Fine Art

JILL CLIFFER BARATTA

Fine Artist & Educator

Jill with her Piece "Cascade 4"

Photo Courtesy: Jill Baratta

Photo Courtesy: Jill Baratta

Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor, spoke with Jill about her journey in the arts and her experiences as an educator and art therapist.

|

Your work is very diverse. How have your inspirations and processes changed during your artistic journey?

My work is diverse, in part, because of my experiences as an educator. My feeling is that, when you’re working with students, you meet them where they are, and you provide a lot of options to help each artist find their own journey. I suppose my work is also diverse due to working in short spurts while raising three children – the on-task time was broken up due to family responsibilities. I've been inspired by my family in subject matter at times (photo transfers, baseball themed work, drawings, and prints), and my students at other times (my layered linocuts). At times, I created from my personal need to express a certain feeling (Visual Journal and Adulation series). My processes have changed from my roots in watercolor to the desire to incorporate photography - by way of photo transfer. The latter led me to printmaking, where I studied with two of our illustrious NAWA members, Penny Dell and Dorothy Cochran. My current role as executive director of NAWA has me working sporadically again – printmaking, drawing, collage, and experimenting with photo transfers. |

Jill's Baseball Series Inspired by her Sons' Involvement in Baseball

|

Jill also studied dance and explains how this training taught her to push the envelope artistically.

When I first came to New York, the Grand Union dance group was performing their last dance concert, and the whole evening was about these dancers in a class copying the teacher. It was very humorous and ironic. It was about how stifling this could be [simply copying what another artist is doing]. Your muscle memory – as a dancer in particular – is your body going to that place that’s familiar. I was studying dance technique at NYU. I had teachers there who taught classes that were very eclectic and demonstrated how to handle the material in such a way that you push the envelope. This blew apart my compositional acuity.

When I switched back to art and began teaching, I focused on providing the skills while simultaneously teaching the ability to push that envelope.

When I first came to New York, the Grand Union dance group was performing their last dance concert, and the whole evening was about these dancers in a class copying the teacher. It was very humorous and ironic. It was about how stifling this could be [simply copying what another artist is doing]. Your muscle memory – as a dancer in particular – is your body going to that place that’s familiar. I was studying dance technique at NYU. I had teachers there who taught classes that were very eclectic and demonstrated how to handle the material in such a way that you push the envelope. This blew apart my compositional acuity.

When I switched back to art and began teaching, I focused on providing the skills while simultaneously teaching the ability to push that envelope.

|

|

Do you stick with a theme long-term? I do not have a long-term theme, which does not make my work commercially marketable. It’s not recognizable with a particular theme or style. I am not greatly concerned about this – my emphasis is on authenticity and on facilitating for others. When I feel I must create, I embrace a theme until I feel I have exhausted its meaning. Then, I move on or look for inspiration either inside or outside my studio. When I was teaching watercolor to middle school students, we took a field trip to The Met. We were sketching with them in the American wing where all the statues are in the big atrium. I had done a line drawing of a headless, armless statue as an example. I thought this is iconic, and I expanded on that which became my Adulation series. It’s about idealizing the body in a renaissance kind of manner. |

Do you enjoy the surprises you stumble on while working with a new medium? Have you ever used a “mistake” and made it your own – perhaps, even continuing with what you initially thought to be a mistake and incorporating it elsewhere?

Of course, I enjoy surprises! Long ago, I was taught, and learned through process, that training and preconception are only as valuable as one's ability to let go of either or both. Like in good jazz, there is thematic material – concept or image – and there is improvisation on the theme. This is one reason I love printmaking, because you can infinitely vary the way you execute the same plate or block.

Of course, I enjoy surprises! Long ago, I was taught, and learned through process, that training and preconception are only as valuable as one's ability to let go of either or both. Like in good jazz, there is thematic material – concept or image – and there is improvisation on the theme. This is one reason I love printmaking, because you can infinitely vary the way you execute the same plate or block.

|

But to answer your question…I have used errors to push forward if something was not irretrievable in some way – water-soluble pen, stopping a print before adding layers, printing upside down and finding value in it, photo transfer that mushed, etc. But sometimes you just rip it up and throw it out.

