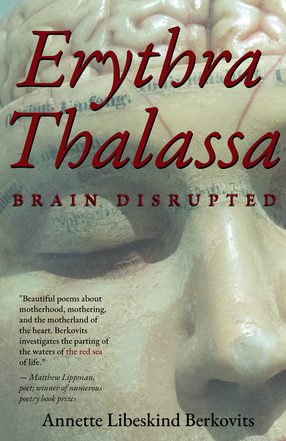

About Erythra Thalassa:

This collection of poems is a searing portrayal of a mother’s anguish over the sudden hemorrhagic stroke of her son - devoted father of two young girls - rendering him a quadriplegic in the prime of his life. An intimate glimpse of a world shattered by stroke, in which each poem not only illuminates, but reimagines life with hope and acceptance. The poems included below have been reprinted with permission from the publisher, Tenth Planet Press. |

|

Small and Monstrous

Meditation 3 Who knew little indignities Could be so monstrous? No one knows until It happens to them. Can’t scratch your nose Can’t turn in bed Can’t rub your eye Can’t put food in your mouth Your brain has rendered your Neck, arms, hands, legs, feet. useless. You lie still as a boulder, helpless like a newborn. Can’t go to the toilet Can’t wipe your butt Can’t dry your snot Can’t push a call button. So go ahead enjoy That scratch, that turn, That wipe, that movement That lets you know you are “normal.” |

Stable

My favorite new word I roll it on my tongue, try it on for size. It fits! It’s perfect. When friends and neighbors approach me, meaning well and ask: how is he? What shall I say? Should I enumerate the myriad tribulations, procedures, medical disasters, surgeries? Perhaps I should tell all about his searing pain, or the utter hopelessness of his condition? He is stable, I say with a smile on my lips, a stone in the pit of my stomach. My mind sees him jumping off the lifeguard’s perch to save a drowning swimmer. |

Annette discusses her chapbook...

As you wrote the poems, was the process healing in any way - did it help you to come to terms with the hurricane of feelings you experienced?

When I wrote “Small and Monstrous” I was hyperaware of the most unremarkable bodily sensations: a need to scratch an itch, to blow my nose, or simply to shift from an uncomfortable position. When we are well, we perform these actions unconsciously and give them no thought. It is only when our body fails us that we appreciate the simple actions that make us feel human and capable of functioning in the world.

Because my son’s condition forced me to face how insurmountable such simple actions can be for a quadriplegic, I became grateful to be able to do these simple, yet essential, things for myself. In that respect, being able to express and record my feelings aided in my healing process. I also hoped that readers might gain an awareness of how lucky they are to be able to do something as simple as being able to push a button to activate a cell phone, TV or a call button for a nurse in the hospital.

The healing component of writing “Stable” was different. Many relatives and friends inquire about my son’s condition when they see me. Of course, they do! Some call regularly. I had been giving them bad news for several years, each time with a growing anxiety on my part that I had disappointed them. After such a long time I imagined them thinking “Surely, he is a bit better, isn’t he?” People crave a feel-good story, an amazing recovery.

The sad truth is that my son’s physical improvement is nonexistent. In fact, his severely contracted limbs are worse. It’s lucky and true that he has made great cognitive progress since the stroke; yet who but the very closest friend would be prepared to listen to the litany of tiny steps forward, barely noticeable but to those who spend the most time with him?

When presented with, “How is Jeremy?” I often had the feeling, if not necessarily the appearance, of a deer in the headlights. What should I say? I didn’t want to bore or disappoint my interlocutors - hence, my “invention” of the response “stable.” It serves to diminish my anxiety when I am approached with well-intentioned inquiries. The ability to give an honest and less discouraging reply is a component of my healing. The very last line of the poem, in which I see my son as a vigorous lifeguard, reminds me each time that “stable” is light-years away from “well.”

What do you hope your readers will take away from this book?

First and foremost, I hope readers will stop to realize that whatever their current state of health, that condition is not a given. It can change at any moment. Somewhere deep in our psyche we realize we might get sick and/or die, but honestly, how many people are aware of this all of the time? Even worse, few of us think that something awful and unimaginable will happen to someone we love. Coming to this realization - not so often as to become depressed - but enough that we remember to CHERISH life and to make sure our loved ones KNOW how we feel about them is one important idea to convey via this book.

Another equally important goal is to convey that life is made of small pleasures that we take for granted until we lose them, such as the ability to stand under an invigorating shower and feel the water cascade over our skin or making ourselves a cup of freshly ground coffee and inhaling its aroma as we sip it from our favorite mug. These kinds of rarely appreciated small joys - the micro moments – are the ones that make our lives worth living.

