Play & Book Excerpts

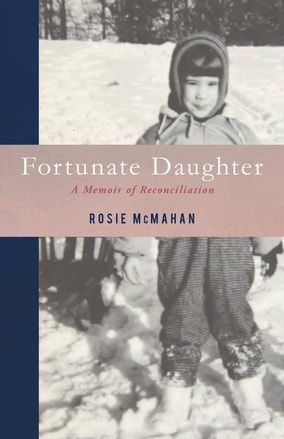

Fortunate Daughter:

A Memoir of Reconciliation

(She Writes Press)

© 2021 Rosie McMahan

"I was twelve years old when I met Ella, the first person who helped me—truly helped my whole family—not feel lost and done for. Anna found her. Apparently, she got her name from a woman at an Alateen meeting we’d been attending in the basement of St. Clement Church. Ella worked alongside Dr. Yaffe, a psychiatrist who would soon become renowned for her work in post-traumatic stress disorder. These two self-defined feminists provided individual and group counseling at the Women’s Mental Health Collective.

The night before we left for our first appointment, I wrote in my journal:

Why did Anna have to tell anyone? How could she? I’ll go, but I’m not going to say anything. No one can make me say a word if I don’t want to. Daddy thinks it’s a joke otherwise he wouldn’t allow us to go. I’m not going to go along with him anymore! Not here at home. Not anywhere. Anna is such a fool to think she can do anything to stop him! I hate him! I hate how controlling he is. I hate how Mommy can’t do a thing about him.

After school the next day, Mom brought us to Ella and Dr. Yaffe’s office. How she had the wherewithal to arrange these appointments and yet couldn’t do more to make our home safe, I will never understand. I also don’t really know how Dad, with his incessant need to control our lives, permitted us to talk with these women, so obviously a threat to his reign. Maybe it was because all the earlier efforts to get outside help had fallen flat.

My siblings and I filed in, first Peter in his wheelchair, then me, then Anna and Christina, bringing up the rear position. We did that a lot—fall into our birth order without planning it. It would just happen.

“Welcome, sit where you’d like,” a woman with curly brown hair and glasses said to us. The other woman looked kind of like the witch from the Wizard of Oz, but I could tell right away she wasn’t as mean or scary because of her eyes, gentle and seeing. She stood close to the woman with curly hair, their shoulders touching, and extended her hand, like we were grownups or something.

“I’m Dr. Yaffe, and this is Ella,” she said, and they both sat down, Dr. Yaffe gesturing with her hand that we should do the same.

Peter maneuvered his wheelchair into a spot, and my sisters and I just stood there, waiting to be told what to do next.

“You can have a seat,” Ella said. “Your parents gave us permission to talk with you. We understand that your family wants help.” Pause. “We want to help.” And then they looked at each other—not at us—as if to remind themselves or remember. I don’t know.

“I need to use the bathroom,” Christina said, and Anna and I rolled our eyes in unison.

“Sure,” Ella said, and got up to show her where it was. We sat quietly, Peter and Anna and I, looking at the carpet.

“Can I have a piece of paper?” I asked.

“Certainly.” Dr. Yaffe moved to tear a piece from the notepad on her lap. Her ankles were thin like willow branches, and I imagined what she’d look like walking in water with bare feet.

“I don’t need a big piece, just something my brother can fold. He likes to fold.”

“What do you make?” she asked Peter, handing him a piece of torn notebook paper.

“He doesn’t make anything,” I said. “He just likes folding.”

My sisters and I sat on the soft, large couch, our knees touching. I felt enveloped by worn and textured corduroy. Cocooned within the warmth, my breath deepened, and my eyelids closed, as my sisters simultaneously raced to answer Ella and Dr. Yaffe’s questions.

“So, you’re telling me that even though he hits everyone in the family, it’s mostly you, Anna, whom he goes after the most?” Dr. Yaffe asked.

“Uh-uh,” Christina said. “He hits Mommy the most of all.”

“She’s asking us about what Daddy does to us kids,” Anna clarified. “I caught him looking through the keyhole when I was opening the bathroom door. He got a big egg on his head.”

I pretended to listen, so as not to alert anyone to the ringing in my ears, the ringing that blocked out everything and separated me from the “what” that was going on outside of me, the ringing that prompted me to realize something was happening that made me feel like my life as I knew it was over, that I was going to die, at least the “I” that existed before the sound.

In any case, Ella and Dr. Yaffe made recommendations for the course of therapy they thought would work best for our family. My sisters and I now were now required to see Ella separately. I wouldn’t be able to sleep through one-on-ones.

I wrote in my diary:

Will Ella help me? Is it possible to be honest with someone and have it lead to good? What might Ella accomplish that no one else has? Does she have that kind of power? Do I have the patience? Maybe I should have prayed more. Isn’t that what Esther wondered. I’d rather be with her now in Siberia. With Esther from the Endless Steppe.