One time I did a watercolor, and I thought I was working with a permanent marker, but it was water soluble. So, when I went in to add color, all the pen marks bled, but the result was exquisite. As I worked, I took control of where I left it alone and where I let it bleed. The bleeding gave it a whole new loose approach that was very beautiful. It became another tool. I incorporated this bleeding edge in other pieces. I have another example in printmaking. Sometimes you’re doing a layered print and by accident you put a plate in upside down. So, you get the image in the wrong orientation as compared to the other layers. This happened with one of the works in my Omen series. There are pieces up in the sky – this was the water originally – and it was a complete accident in the beginning. I decided to give it agency and ran with it. I put it in a couple of shows, and people responded nicely to it. |

Jill's Omen Series - Omen 2 is the "Mistake" Turned Beautiful

|

|

Visitors' Dugout Original and Open Spaces Versions

|

Another time I took a photo of a visitors' dugout from behind at one of my son’s baseball games. It was backlit, and I decided to do this in a print because the photograph came out beautifully. It had all of these complicated layers. The final result was good. But in the process of doing this, and before I put in the dugout, I had a layer with the ground and some trees in the background with an empty space where the dugout was supposed to go. People in this printmaking class thought it was beautiful on its own. So, I did another whole group without the dugout, and it became a study on open spaces. How has your background in graphics design influenced your fine art? Former graphic artists and designers fall very naturally into printmaking. Graphic design is pretty much, by definition, commercial. However, at least when it comes to classic (pre-digital) processes, the techniques required for commercial printing, and those used for fine art printmaking, are closely related. Understanding color layering and separation is key, and the planning aspect takes experience that differs from direct painting. For example, the image must be reversed on a plate, so you have to create a mirrored image of what you want. |

That sounds like a difficult thing to do.

It’s much more natural for someone who has experience in graphic design. Also, as a dancer, you learn to do things from both sides, and you’re also looking in a mirror all the time. One thing that makes it easier today is that you can take a photo of your artwork and put it into your computer and flip it. And then you print it out and make your plate from that. But you still have to have the ability to think [about the reversed image] to plan properly.

Also, colors may be mixed through overlapping images on a page as opposed to mixing paint on a palette. Evolving and adapting graphic techniques to fine art is a natural progression that means engaging the push to creation for the sake of exploration. This is not exclusive to fine art – illustrators and designers do it all the time. However, it is about the intent and purpose of engaging in the process – and I always want to know what the goal is.

It’s much more natural for someone who has experience in graphic design. Also, as a dancer, you learn to do things from both sides, and you’re also looking in a mirror all the time. One thing that makes it easier today is that you can take a photo of your artwork and put it into your computer and flip it. And then you print it out and make your plate from that. But you still have to have the ability to think [about the reversed image] to plan properly.

Also, colors may be mixed through overlapping images on a page as opposed to mixing paint on a palette. Evolving and adapting graphic techniques to fine art is a natural progression that means engaging the push to creation for the sake of exploration. This is not exclusive to fine art – illustrators and designers do it all the time. However, it is about the intent and purpose of engaging in the process – and I always want to know what the goal is.

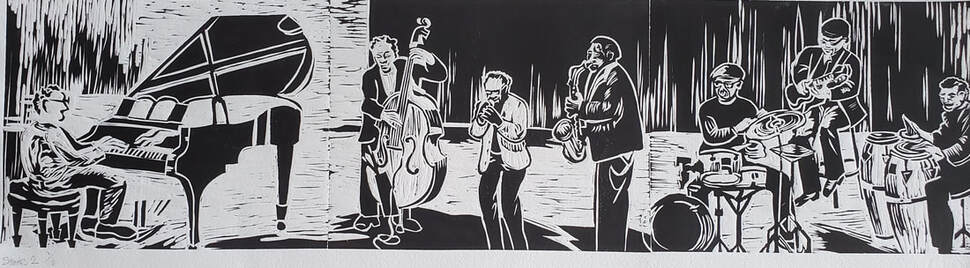

Ensemble 1

Linocut Print ~ 15.5 x 36 inches (Unframed)

© Jill Cliffer Baratta

Linocut Print ~ 15.5 x 36 inches (Unframed)

