June 2019 Featured Interview

Special Issue: Celebrating the Men in Our Lives

|

|

Interview with

Dr. Irwin Redlener

President Emeritus and Co-founder of the Children's Health Fund

Photo Credit: IrwinRedlener.org

About Irwin:

Irwin Redlener, M.D., is president emeritus and co-founder of the Children’s Health Fund (CHF), a unique nonprofit organization dedicated to providing health care to disadvantaged children and families in the United States.

Under his leadership, CHF has grown to become a national network of more than 50 mobile and fixed site pediatric clinics providing more than 250,000 healthcare encounters each year in 25 of the nation’s most medically underserved urban and rural communities. Irwin has initiated a new special initiative on “Healthy and Ready to Learn” which endeavors to ensure that no child suffers from health-related concerns that can interfere with early development or success in school. He directs the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at the Columbia University’s Earth Institute and founded and directs the Program on Child Well-Being and Resilience.

Irwin has published, spoken and testified extensively on the subjects of health care for medically underserved and indigent children and national health policy. He is the author of Americans At Risk: Why We Are Not Prepared For Megadisasters and What We Can Do Now (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2006), and his book The Future of Us (Columbia University Press, 2017) discusses the challenges of assuring that every child reaches his or her full potential and the implications of child-friendly policies on the long-term success of societies.

From 1971-73, he directed a rural, VISTA-run health center in East Arkansas. Irwin also served as director of grants and medical director of USA for Africa and Hands Across America. In 1993, he served as a member of the White House Task Force on Health Reform under President Clinton. From 1997 through 2003, Irwin had a lead role in the development of the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, where he served as president and chief spokesperson. This hospital remains one of the most advanced and innovative facilities of its kind in the world.

Irwin Redlener, M.D., is president emeritus and co-founder of the Children’s Health Fund (CHF), a unique nonprofit organization dedicated to providing health care to disadvantaged children and families in the United States.

Under his leadership, CHF has grown to become a national network of more than 50 mobile and fixed site pediatric clinics providing more than 250,000 healthcare encounters each year in 25 of the nation’s most medically underserved urban and rural communities. Irwin has initiated a new special initiative on “Healthy and Ready to Learn” which endeavors to ensure that no child suffers from health-related concerns that can interfere with early development or success in school. He directs the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at the Columbia University’s Earth Institute and founded and directs the Program on Child Well-Being and Resilience.

Irwin has published, spoken and testified extensively on the subjects of health care for medically underserved and indigent children and national health policy. He is the author of Americans At Risk: Why We Are Not Prepared For Megadisasters and What We Can Do Now (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2006), and his book The Future of Us (Columbia University Press, 2017) discusses the challenges of assuring that every child reaches his or her full potential and the implications of child-friendly policies on the long-term success of societies.

From 1971-73, he directed a rural, VISTA-run health center in East Arkansas. Irwin also served as director of grants and medical director of USA for Africa and Hands Across America. In 1993, he served as a member of the White House Task Force on Health Reform under President Clinton. From 1997 through 2003, Irwin had a lead role in the development of the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, where he served as president and chief spokesperson. This hospital remains one of the most advanced and innovative facilities of its kind in the world.

About CHF:

Irwin co-founded CHF with his wife, Karen, and Paul Simon. Since 1987, Children’s Health Fund (CHF) has been delivering high-quality, comprehensive health care to children in some of the most impoverished and underserved communities in the country. From South Los Angeles to the Mississippi Delta, from the South Bronx to southern Arizona, every year its 26 national programs and fleet of 50 mobile medical clinics provide care to more than 100,000 children and their families living in poverty. Care is delivered to more than 400 service sites, including, but not limited to, fixed-site clinics, schools, Head Start centers, homeless and domestic violence shelters, and community agencies.

The organization also works to reduce health barriers to learning, brings the voice of children to local and national policy debates, and in times of disaster, activates care for those in need.

Irwin co-founded CHF with his wife, Karen, and Paul Simon. Since 1987, Children’s Health Fund (CHF) has been delivering high-quality, comprehensive health care to children in some of the most impoverished and underserved communities in the country. From South Los Angeles to the Mississippi Delta, from the South Bronx to southern Arizona, every year its 26 national programs and fleet of 50 mobile medical clinics provide care to more than 100,000 children and their families living in poverty. Care is delivered to more than 400 service sites, including, but not limited to, fixed-site clinics, schools, Head Start centers, homeless and domestic violence shelters, and community agencies.

The organization also works to reduce health barriers to learning, brings the voice of children to local and national policy debates, and in times of disaster, activates care for those in need.

Nancy Burger, senior editor, talked to Dr. Redlener about his lifelong mission to support the medically underserved in this country and his co-creation of the Children's Health Fund.

Could you walk me through the genesis of CHF? What led you, Karen and Paul Simon to visit the Martinique Hotel in New York City?

