Fine Art

JAC CARLEY

Artist & Educator

Jac shares the inspiration behind her work on braille and how her background and career in dance has enhanced her fine art projects.

Why braille?

Braille found me. While waiting for an appointment at my borough hall in Berlin in 2019, I rummaged through the book exchange table. Who knows how ten fifty-year-old braille books ended up in that pile? They’d originated from the GDR national library for the blind in Leipzig, the names of the very few borrowers still in the front section.

I’d already been sketching in old books, so this find was quite fortuitous. The books are heavy and large, I only managed to take three of them. And so began the challenge and discovery phase.

Note: Jac shares that braille can be printed at any size.

Braille found me. While waiting for an appointment at my borough hall in Berlin in 2019, I rummaged through the book exchange table. Who knows how ten fifty-year-old braille books ended up in that pile? They’d originated from the GDR national library for the blind in Leipzig, the names of the very few borrowers still in the front section.

I’d already been sketching in old books, so this find was quite fortuitous. The books are heavy and large, I only managed to take three of them. And so began the challenge and discovery phase.

Note: Jac shares that braille can be printed at any size.

Is there anything you'd like to say about working with braille? For instance, is it difficult to work through/around the textured surface to keep the braille intact?

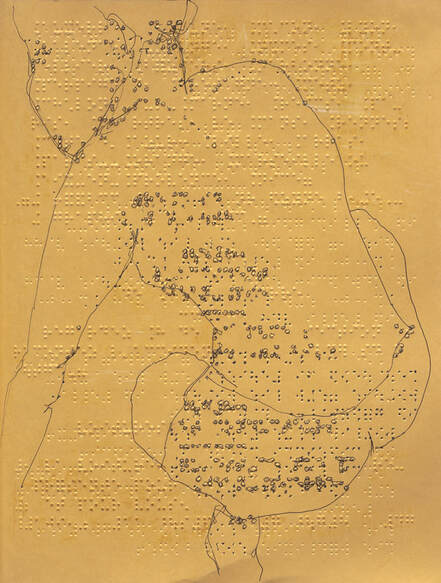

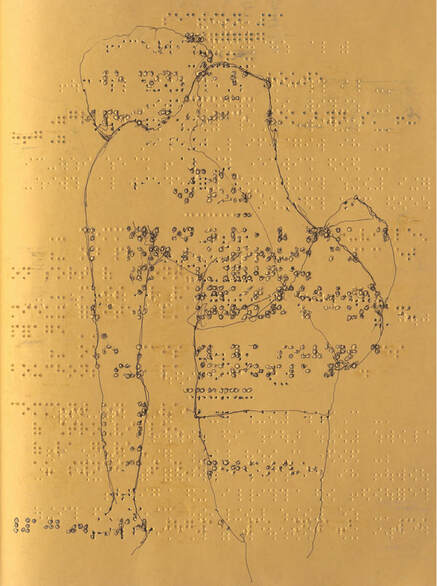

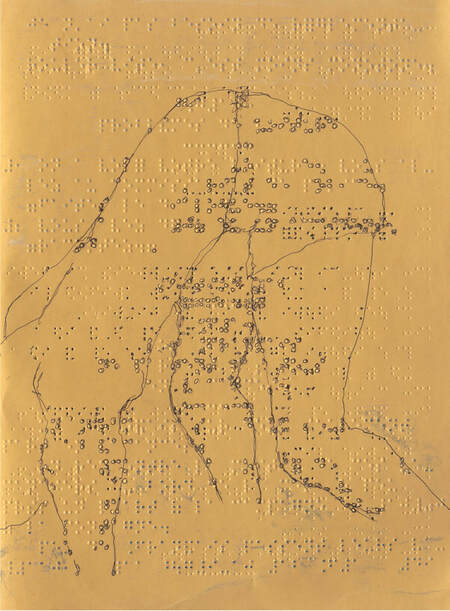

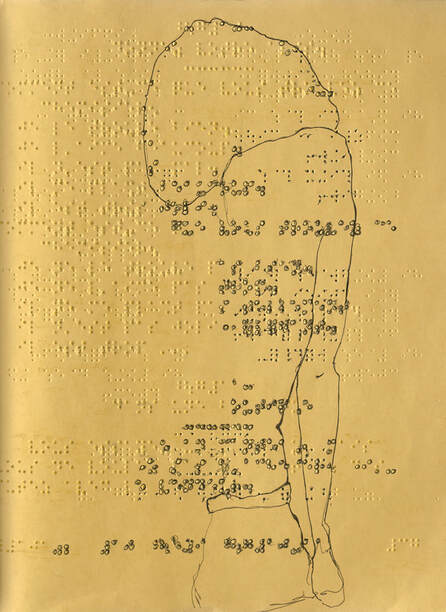

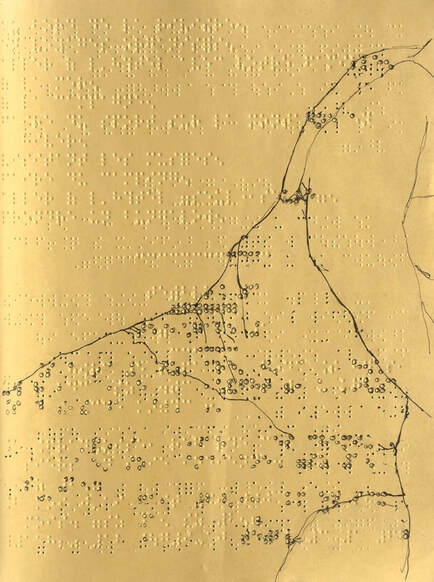

It’s impossible to draw a simple line. The nubs and indentations are like a road filled with potholes and boulders when you’re driving a soft nr 6 pencil.