© Jill Cliffer Baratta

|

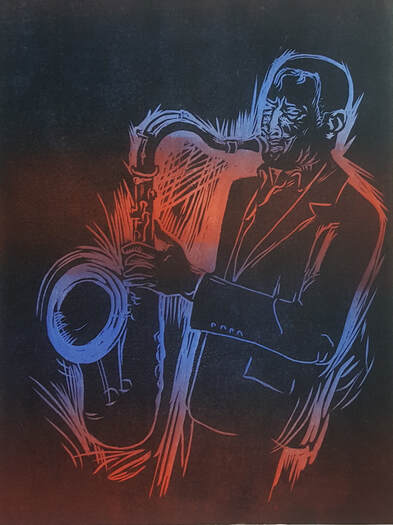

Horn Player

Oil on Canvas ~ 13 x 17 inches © Jill Cliffer Baratta |

A musician’s passion exudes from ever-changing facial expressions while playing. Is this one of the things that inspires you to create fine art in celebration of music?

Absolutely. I call them ‘magicians.’ I have had the privilege to hear and observe some of the finest jazz musicians in the world. What happens when they elaborate in a solo or interact with each other is almost impossible to capture in a frozen image. As you mention, the passion exudes from the musicians’ faces and physical presence, telling us of their immersion in what they do. I try to show this. The work becomes a gestural visualization of the sound, the music, as if I am a human oscilloscope with my tools – a brush, a scribe, a carving tool. |

Ensemble 8

Intaglio with Chine Colle, Ink ~ 18 x 22 inches (Unframed) © Jill Cliffer Baratta Note: Ensemble 8 was used for the cover artwork for Richard Baratta's album Music in Film: The Sequel |

|

When did you develop an appreciation and passion for printmaking? Is there a type of printmaking that you enjoy most?

For a fine art printmaker, at least for me, sometimes it’s about making multiples. It’s about theme and variation. You can print the same thing in a variety of colors. I might start with yellow and then add red, for instance. I already spoke a little about beginning printmaking by way of photo transfer. This began with Polaroid transfers. I liked the look of them. Then, I took a solarplate etching workshop with Dan Welden. I loved the early iteration of this technique, but I later found the plates too tricky. Maybe it was me, but I didn't find the results consistently good. There are a lot of variables. I'd rather do a drypoint etching than fight with all of those variables. As far as what I enjoy most, it would have to be linocut or woodcut printing. I also love the intaglio process – but if I do this, I just do a drypoint, which is to scratch the design onto metal or plexiglass. [Find an article in Britannica about printmaking processes/types.] |

Walter 4

Linocut ~ 22 x 15 inches (Unframed) © Jill Cliffer Baratta |

|

You also studied art therapy. Would you like to share something that particularly moved you?

This story happened during my internship at Hackensack Hospital when I worked with the three children of a leukemia patient. My supervisor understood that this assignment would have value for me personally. My father passed away from leukemia when I was just turning 12, and this experience helped me contextualize the anger and grief I grew up having because I never knew what was really going on with my father – I was furious as a teenager. The children’s father [the leukemia patient] didn’t want the mother to mention cancer. So, we couldn’t talk specifically about what was going on – which was what had happened with me as a child. One day, the five-year-old girl asked if they could draw desert islands. So, the next week, they all did drawings of desert islands. The middle child drew himself in the water crying for help. The little girl had herself and a friend on the island holding black roses. They took these drawings home, and I never saw the children again, even though I contacted their mother explaining my desire to work with them. As a child, you feel what is going on, and your imagination is much worse than what the truth might actually be. This experience allowed me to understand my mother’s position. It helped me put things in perspective. |

Good Eye

Encaustic with Assemblage ~ 26 x 28 x 5 inches © Jill Cliffer Baratta |

As the current executive director of the National Association of Women Artists, what do you find members struggle with the most?

