Sanctuary's 4th Annual Autism Awareness Issue Proudly Sponsored By:

Navigating Relationships and Workplace Protocol:

Advice and Tips for Those on the Spectrum from Someone Who has Been There

An Interview with Sarah Nannery,

Director of Development for Autism Programming at Drexel University

Director of Development for Autism Programming at Drexel University

|

Sarah Nannery is Director of Development for Autism Programming at Drexel University. She holds a master’s degree in conflict transformation and was recently diagnosed with Autism.

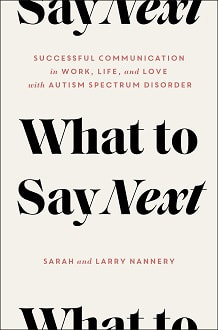

Sarah is the co-author of What to Say Next: Successful Communication in Work, Life and Love with Autism Spectrum Disorder (Simon & Schuster, 2021) which is excerpted in Sanctuary this month. In this book, Sarah reflects on her personal experience living as a professional woman with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Together, with her husband, Larry, she offers timely advice in this communication guide for anyone on the autism spectrum looking to successfully navigate work, life and love. |

Editor’s Note: Some of Sarah’s comments point to universal issues and, therefore, can be applied for neurotypical people as well. However, many of these issues are exacerbated tenfold for someone on the spectrum.

Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor, spoke with Sarah about how people on the autism spectrum can successfully manage personal relationships and workplace protocol.

Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor, spoke with Sarah about how people on the autism spectrum can successfully manage personal relationships and workplace protocol.

How old were you when you were you diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)? Do you believe an earlier diagnosis would have made a difference?

I was 31 when I was diagnosed. It may have been helpful to have known earlier. It might have changed my internal narrative. I was always thinking, ‘Why don’t I fit in?’ I could have given myself some grace or looked for support.

Do you feel that a romantic relationship with a neurotypical person is easier to navigate than a romantic relationship with another person on the spectrum?

For me, any type of romantic relationship is difficult. With someone on the spectrum – a person who communicates the same way as you do – there might be a more intuitive understanding. On the other hand, when you have two people with communication difficulties, it could make things more difficult in some situations.

Many people think of an [ideal] relationship as each person giving half of the time – 50/50.

I was 31 when I was diagnosed. It may have been helpful to have known earlier. It might have changed my internal narrative. I was always thinking, ‘Why don’t I fit in?’ I could have given myself some grace or looked for support.

Do you feel that a romantic relationship with a neurotypical person is easier to navigate than a romantic relationship with another person on the spectrum?

For me, any type of romantic relationship is difficult. With someone on the spectrum – a person who communicates the same way as you do – there might be a more intuitive understanding. On the other hand, when you have two people with communication difficulties, it could make things more difficult in some situations.

Many people think of an [ideal] relationship as each person giving half of the time – 50/50.

|

Sarah explains that a relationship between a person on the spectrum and a neurotypical person might seem very skewed.

My husband [who is neurotypical] frequently helps me with situations with friends and at social functions – things a partner might not typically do. One time, I was leaving a party with my kids before saying goodbye to someone I needed to say goodbye to. My husband gave me a gentle reminder. When I’m juggling a lot of things at once, I’m not thinking about social etiquette. I’m not trying to be rude. I might just be focused on my kids or something else [that has my complete focus]. |

“There are different contexts in which one partner will excel and the other will flounder, and vice versa…The key is not to strive for equality, but to find equity. To continually seek a balance that is fair and just for the strengths, weaknesses, needs and desires of both partners.” (What to Say Next, by Sarah and Larry Nannery) |

|

Sarah and Larry Nannery

Photo Credit: John Robert Hoffman |

Many people with ASD super-obsess over a new relationship. They might contact the person too often in the beginning or assume the relationship is serious when, in fact, it is not. Any advice on keeping a relationship light, not jumping in too fast, or being able to let go when it’s over?

