When Life Shakes Us Up and Drops Us on Our Heads

Q&A with Author

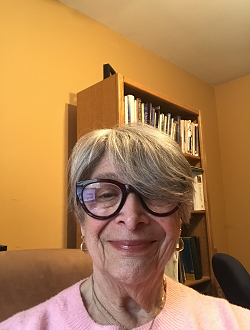

Bette Ann Moskowitz

Bette Ann Moskowitz

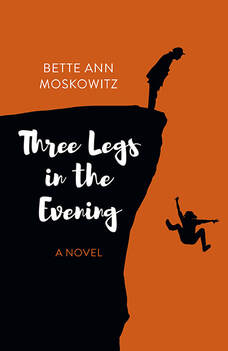

Bette Ann Moskowitz is one of my favorite authors, so I recently asked her about her latest book, Three Legs in the Evening, which is a gripping look at life’s fragilities, loss, change and family. It also happens to be excerpted in Sanctuary this month, so take a look.

~ Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor

~ Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor

Let's start by discussing one of my favorite quotes from the book: "You can't go east all your life and end up in the west.”

At the beginning of the story, your spitfire protagonist, Sally, seems to cling to moderation and the familiar, fearing she’ll lose her grip with too much change happening too quickly. Do you think this is a common fear that women of a certain age have?

I think any change makes people nervous and rapid change even more so; this goes double for older people, because our habits are so much more entrenched, and we are so much more invested in them. Older women, in particular, tend to haul in the drawbridge, so to speak, when it comes to new things.

I know in my own life, and the lives of the women I know, this is true. But consider this: maybe we are simply shifting gears, because all the important changes are happening within. (Changes in our own bodies, to begin with. I can’t tell you how many women I know who have said a variation of: ‘I am not the woman I see in the mirror; inside I am still the little girl my dad called sugar.’) Change – in our circumstances as well as our own bodies – is enormous at my age. And yes, we may fear it, but we also take it as it comes.

At the beginning of the story, your spitfire protagonist, Sally, seems to cling to moderation and the familiar, fearing she’ll lose her grip with too much change happening too quickly. Do you think this is a common fear that women of a certain age have?

I think any change makes people nervous and rapid change even more so; this goes double for older people, because our habits are so much more entrenched, and we are so much more invested in them. Older women, in particular, tend to haul in the drawbridge, so to speak, when it comes to new things.

I know in my own life, and the lives of the women I know, this is true. But consider this: maybe we are simply shifting gears, because all the important changes are happening within. (Changes in our own bodies, to begin with. I can’t tell you how many women I know who have said a variation of: ‘I am not the woman I see in the mirror; inside I am still the little girl my dad called sugar.’) Change – in our circumstances as well as our own bodies – is enormous at my age. And yes, we may fear it, but we also take it as it comes.

So, I have to ask. Would your personal “battle cry” be: Go west!

Hmm. I am attracted to the idea, but I don’t know. The likelihood that if you keep on going in the same direction you’ll get where you’re headed, or if you keep doing something over and over you’ll get it right, really does make sense to me. On the other hand, life shakes us up and drops us on our heads often enough for us to realize that nothing is certain. Realizing that is growth, and accepting it is wisdom. I think the key in that adage (which I am proud to have, I believe, invented) is in the adverb ‘not.’ What Sally learns is that you can go east all your life, and yet end up in the west. No guarantees, after all. That’s what makes life so exciting and terrifying. The surprise of it all.

If you’re surrounded by death, do you become immune to it?

Not immune, Myrna. Maybe resigned? Too familiar with? Dying means coming to an end, and that is a difficult concept to wrap your head around. Even when you are very sick, or death comes close to loved ones, you keep your distance from the idea that one day you or they will cease to exist. Even at those extreme ends of life, the persistence of hope remains a force, and as long as it does, the unreality of ending remains, too.

Hmm. I am attracted to the idea, but I don’t know. The likelihood that if you keep on going in the same direction you’ll get where you’re headed, or if you keep doing something over and over you’ll get it right, really does make sense to me. On the other hand, life shakes us up and drops us on our heads often enough for us to realize that nothing is certain. Realizing that is growth, and accepting it is wisdom. I think the key in that adage (which I am proud to have, I believe, invented) is in the adverb ‘not.’ What Sally learns is that you can go east all your life, and yet end up in the west. No guarantees, after all. That’s what makes life so exciting and terrifying. The surprise of it all.

If you’re surrounded by death, do you become immune to it?

Not immune, Myrna. Maybe resigned? Too familiar with? Dying means coming to an end, and that is a difficult concept to wrap your head around. Even when you are very sick, or death comes close to loved ones, you keep your distance from the idea that one day you or they will cease to exist. Even at those extreme ends of life, the persistence of hope remains a force, and as long as it does, the unreality of ending remains, too.

What is Sally’s best coping mechanism?

Oh, hands down it is her ability to wrap up whatever she is coping with into words. ‘If you can write it, you can live it,’ basically. And I guess, in that way, my character and I are similar. To me, life is a long story, and if I can tell it (to myself, and then maybe to you), I can endure it. Figuring out the ‘grammar’ of every experience begins by putting it into language I can understand. Sally finds her courage in being able to name what hurts. It puts the experience into a container, with dimensions that are measurable – syllables, lines, rhymes, rhythms. Rip her heart out, and she is going to try and contain it into iambic pentameter!

One of the reasons this story is so endearing is because it doesn’t turn maudlin. The story points out so many inevitabilities: our minds and bodies give us so many challenges as we age; we lose many of our loved ones; we’ll never have the big questions all figured out. Humor is woven expertly into the story. We laugh AND cry with Sally. In your opinion, is having a sense of humor necessary to keep things in perspective?

