Play & Book Excerpts

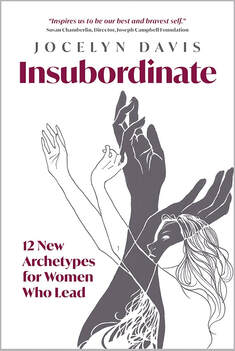

Insubordinate:

12 New Archetypes for Women Who Lead

(Amplify Publishing)

© Jocelyn Davis

Click Book Cover to Pre-order now. Release date is March 21, 2023.

Jocelyn will be joining Myrna Haskell as a guest on Sanctuary's Coffee & Conversation Show in May '23. Stay tuned...

The archetypes addressed in Jocelyn Davis' book are timeless in that they have been around for millennia,

but new in that no one until now has identified them, arranged them thus, and showed how they can inspire women leaders.

The archetypes addressed in Jocelyn Davis' book are timeless in that they have been around for millennia,

but new in that no one until now has identified them, arranged them thus, and showed how they can inspire women leaders.

Three Ways the Archetypes Empower Us

They help us appreciate our strengths. If you took the quiz at the start of this book, you already know the two or three archetypes where you’re most at home. Knowing our home archetypes is one way to appreciate and build on our strengths. Typically, they’ll be clustered in one area of the wheel. My own home types are in the airy northern zone: Escapist, Snow Queen, and Empress. It’s good to know that the roles in which I naturally shine aren’t mere personality tics, but potential sources of power and routes to success.

A friend and I still laugh about something he confessed to me once after a couple of drinks: “When I first met you,” he said, “I thought you were uptight and unfriendly.” He felt bad about letting that slip! But he was right: I am uptight and unfriendly. It’s the Snow Queen in me—the introvert who stands aloof, relying on her frosty intellect to solve problems. When I think about it that way, I give myself permission to be myself. Like Elsa in Frozen, I can “let it go.” I am Snow Queen! Marvel at my ice palaces!

They help us appreciate the strengths of other women. It’s easy to observe someone acting in a way we wouldn’t and dismiss her with a nasty epithet: “Skank.” “Bitch.” “Snob.” When we keep the archetypes in mind, we can move past that initial, shallow reaction (a Medusa’s reaction, by the way) to ask a better question: “Which archetype is she representing?” I don’t mean to suggest we take women’s goodness on faith; there are plenty of toxic women around, just as there are plenty of toxic men, and not all female behavior is well-intentioned. What I do suggest is that we give the woman whose behavior seems alien a second look and ask ourselves not what’s wrong with her, but what we might learn from her.

Caroline, my former colleague whose story appears in chapter 1, was a classic Temptress, her fishnet stockings and flirtatious manner earning her more than a few side-eyes from the women at our company. Caroline went on to become a much-admired CEO, an award-winning entrepreneur, and a columnist for a major newspaper. I now realize I spent too much energy side-eyeing, not enough energy watching and learning.

They help us stretch beyond our comfort zone. Even if we find multiple archetypes congenial, there will always be some we find less so, and it’s these, the ones we tend to suppress, that represent our opportunities for growth. Not that the leadership thinkers who tell us to play to our strengths are wrong; as I’ve said, it’s no use trying to turn ourselves into something we’re not. Playing to strengths, however, is a strategy more applicable to men than to women. Men, remember, can afford to be one-dimensional: they can set their sights on a goal, marshal their resources as tinker, tailor, soldier, or spy, and count on their unique skills to carry them through. James Bond never has to be Dirty Harry for the weekend. Samwell Tarly never has to be Jon Snow. We women, on the other hand, don’t have the luxury to operate in one dimension. And why would we even try? Sure, we have particular talents and should make the most of them, but the real key to our success is our range, wider than any man’s. For us, an expansion of repertoire holds more promise than reprisals of our greatest role.

And if we seek it, we’ll likely find the “new” repertoire right there within us. I agree with Tony Binns, a freelance screenwriter who posted this on Facebook:

The hero’s journey fantasy for men is always starting at the bottom and coming into your own, so you are the complete badass at the end. The hero’s journey fantasy

for women is to be acknowledged for the power they already possess.

This has real-world echoes. Men have been told to roll up shirt-sleeves and work their way to the top, whereas women are struggling to be heard, to not be

interrupted, to be taken seriously, to not have their ideas stolen, and to have equal pay and opportunity as their male counterparts. Men fight for position; women

fight for recognition.

***

Woman is born free, yet everywhere she is in chains: chains of discrimination, violence, abuse, limitation, trauma, self-doubt, self-absorption, fear, anger, shame.

The good news: by breaking big, we may break the chains.

There’s a natural progression for women seeking personal or professional growth: a “developmental model,” as my colleagues in the learning industry used to say. We start out attached to one or two archetypes, operating snugly in our comfort zone. When we find ourselves in situations where our favorite patterns don’t work, we’re apt to fall into the Medusa Trap, directing disdain toward men and even more toward other women. In this effort to puff ourselves up, we may reach for new models and, lacking a full understanding, latch onto their superficial aspects: the domineering Empress, the mocking Jesteress, the timid Escapist. These dress-up games only keep us small and weak, but when we grasp the deep truth of each archetype, reclaiming it from stereotype and building it up from within, we rise tall and mighty.