The nubs that create individual letters are created by a special ‘punching’ typewriter, one designed to raise the paper (from behind), but not puncture it. The paper itself is quite heavy. As both sides of every page are used in a braille book, there are also many indentations on both sides, where the nub emerges on the other side. These can’t be felt. Fingertips can only read the nubs, but between the nubs and indents, my pencil is continually thrown off course during life-drawing sessions. It’s not a graceful or elegant sensation; it’s not possible to do ‘nice’ sketches.

Most of these works are of Irene Graziadei, an Italian musician and performer who posed for Sketch the Moment Berlin twice a week over several years. Her poses were very, very short, a few for five minutes, or she moved in slow motion. There was only enough time to nab the essence of what she was doing with pencil, soft pastel, and/or Graf pigment. I usually turned a new page for each pose, so lots and lots of work emerged – a vigorous two hours for both Irene and the artists. While reworking the sketches at home, I learned just how robust the braille page is. Meant to be read many times by many different hands, my eraser hardly diminished the structure.

It wasn’t until the second braille volume that I reduced the figure to pure line and began circling the nubs and dotting the indentations.

It’s impossible to draw a simple line. The nubs and indentations are like a road filled with potholes and boulders when you’re driving a soft nr 6 pencil.

The nubs that create individual letters are created by a special ‘punching’ typewriter, one designed to raise the paper (from behind), but not puncture it. The paper itself is quite heavy. As both sides of every page are used in a braille book, there are also many indentations on both sides, where the nub emerges on the other side. These can’t be felt. Fingertips can only read the nubs, but between the nubs and indents, my pencil is continually thrown off course during life-drawing sessions. It’s not a graceful or elegant sensation; it’s not possible to do ‘nice’ sketches.

Most of these works are of Irene Graziadei, an Italian musician and performer who posed for Sketch the Moment Berlin twice a week over several years. Her poses were very, very short, a few for five minutes, or she moved in slow motion. There was only enough time to nab the essence of what she was doing with pencil, soft pastel, and/or Graf pigment. I usually turned a new page for each pose, so lots and lots of work emerged – a vigorous two hours for both Irene and the artists. While reworking the sketches at home, I learned just how robust the braille page is. Meant to be read many times by many different hands, my eraser hardly diminished the structure.

It wasn’t until the second braille volume that I reduced the figure to pure line and began circling the nubs and dotting the indentations.

|

Do the highlighted braille letters have any connection to the figure in terms of the meaning of the piece, or is it random - just used for shadowing and texture?

The nubs and the indents present random opportunity for shading, background or other indications. I can’t read braille, not with my fingertips (I beg any sighted person to attempt this!), and I was unable to remember the individual alphabet positions of the nubs well enough to decipher any letters visually. Plus, the nubs are actually hard to see. But once circled or highlighted, the nubs and indents imply words, and they grant the two-dimensional line drawings both depth and volume; moreover, they suggest the context of a hidden inner life. My colleague and mentor, Lara Faroqui, urged me to scan them. Using professional services (Cruse Scan, structural scan system), I commissioned about 10 drawings to be scanned and had a few printed on high quality art paper, as large as the data would allow. 100 x 70 cm (40 x 28 inches) The drawings came to life; the sculptural scanning process produced a far more vivid depiction of the nubs and indents than the actual page does. The brilliancy of the prints, far larger than the book page, stopped me in my tracks. Several were shown at the annual Sketch the Moment group exhibition. Many visitors instinctively reached up and touched the glass. It seemed impossible for many not to touch the art. The images had gained an innate and overt sensuality – two-dimensional works became tactile. |

Leaning Out

Fineliner on Braille (Cruse Scan) © Jacalyn Carley |

For Jac, something deeply personal emerged.

Around this time, Christine Blasey Ford was being interviewed at the 2018 Supreme Court hearing, and this sent me reeling, back into my own horrific rape story. This was a story I had carried intimately – one I had only shared with a few people. Words could never capture the full emotional impact of what I experienced – they would diminish it. I’d shut the story down.

Around this time, Christine Blasey Ford was being interviewed at the 2018 Supreme Court hearing, and this sent me reeling, back into my own horrific rape story. This was a story I had carried intimately – one I had only shared with a few people. Words could never capture the full emotional impact of what I experienced – they would diminish it. I’d shut the story down.

|

Touch.Me.Not.