I didn’t date a lot. It’s tough. Dating is a performance, and I’m performing every day. For me, if I’m spending energy on a relationship, I want it to be worth it. For someone who has autism, it doesn’t feel like you’re committing too fast. It doesn’t feel quick at all. Other people take a while to warm up. So, I would play an internal game with myself so that I wouldn’t have expectations. Each date or moment would exist by itself. I would meet someone for coffee and then tell myself, ‘This is just once. I probably won’t see him again.’ It was a way to slow myself down and not have unreasonable expectations. |

For most young women, calling a girlfriend just to say hi or complimenting a friend’s new hairstyle comes naturally. Females with ASD have a harder time navigating these social niceties. What has been your experience in this area?

When I was growing up, all of my friends were guys. I didn’t understand the dance the girls were doing. When it comes to gender socialization, girls are typically better at communicating than boys. It’s just how we’re socialized from the beginning.

I have one or two women I’m close with now. Finding something we both enjoyed was especially important. Then, the friendship would develop from there.

I don’t tell people I have ASD right away. I spend time with people first to find out if the relationship will be worth my time.

When I was growing up, all of my friends were guys. I didn’t understand the dance the girls were doing. When it comes to gender socialization, girls are typically better at communicating than boys. It’s just how we’re socialized from the beginning.

I have one or two women I’m close with now. Finding something we both enjoyed was especially important. Then, the friendship would develop from there.

I don’t tell people I have ASD right away. I spend time with people first to find out if the relationship will be worth my time.

|

Is it necessary to have a mentor at the workplace – someone who can help you navigate office communications, politics and hierarchy?

Yes. It’s essential to have someone who can help you navigate these situations – even if this person is outside the office. My husband helps me. I might explain an issue I struggled with at the office and ask for his opinion on how to handle it. In terms of finding people within the office who are sympathetic, you need to learn to listen to the ‘right’ people in terms of accepting advice. This should be someone who does well with most of the people in your workplace – someone who is well-liked and respected by most. Having someone you can rely on gives you a chance to offload an issue you are not certain about. Perhaps you thought someone looked at you strangely during a meeting. You could ask, ‘Did I say something weird?’ |

On the Job: Sarah (left) with Meredith Bloom,

Director of Philanthropic Initiatives at the AJ Drexel Autism Institute |

Should people on the spectrum disclose their disability to an employer upfront?

I’ve worked a lot in the nonprofit industry, and I think it really depends on the workplace and the people you are working with. My autism doesn’t affect a lot of my work. In my case, I decided to disclose to those organizations with an autism focus but did not disclose to those that had nothing to do with autism.

Another thing you can do is to be specific about what your needs are. For instance, I might need to see questions or topics prior to meetings.

Sarah explained that specific requests that align with your skill set or how you function well in the office, rather than mentioning autism, is a viable option.

What are some typical, workplace pitfalls for those with ASD? Any tips for how to navigate or spot ahead of time?

It’s a lot of little things, such as those things that aren’t even related to work. It’s the interoffice relationships that pile up throughout the day. I’m someone who over-analyzes things all the time. Someone may not have meant to give me a ‘weird look.’ Maybe they were just thinking about something while looking in my direction, but now I’m trying to figure out what I did wrong and start to compensate.

I’m also a perfectionist. I might spend an extra week working on something that just needs to get passed on. No one is perfect, and one person can’t do everything.

Any tips for navigating the holiday office party or other types of workplace socials?

For most people, these types of events are a chance to let loose.* For an autistic person, it’s the exact opposite. You have to think twice as hard about what to do and how to present yourself. You might prepare yourself by thinking about options ahead of time: ‘Who will I talk to?’ or “If I see my boss, what are one or two things I can talk about?’

I’ve worked a lot in the nonprofit industry, and I think it really depends on the workplace and the people you are working with. My autism doesn’t affect a lot of my work. In my case, I decided to disclose to those organizations with an autism focus but did not disclose to those that had nothing to do with autism.

Another thing you can do is to be specific about what your needs are. For instance, I might need to see questions or topics prior to meetings.