At the end of this book, having spent time with each archetype, we’ll look to one of the world’s oldest, most popular fairy tales for an example of a woman who masters the entire wheel of fire, earth, water, and air. When we can do the same, not because we have to but because we choose to, then we’ll have accomplished our heroine’s journey—and be insubordinate.

A friend and I still laugh about something he confessed to me once after a couple of drinks: “When I first met you,” he said, “I thought you were uptight and unfriendly.” He felt bad about letting that slip! But he was right: I am uptight and unfriendly. It’s the Snow Queen in me—the introvert who stands aloof, relying on her frosty intellect to solve problems. When I think about it that way, I give myself permission to be myself. Like Elsa in Frozen, I can “let it go.” I am Snow Queen! Marvel at my ice palaces!

They help us appreciate the strengths of other women. It’s easy to observe someone acting in a way we wouldn’t and dismiss her with a nasty epithet: “Skank.” “Bitch.” “Snob.” When we keep the archetypes in mind, we can move past that initial, shallow reaction (a Medusa’s reaction, by the way) to ask a better question: “Which archetype is she representing?” I don’t mean to suggest we take women’s goodness on faith; there are plenty of toxic women around, just as there are plenty of toxic men, and not all female behavior is well-intentioned. What I do suggest is that we give the woman whose behavior seems alien a second look and ask ourselves not what’s wrong with her, but what we might learn from her.

Caroline, my former colleague whose story appears in chapter 1, was a classic Temptress, her fishnet stockings and flirtatious manner earning her more than a few side-eyes from the women at our company. Caroline went on to become a much-admired CEO, an award-winning entrepreneur, and a columnist for a major newspaper. I now realize I spent too much energy side-eyeing, not enough energy watching and learning.

They help us stretch beyond our comfort zone. Even if we find multiple archetypes congenial, there will always be some we find less so, and it’s these, the ones we tend to suppress, that represent our opportunities for growth. Not that the leadership thinkers who tell us to play to our strengths are wrong; as I’ve said, it’s no use trying to turn ourselves into something we’re not. Playing to strengths, however, is a strategy more applicable to men than to women. Men, remember, can afford to be one-dimensional: they can set their sights on a goal, marshal their resources as tinker, tailor, soldier, or spy, and count on their unique skills to carry them through. James Bond never has to be Dirty Harry for the weekend. Samwell Tarly never has to be Jon Snow. We women, on the other hand, don’t have the luxury to operate in one dimension. And why would we even try? Sure, we have particular talents and should make the most of them, but the real key to our success is our range, wider than any man’s. For us, an expansion of repertoire holds more promise than reprisals of our greatest role.

And if we seek it, we’ll likely find the “new” repertoire right there within us. I agree with Tony Binns, a freelance screenwriter who posted this on Facebook:

The hero’s journey fantasy for men is always starting at the bottom and coming into your own, so you are the complete badass at the end. The hero’s journey fantasy

for women is to be acknowledged for the power they already possess.

This has real-world echoes. Men have been told to roll up shirt-sleeves and work their way to the top, whereas women are struggling to be heard, to not be

interrupted, to be taken seriously, to not have their ideas stolen, and to have equal pay and opportunity as their male counterparts. Men fight for position; women

fight for recognition.

***

Woman is born free, yet everywhere she is in chains: chains of discrimination, violence, abuse, limitation, trauma, self-doubt, self-absorption, fear, anger, shame.

The good news: by breaking big, we may break the chains.

There’s a natural progression for women seeking personal or professional growth: a “developmental model,” as my colleagues in the learning industry used to say. We start out attached to one or two archetypes, operating snugly in our comfort zone. When we find ourselves in situations where our favorite patterns don’t work, we’re apt to fall into the Medusa Trap, directing disdain toward men and even more toward other women. In this effort to puff ourselves up, we may reach for new models and, lacking a full understanding, latch onto their superficial aspects: the domineering Empress, the mocking Jesteress, the timid Escapist. These dress-up games only keep us small and weak, but when we grasp the deep truth of each archetype, reclaiming it from stereotype and building it up from within, we rise tall and mighty.

At the end of this book, having spent time with each archetype, we’ll look to one of the world’s oldest, most popular fairy tales for an example of a woman who masters the entire wheel of fire, earth, water, and air. When we can do the same, not because we have to but because we choose to, then we’ll have accomplished our heroine’s journey—and be insubordinate.

|

Jocelyn Davis is an internationally known author and speaker and the former head of R&D for a global leadership development consultancy.

Her previous business books include Strategic Speed, The Greats on Leadership, and The Art of Quiet Influence. Her latest is a historical novel, The Age of Kali, called “brilliant,” “heretical,” and “deeply moving.” Jocelyn holds master’s degrees in philosophy and Eastern classics. She grew up in a foreign-service family living in many regions of the world, including Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Caribbean. Currently she lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. |

Jocelyn Davis

|