Installation with Chicken Wire, Leotards & Nails ~ 36 x 12 x 8 inches © Jacalyn Carley |

Then, forty years later, my engagement with braille suddenly made sense. The work spoke directly to that event: my drawings captured lively figures, almost always alone, nude and vulnerable. The figures are strong but enigmatic – all trapped on a page full of a story that no one can read with naked eyes. Everyone wants to touch them. What could be worse than touching a hurt woman, than touching the art? Yet it is exactly that: the unreadable and unspeakable stories that give my figures on braille both volume and depth.

At this point, I stopped drawing to reflect on my own story and what it could mean for a new direction with my art. As an autodidact, the idea of not making art was frightening. The result: an installation with sculpture, text, found objects, mutilated photographs, and also the original braille images, titled ‘Touch.Me.Not.’ It was held at the Berlin Art Institute, where I was fortunate enough to have a residency for several months. Have you spoken with any blind people about your work? If yes, what is their reaction to your work? Unfortunately, I have not. I have since learned that reading braille is no longer popular or practiced as much as you would think. The virtual/internet/auditory world has reduced the need for such tedious reading, just as it has for reading in general. |

|

Are the installation braille pieces meant to be touched? I'm sure viewers have asked. They have that pull.

While reflecting on the braille scans, I spent much of that time writing and thinking about touch. We all want to be touched, to have our stories touch other people. Through touch we express love and acceptance in a way that words cannot. But for women who have suffered sexual abuse, rape and other trauma, touch triggers memories. How can one heal and recover through love and acceptance when this same mechanism lets the devils out of the box? The tool for moving on is the same one that triggers shame, anger, pain. Try going through all that on a romantic evening with a new and loving, partner. How does your knowledge of dance and movement enhance your figurative work? Has dance inspired your fine art projects in other ways? I am always moving, deeply connected to my body through somatic practice and yoga. The last several years I’ve been creating Action artwork, using very large 1 x 10 m (3’3” x 32’10”) rolls of 300g paper, whacking and dancing with lavender dipped in ink. Lavender represents peace, inner calm and abundance to me – it smells amazing and makes me very happy to do physical artwork. Recently, my first corporate sale was a large Action work for new offices of Frau Tonis Parfum, exclusive fragrances manufactured in Berlin. More on the Touch.Me.Not. series in this video montage. |

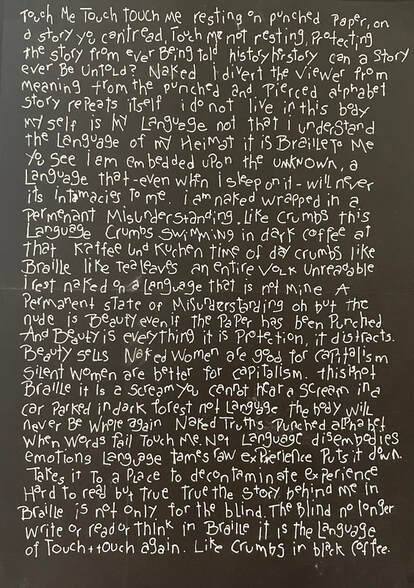

The Story

White Marker on Black Paper ~ 16 x 12 inches © Jacalyn Carley |

Where do you find sanctuary?

It’s the place where I search for the tangent between doing art and finding the inner calmness to hear myself, like an inner crossroads that seems to always be somewhere else on the map. I’ve come to accept frustration and inner drive as furniture in my sanctuary. I don’t believe in complacency – too much quietude, and tinnitus takes over. Who needs that?

It’s the place where I search for the tangent between doing art and finding the inner calmness to hear myself, like an inner crossroads that seems to always be somewhere else on the map. I’ve come to accept frustration and inner drive as furniture in my sanctuary. I don’t believe in complacency – too much quietude, and tinnitus takes over. Who needs that?

|

Jac Carley

Follow Jac on:

|

Jac Carley is a Berlin-based artist and educator. After graduating from George Washington University with a degree in modern dance education in the mid-1970s, she moved to Berlin and cofounded ‘Tanzfabrik Berlin.’ In her career as choreographer, her evening-length works helped define the early modern dance scene in a divided West Berlin and toured throughout Europe and the U.S. for two decades with support of the Berlin Ministry of Arts and Goethe Institute.

Jac choreographed to avant-garde literature instead of with music, using texts by authors like Kurt Schwitters, Gertrude Stein, Raymond Federman, Ernst Jandl. Writing is also part of her artistic practice. Aside from numerous poetry publications, she has authored two fiction and two nonfiction books (all in German translation: Fischer, Henschel and Eichborn Verlagen). For the last ten years, Jac has focused on visual arts practice and teaching. Her primary interest is the female figure and women’s stories, capturing the sensual. She incorporates text and implied stories in her artworks, often drawing in old books found at flea markets. Her drawings, prints, and photography have been shown in numerous exhibitions and venues in Berlin and Venice. Jac was the on-site director for Sarah Lawrence’s ‘Summer Arts in Berlin’ study abroad program from 2010–2020. In spring 2022, she taught ‘Dance and Community Building: Looking at Utopias’ for Bard College Berlin (with Professor Ingo Reulecke). |