Sarah explained that specific requests that align with your skill set or how you function well in the office, rather than mentioning autism, is a viable option.

What are some typical, workplace pitfalls for those with ASD? Any tips for how to navigate or spot ahead of time?

It’s a lot of little things, such as those things that aren’t even related to work. It’s the interoffice relationships that pile up throughout the day. I’m someone who over-analyzes things all the time. Someone may not have meant to give me a ‘weird look.’ Maybe they were just thinking about something while looking in my direction, but now I’m trying to figure out what I did wrong and start to compensate.

I’m also a perfectionist. I might spend an extra week working on something that just needs to get passed on. No one is perfect, and one person can’t do everything.

Any tips for navigating the holiday office party or other types of workplace socials?

For most people, these types of events are a chance to let loose.* For an autistic person, it’s the exact opposite. You have to think twice as hard about what to do and how to present yourself. You might prepare yourself by thinking about options ahead of time: ‘Who will I talk to?’ or “If I see my boss, what are one or two things I can talk about?’

|

“These situations can be particularly confusing for someone who already has difficulty with face-to-face communication, because now, the social ‘rules’ bend a little bit. Suddenly, your ‘work life,’ which has a very different set of social rules, is mixing with your ‘social life,’ and it can be hard to suss out exactly how (and how much) to bend the work life rules to make room for the social interaction.” (What to Say Next, by Sarah and Larry Nannery) |

I do push myself a bit to interact with those I might not normally interact with. I also pay attention to how many people are in the room, so I don’t leave too early. It might work to go in with a certain number in mind. For instance: Wait to leave until about 20 percent of attendees have left.

*Even though a shy, neurotypical person might find office socials to be uncomfortable as well, these types of situations can be downright terrifying for a person with ASD, causing a meltdown or a very uncomfortable social faux pas. This mixing of professional and social is a recipe for disaster for many people on the spectrum. |

Any guidelines for how to ask for help from a colleague so you don’t badger or overstep when a person seems initially willing to help and guide you?

If this is a colleague who knows your situation, you might say, ‘It’s hard for me to tell if I’m asking for too much, so please let me know.’ Then, if the time comes, your colleague will know that he or she can be truthful about letting you know the boundaries.

If the colleague is someone you have not disclosed to, you might discuss the situation with someone outside of the office.

I always try to predict if someone is going to be positive or negative by bringing up autism in a context that’s not related to the workplace. One of my children has autism, so I might bring that up. If the person responds, ‘Oh, my cousin has autism, too,’ it’s a good sign. If the person says, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry,’ I won’t disclose.

Please offer some tips on learning to see the ‘big picture’ as this is a struggle for many people on the spectrum.

I have this issue with everything, not just in the workplace. I get lost in the details that other people don’t even notice. At a 3,000-foot view, it’s just fog for me because I’m not used to being up there.

One exercise is to learn to recognize when you need to act on something. If someone brings up an issue that I didn’t think would come up at a meeting, I ask myself, ‘What am I missing?’

It’s also not a bad thing to ask your boss for a broader view of what’s going on. A willingness to understand the big picture is professional. Ask for the ‘why.’ If you’ve found a mentor, you might ask this person about the broader view if you’re not as comfortable asking your boss.

I also check in with personal situations. I’ll ask my husband, ‘Why are we doing this again?’

Where do you find sanctuary?

For me, it’s the Harry Potter series. I have the audio books. I know every moment in the stories. My sanctuary is listening to these audio books.

We talked a bit about the books and the frenzy surrounding the release of new titles at the time as well as those on the spectrum being super-focused on specific interests.

Sarah laughed. Don’t even get me started.

|

Click Book Cover for Excerpt

|

"If I am thinking something, it takes an extra few steps for me to realize that the person next to me might not be thinking the same thing, and therefore, it would be a good idea for me to SAY the thing that I am thinking, if it is important. This tendency to assume that other people are already thinking what I'm thinking means that I may keep more things internalized, because I won't see the need to externalize them in the moment."

~ Sarah Nannery |