First of all, for years before the Children's Health Fund began, I had been working with the medically underserved indigent populations in a variety of settings around the country. However, the roots really are an experience I had for two years in East Arkansas where I ran a government clinic under a program called VISTA, which was the volunteer Peace Corps, now called Americorps. I spent two years in a very, very poor, racially torn environment in East Arkansas - it was the sixth poorest county in America at the time, and it had lots of issues. So, this is something I always intended to do with my career.

I had been the director of grants and medical director for USA for Africa - the organization created by Michael Jackson, Lionel Ritchie and some other folks. They recorded the song We Are the World one night at the end of 1984 with about every A-lister in the music business, and that included Paul Simon. At the time, Paul was recording his Graceland album, and every morning would walk from his apartment on Central Park West to the recording studio where he would pass a homeless woman named Maria. He eventually started speaking to her, and they developed a conversational relationship. One day, she wasn't there, and he became pretty distressed about it. He tried to find her and enlisted help from the city, but he never saw her again. He then became pretty interested in the problem of homelessness.

How did you meet him?

I was in Los Angeles at a board meeting for USA for Africa and was in the executive director's office when he received a call from Paul who said, ‘Hey, listen. I know we raised a lot of money from the song We Are the World.* Could we use some of the money that we raised to support homelessness and children's issues here in New York City?’ But the ED said they couldn't because they had promised donors that the money was all going to help sub-Saharan Africa deal with its drought and famine. He suggested that Paul meet with me in New York and talk about what I was trying to do. So, I called Paul when I got back to New York and ended up taking him on a tour of some of these notorious welfare hotels in New York City, including the Martinique.

*The song We Are the World raised approximately 65 million dollars.

Were you surprised at what you saw when you took him to these places?

I've worked with a lot of poor kids in different environments - internationally and in disaster relief programs. It's not like I was naïve to bad conditions for children. But I was pretty floored by what I saw in these shelters in New York City in the fall of 1986.

What was the next step?

A few days later, I told Paul that one thing these children weren't getting was health care, that I had this thought about creating a mobile pediatric clinic that we could take to homeless shelters. He really liked the idea. He was about to go on his Graceland tour, so he gave my wife Karen* his office, and she designed the rolling clinics. I put together the program, and that's how it got started.

*Karen Redlener is a co-founder of CHF with Irwin Redlener and Paul Simon.

That unit was called the "Big Blue Bus," and the program grew into a national network of pediatric care programs across the country.

Yes. Paul tried to raise the money to buy the bus from his pals in the business, but he wasn't successful at that; so he decided to just pay for it himself. That mobile unit got delivered and was operational around November of 1987 and got immediate attention with a front-page story in The New York Times. But I was pretty clear that one unit wasn't going to be enough to serve New York City. So, Paul did a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden and raised half a million dollars. We ended up with five mobile units in New York City. Then, we started to expand, and we now have 50 units across the country.

Was that the plan from the beginning?

When I was first putting this together, I clearly saw it as a model for underserved children to get health care. When I worked in the clinic in Arkansas, I made house calls every evening to those children who couldn't get to the clinic. So, this idea of bringing health care to the families that couldn't get to us, no matter what it took, was in the front of my mind when we were putting this program together.

The CHF website says that its mobile and fixed site pediatric clinics provide services more than 250,000 times a year in 25 of our nation's more underserved communities. Are these supported by local governments, or is the effort primarily supported through philanthropy?

We raise between $12 million and $14 million a year through philanthropy, privately. But it's a stimulus to raising other funds. We also receive money from government sources. We never charge anybody for health care, but if they have private or employer-based insurance, we will collect that.

You've dedicated your career to delivering quality health care to children. How has that mission evolved over the years?

Most of my career has been focused on getting good-quality health care to children, but over the last decade that has expanded. I'm now focused on making sure that children - no matter what environment they come from - are successful, ready for adult life, healthy, educated, have the social support they need, and live in a stable housing situation. We can't have healthy children getting a crappy education or have children getting educated in a great school system but unable to access the health care they need. Children who are exposed to a certain number of adverse childhood experiences (ACES), such as homelessness, domestic violence, child abuse, etc., can end up with significant mental health issues that carry lifelong consequences.

Five years ago you started a new initiative called Healthy and Ready to Learn to ensure that disadvantaged children are not hampered by health conditions that are known to interfere with learning.

Yes, we want to break down the silos between health and education for children and make sure we're not missing anything that can impede learning. For example, we might screen a school in an underperforming area and find that 25% to 30% of the children fail the vision screening and need corrective glasses. If a kid can't read the blackboard, that's a problem. You can't have educational success with those types of issues.

Could you walk me through the genesis of CHF? What led you, Karen and Paul Simon to visit the Martinique Hotel in New York City?