Lastly, I want to make young people aware that stroke is not something only their parents or grandparents may experience. It is a devastating, life-altering condition that can befall them, especially now with Covid-19. Health precautions should be followed irrespective of one’s age.

As you wrote the poems, was the process healing in any way - did it help you to come to terms with the hurricane of feelings you experienced?

When I wrote “Small and Monstrous” I was hyperaware of the most unremarkable bodily sensations: a need to scratch an itch, to blow my nose, or simply to shift from an uncomfortable position. When we are well, we perform these actions unconsciously and give them no thought. It is only when our body fails us that we appreciate the simple actions that make us feel human and capable of functioning in the world.

Because my son’s condition forced me to face how insurmountable such simple actions can be for a quadriplegic, I became grateful to be able to do these simple, yet essential, things for myself. In that respect, being able to express and record my feelings aided in my healing process. I also hoped that readers might gain an awareness of how lucky they are to be able to do something as simple as being able to push a button to activate a cell phone, TV or a call button for a nurse in the hospital.

The healing component of writing “Stable” was different. Many relatives and friends inquire about my son’s condition when they see me. Of course, they do! Some call regularly. I had been giving them bad news for several years, each time with a growing anxiety on my part that I had disappointed them. After such a long time I imagined them thinking “Surely, he is a bit better, isn’t he?” People crave a feel-good story, an amazing recovery.

The sad truth is that my son’s physical improvement is nonexistent. In fact, his severely contracted limbs are worse. It’s lucky and true that he has made great cognitive progress since the stroke; yet who but the very closest friend would be prepared to listen to the litany of tiny steps forward, barely noticeable but to those who spend the most time with him?

When presented with, “How is Jeremy?” I often had the feeling, if not necessarily the appearance, of a deer in the headlights. What should I say? I didn’t want to bore or disappoint my interlocutors - hence, my “invention” of the response “stable.” It serves to diminish my anxiety when I am approached with well-intentioned inquiries. The ability to give an honest and less discouraging reply is a component of my healing. The very last line of the poem, in which I see my son as a vigorous lifeguard, reminds me each time that “stable” is light-years away from “well.”

What do you hope your readers will take away from this book?

First and foremost, I hope readers will stop to realize that whatever their current state of health, that condition is not a given. It can change at any moment. Somewhere deep in our psyche we realize we might get sick and/or die, but honestly, how many people are aware of this all of the time? Even worse, few of us think that something awful and unimaginable will happen to someone we love. Coming to this realization - not so often as to become depressed - but enough that we remember to CHERISH life and to make sure our loved ones KNOW how we feel about them is one important idea to convey via this book.

Another equally important goal is to convey that life is made of small pleasures that we take for granted until we lose them, such as the ability to stand under an invigorating shower and feel the water cascade over our skin or making ourselves a cup of freshly ground coffee and inhaling its aroma as we sip it from our favorite mug. These kinds of rarely appreciated small joys - the micro moments – are the ones that make our lives worth living.

Lastly, I want to make young people aware that stroke is not something only their parents or grandparents may experience. It is a devastating, life-altering condition that can befall them, especially now with Covid-19. Health precautions should be followed irrespective of one’s age.

|

Scientist, educator, conservationist, and author, Annette Libeskind Berkovits, was born in Kyrgyzstan and grew up in postwar Poland and the fledgling state of Israel before coming to America at age sixteen.

Culminating her three-decade career with the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York as Senior Vice President and recognized by the National Science Foundation for her outstanding leadership in the field, Annette spearheaded the institution’s science education programs throughout the nation and the world. Despite being uprooted from country to country, Annette has channeled her passions into language study and writing. She has published two memoirs, short stories, selected poems, and completed To Swallow the World, a debut historical novel. Her stories and poems have appeared in Silk Road Review: a Literary Crossroads; Persimmon Tree; American Gothic: a New Chamber Opera; Blood & Thunder: Musings on the Art of Medicine; and The Healing Muse and in the Best of Kindness 2020 anthology, an Origami Poems Project. Her first memoir, In the Unlikeliest of Places, a story of her remarkable father’s survival, was published by Wilfrid Laurier University Press in September 2014 and reissued in paperback in 2016. Her second memoir, Confessions of an Accidental Zoo Curator, was published in April 2017. Erythra Thalassa: Brain Disrupted is her first poetry chapbook/memoir about her emotional response to her son’s stroke. |