Oh, hands down it is her ability to wrap up whatever she is coping with into words. ‘If you can write it, you can live it,’ basically. And I guess, in that way, my character and I are similar. To me, life is a long story, and if I can tell it (to myself, and then maybe to you), I can endure it. Figuring out the ‘grammar’ of every experience begins by putting it into language I can understand. Sally finds her courage in being able to name what hurts. It puts the experience into a container, with dimensions that are measurable – syllables, lines, rhymes, rhythms. Rip her heart out, and she is going to try and contain it into iambic pentameter!

One of the reasons this story is so endearing is because it doesn’t turn maudlin. The story points out so many inevitabilities: our minds and bodies give us so many challenges as we age; we lose many of our loved ones; we’ll never have the big questions all figured out. Humor is woven expertly into the story. We laugh AND cry with Sally. In your opinion, is having a sense of humor necessary to keep things in perspective?

|

Myrna, there are very few things in my life that I consider pure luck: marrying my late husband is one. Having a sense of humor is another. You can’t get a sense of humor if you don’t have one, and telling someone to have or get one is, I always say, like telling someone to be tall – impossible unless you are tall. Whether it is by nature or nurture, I’m not sure, but I do know my father saw the world in an ironic way, like a pratfall waiting to happen. I have always been drawn to the spot where funny and sad meet and slug it out.

|

"I have always been drawn to the spot where funny and sad meet and slug it out. " ~ Bette Ann Moskowitz |

I will say that practicing humor makes it easier to ‘use’ in getting through life. Sometimes, I have to ask myself what in the world is funny about the funeral, and asking this allowed me to come up with the opening scene of Three Legs in the Evening. And that ‘practice’ certainly does keep things in perspective and make life better.

You write, “Sally's Alzheimer's was the freedom from everything.” Sally was proud of being a wordsmith, but she was losing her words due to this terrible disease. Your mother died from Alzheimer’s disease, and many of our readers have also experienced a sense of helplessness while watching a loved one decline cognitively. Could you explain what you mean by “freedom?”

You write, “Sally's Alzheimer's was the freedom from everything.” Sally was proud of being a wordsmith, but she was losing her words due to this terrible disease. Your mother died from Alzheimer’s disease, and many of our readers have also experienced a sense of helplessness while watching a loved one decline cognitively. Could you explain what you mean by “freedom?”

As you know, I have been writing about aging and dementia for a long time. The first time was when my mother, a bright and active woman, began to decline cognitively. I felt what anyone who has a loved one going through this feels. You are in the grip of pain and fear that never leaves you. I wanted more than anything to hold my mother’s hand as far as I could on her terrifying journey. But I could only go so far, and I had to watch her enter a world where up was down, open was shut, soft was loud, and my father was the stranger sitting next to her in the nursing home. Then, I noticed something interesting: once she was well into her dementia (‘gone,’ ‘over the hump’), she was calmer, less agitated, not afraid.

|

"Giving Sally that ‘freedom’ is one of the reasons I am so deeply proud of this book. I feel as though I have, at least imaginatively, completed the journey my mother took." ~ Bette Ann Moskowitz |

Sally’s ‘freedom’ is what I imagine happens when she is well ‘over the hump.’ Her new reality does not have words, but it has sensation, and as long as it feels good, she doesn’t have to parse it out anymore. She is free to feel it. Giving Sally that ‘freedom’ is one of the reasons I am so deeply proud of this book. I feel as though I have, at least imaginatively, completed the journey my mother took. What do you hope is the biggest takeaway for readers? |

As always, once the book is out of my hands, I don’t have a say anymore. It is up to the readers. If I have any wish, it is that they will enjoy the read, and at the end, maybe say something like, ‘Yes, that’s what life is like,’ and even if it is not their truth, it is truthful.

What's next for Bette?

Who knows? Another book, certainly. Maybe about baseball.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I find sanctuary first and always with a notebook in my hand or sitting in front of a blank screen. But I also find sanctuary with my dog, Steffi, on my lap, on long walks, or sitting on the porch on a summer evening with family and friends and a glass of bourbon.

Who knows? Another book, certainly. Maybe about baseball.

Where do you find sanctuary?

I find sanctuary first and always with a notebook in my hand or sitting in front of a blank screen. But I also find sanctuary with my dog, Steffi, on my lap, on long walks, or sitting on the porch on a summer evening with family and friends and a glass of bourbon.

Bette Ann Moskowitz has been writing all her life. As an accomplished author of six published books, three fiction and three non-fiction, as well as several others in various stages of completion, she says Three Legs in the Evening was a long time coming and a labor of love.

Former songwriter, and writing professor, Bette's essays have appeared in The New York Times, Review of Contemporary Fiction, American Book Review, The Ethel, among others. (Readers can find links to some of her essays on her website, including the popular “New York Times Modern Love” column). She has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship for Creative Non-Fiction and was finalist in the same category. Her popular blog, “Vinegar Mother: A Tart Take On The World,” has been appearing every week for four years – through loss, through the pandemic, she keeps writing, as the world spins on.

Former songwriter, and writing professor, Bette's essays have appeared in The New York Times, Review of Contemporary Fiction, American Book Review, The Ethel, among others. (Readers can find links to some of her essays on her website, including the popular “New York Times Modern Love” column). She has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship for Creative Non-Fiction and was finalist in the same category. Her popular blog, “Vinegar Mother: A Tart Take On The World,” has been appearing every week for four years – through loss, through the pandemic, she keeps writing, as the world spins on.