The night before we left for our first appointment, I wrote in my journal:

Why did Anna have to tell anyone? How could she? I’ll go, but I’m not going to say anything. No one can make me say a word if I don’t want to. Daddy thinks it’s a joke otherwise he wouldn’t allow us to go. I’m not going to go along with him anymore! Not here at home. Not anywhere. Anna is such a fool to think she can do anything to stop him! I hate him! I hate how controlling he is. I hate how Mommy can’t do a thing about him.

After school the next day, Mom brought us to Ella and Dr. Yaffe’s office. How she had the wherewithal to arrange these appointments and yet couldn’t do more to make our home safe, I will never understand. I also don’t really know how Dad, with his incessant need to control our lives, permitted us to talk with these women, so obviously a threat to his reign. Maybe it was because all the earlier efforts to get outside help had fallen flat.

My siblings and I filed in, first Peter in his wheelchair, then me, then Anna and Christina, bringing up the rear position. We did that a lot—fall into our birth order without planning it. It would just happen.

“Welcome, sit where you’d like,” a woman with curly brown hair and glasses said to us. The other woman looked kind of like the witch from the Wizard of Oz, but I could tell right away she wasn’t as mean or scary because of her eyes, gentle and seeing. She stood close to the woman with curly hair, their shoulders touching, and extended her hand, like we were grownups or something.

“I’m Dr. Yaffe, and this is Ella,” she said, and they both sat down, Dr. Yaffe gesturing with her hand that we should do the same.

Peter maneuvered his wheelchair into a spot, and my sisters and I just stood there, waiting to be told what to do next.

“You can have a seat,” Ella said. “Your parents gave us permission to talk with you. We understand that your family wants help.” Pause. “We want to help.” And then they looked at each other—not at us—as if to remind themselves or remember. I don’t know.

“I need to use the bathroom,” Christina said, and Anna and I rolled our eyes in unison.

“Sure,” Ella said, and got up to show her where it was. We sat quietly, Peter and Anna and I, looking at the carpet.

“Can I have a piece of paper?” I asked.

“Certainly.” Dr. Yaffe moved to tear a piece from the notepad on her lap. Her ankles were thin like willow branches, and I imagined what she’d look like walking in water with bare feet.

“I don’t need a big piece, just something my brother can fold. He likes to fold.”

“What do you make?” she asked Peter, handing him a piece of torn notebook paper.

“He doesn’t make anything,” I said. “He just likes folding.”

My sisters and I sat on the soft, large couch, our knees touching. I felt enveloped by worn and textured corduroy. Cocooned within the warmth, my breath deepened, and my eyelids closed, as my sisters simultaneously raced to answer Ella and Dr. Yaffe’s questions.

“So, you’re telling me that even though he hits everyone in the family, it’s mostly you, Anna, whom he goes after the most?” Dr. Yaffe asked.

“Uh-uh,” Christina said. “He hits Mommy the most of all.”

“She’s asking us about what Daddy does to us kids,” Anna clarified. “I caught him looking through the keyhole when I was opening the bathroom door. He got a big egg on his head.”

I pretended to listen, so as not to alert anyone to the ringing in my ears, the ringing that blocked out everything and separated me from the “what” that was going on outside of me, the ringing that prompted me to realize something was happening that made me feel like my life as I knew it was over, that I was going to die, at least the “I” that existed before the sound.

In any case, Ella and Dr. Yaffe made recommendations for the course of therapy they thought would work best for our family. My sisters and I now were now required to see Ella separately. I wouldn’t be able to sleep through one-on-ones.

I wrote in my diary:

Will Ella help me? Is it possible to be honest with someone and have it lead to good? What might Ella accomplish that no one else has? Does she have that kind of power? Do I have the patience? Maybe I should have prayed more. Isn’t that what Esther wondered. I’d rather be with her now in Siberia. With Esther from the Endless Steppe.

|

Rosie McMahan was brought up in Somerville, MA at a time when kids and dogs roamed the streets in unlawful packs, and the walk to a barroom or a Catholic church was less than a quarter of a mile away in any direction. She and her husband moved to western Massachusetts in 2001 to raise their children, now 23 and 18 years old.

Her writing has received prizes and she can be heard reading in local venues, including Pecha Kucha (a local storytelling event), the annual Garlic & Arts Festival, and the Greenfield Annual Word Festival (GAWF). In October 2017, she was one of the featured writers in "The Gallery of Readers'' series held at Smith College each year. In 2018, her writing was presented in a juried exhibition titled "COLLABORATION" held at the Burnett Gallery in Amherst, MA. She has also been published in several journals, including Silkworm, Typehouse Literary Magazine, Black Fox Literary Magazine, the 2017 Gallery of Readers Anthology, and Passager Journal. |