The biggest obstacle for all of us, both members and administration, is dealing with ever-changing technology and how much we are obligated to use and conform to it. The world of computers, programs, platforms and social media moves so fast! As a deeply entrenched association and business, we all need to challenge ourselves to keep up. We are working on a sort of index to help the members know more easily where to find what.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I am a devoted bath-taker. Whenever possible, I like a good daily soak. I decompress by doing puzzles – Sudoku, crossword, and solitaire on my phone. I have practiced Buddhist chanting for forty years now. I find the meditation and philosophy of the Lotus Sutra, which emphasizes cause and effect and the interrelation of all phenomena, helps to keep me grounded in the necessity of fusing wisdom and objective reality. This all gives me peace and allows me to acknowledge, with humility, that I cannot be perfect but will always strive to do my best and learn from errors and obstacles.

The biggest obstacle for all of us, both members and administration, is dealing with ever-changing technology and how much we are obligated to use and conform to it. The world of computers, programs, platforms and social media moves so fast! As a deeply entrenched association and business, we all need to challenge ourselves to keep up. We are working on a sort of index to help the members know more easily where to find what.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I am a devoted bath-taker. Whenever possible, I like a good daily soak. I decompress by doing puzzles – Sudoku, crossword, and solitaire on my phone. I have practiced Buddhist chanting for forty years now. I find the meditation and philosophy of the Lotus Sutra, which emphasizes cause and effect and the interrelation of all phenomena, helps to keep me grounded in the necessity of fusing wisdom and objective reality. This all gives me peace and allows me to acknowledge, with humility, that I cannot be perfect but will always strive to do my best and learn from errors and obstacles.

Jill Cliffer Baratta, MFA, NAWA, is a printmaker/work on paper artist, and currently the Executive Director of the National Association of Women Artists, Inc. Her work has evolved from academic studies at a young age, to employment as a graphic designer/artist, to a fine artist focused on watercolor, printmaking, and collage works on paper.

Focusing on facilitating art for others, her work has varied in style and format. She has created series on baseball, music, and other ranging themes, including her Omen series, and Adulation series, using printmaking techniques of linocut, woodcut, intaglio, photo transfer, and layered combinations. Mentors include Dorothy Cochran, Denise Collins, Basil King, Penny Dell, Christine Ferreira, and Tom Pollock.

Jill’s experiences as an educator are numerous. She developed and taught art classes for students from ages 8 to adult at The Art School at Old Church (TASOC) in Demarest, NJ, including “Art from Our Hearts,” a grant-supported class using art as coping. From 2015 through 2019, she worked at Englewood Hospital, facilitating art activities with out-patient infusion patients and for three years with MarbleJam Kids, utilizing creative arts therapies for autistic children. In 2003, she completed a nine-month internship at Hackensack University Medical Center, doing art therapy with pediatric patients. She also served as artist-in-residence at Tenafly Middle School for 14 years, teaching watercolor painting to gifted middle school students.

Jill studied art at The School of Visual Arts in New York, NY, Grand Valley State University in Allendale, MI, The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, The Art Institute of Chicago, and at local art centers. She studied art therapy at The College of New Rochelle and dance at New York University Tisch School of the Arts, where she received an MFA.

Focusing on facilitating art for others, her work has varied in style and format. She has created series on baseball, music, and other ranging themes, including her Omen series, and Adulation series, using printmaking techniques of linocut, woodcut, intaglio, photo transfer, and layered combinations. Mentors include Dorothy Cochran, Denise Collins, Basil King, Penny Dell, Christine Ferreira, and Tom Pollock.

Jill’s experiences as an educator are numerous. She developed and taught art classes for students from ages 8 to adult at The Art School at Old Church (TASOC) in Demarest, NJ, including “Art from Our Hearts,” a grant-supported class using art as coping. From 2015 through 2019, she worked at Englewood Hospital, facilitating art activities with out-patient infusion patients and for three years with MarbleJam Kids, utilizing creative arts therapies for autistic children. In 2003, she completed a nine-month internship at Hackensack University Medical Center, doing art therapy with pediatric patients. She also served as artist-in-residence at Tenafly Middle School for 14 years, teaching watercolor painting to gifted middle school students.

Jill studied art at The School of Visual Arts in New York, NY, Grand Valley State University in Allendale, MI, The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, The Art Institute of Chicago, and at local art centers. She studied art therapy at The College of New Rochelle and dance at New York University Tisch School of the Arts, where she received an MFA.

|