First of all, for years before the Children's Health Fund began, I had been working with the medically underserved indigent populations in a variety of settings around the country. However, the roots really are an experience I had for two years in East Arkansas where I ran a government clinic under a program called VISTA, which was the volunteer Peace Corps, now called Americorps. I spent two years in a very, very poor, racially torn environment in East Arkansas - it was the sixth poorest county in America at the time, and it had lots of issues. So, this is something I always intended to do with my career.

I had been the director of grants and medical director for USA for Africa - the organization created by Michael Jackson, Lionel Ritchie and some other folks. They recorded the song We Are the World one night at the end of 1984 with about every A-lister in the music business, and that included Paul Simon. At the time, Paul was recording his Graceland album, and every morning would walk from his apartment on Central Park West to the recording studio where he would pass a homeless woman named Maria. He eventually started speaking to her, and they developed a conversational relationship. One day, she wasn't there, and he became pretty distressed about it. He tried to find her and enlisted help from the city, but he never saw her again. He then became pretty interested in the problem of homelessness.

How did you meet him?

I was in Los Angeles at a board meeting for USA for Africa and was in the executive director's office when he received a call from Paul who said, ‘Hey, listen. I know we raised a lot of money from the song We Are the World.* Could we use some of the money that we raised to support homelessness and children's issues here in New York City?’ But the ED said they couldn't because they had promised donors that the money was all going to help sub-Saharan Africa deal with its drought and famine. He suggested that Paul meet with me in New York and talk about what I was trying to do. So, I called Paul when I got back to New York and ended up taking him on a tour of some of these notorious welfare hotels in New York City, including the Martinique.

*The song We Are the World raised approximately 65 million dollars.

Were you surprised at what you saw when you took him to these places?

I've worked with a lot of poor kids in different environments - internationally and in disaster relief programs. It's not like I was naïve to bad conditions for children. But I was pretty floored by what I saw in these shelters in New York City in the fall of 1986.

What was the next step?

A few days later, I told Paul that one thing these children weren't getting was health care, that I had this thought about creating a mobile pediatric clinic that we could take to homeless shelters. He really liked the idea. He was about to go on his Graceland tour, so he gave my wife Karen* his office, and she designed the rolling clinics. I put together the program, and that's how it got started.

*Karen Redlener is a co-founder of CHF with Irwin Redlener and Paul Simon.

That unit was called the "Big Blue Bus," and the program grew into a national network of pediatric care programs across the country.

Yes. Paul tried to raise the money to buy the bus from his pals in the business, but he wasn't successful at that; so he decided to just pay for it himself. That mobile unit got delivered and was operational around November of 1987 and got immediate attention with a front-page story in The New York Times. But I was pretty clear that one unit wasn't going to be enough to serve New York City. So, Paul did a benefit concert at Madison Square Garden and raised half a million dollars. We ended up with five mobile units in New York City. Then, we started to expand, and we now have 50 units across the country.

Was that the plan from the beginning?

When I was first putting this together, I clearly saw it as a model for underserved children to get health care. When I worked in the clinic in Arkansas, I made house calls every evening to those children who couldn't get to the clinic. So, this idea of bringing health care to the families that couldn't get to us, no matter what it took, was in the front of my mind when we were putting this program together.

The CHF website says that its mobile and fixed site pediatric clinics provide services more than 250,000 times a year in 25 of our nation's more underserved communities. Are these supported by local governments, or is the effort primarily supported through philanthropy?

We raise between $12 million and $14 million a year through philanthropy, privately. But it's a stimulus to raising other funds. We also receive money from government sources. We never charge anybody for health care, but if they have private or employer-based insurance, we will collect that.

You've dedicated your career to delivering quality health care to children. How has that mission evolved over the years?

Most of my career has been focused on getting good-quality health care to children, but over the last decade that has expanded. I'm now focused on making sure that children - no matter what environment they come from - are successful, ready for adult life, healthy, educated, have the social support they need, and live in a stable housing situation. We can't have healthy children getting a crappy education or have children getting educated in a great school system but unable to access the health care they need. Children who are exposed to a certain number of adverse childhood experiences (ACES), such as homelessness, domestic violence, child abuse, etc., can end up with significant mental health issues that carry lifelong consequences.

Five years ago you started a new initiative called Healthy and Ready to Learn to ensure that disadvantaged children are not hampered by health conditions that are known to interfere with learning.

Yes, we want to break down the silos between health and education for children and make sure we're not missing anything that can impede learning. For example, we might screen a school in an underperforming area and find that 25% to 30% of the children fail the vision screening and need corrective glasses. If a kid can't read the blackboard, that's a problem. You can't have educational success with those types of issues.

|

Another example is we're finding that many of the kids who are falling asleep in class have undertreated asthma that's keeping them up coughing all night long, and they're coming to school exhausted. We're trying to help children and also help the teachers understand that there may be dynamics that are causing a kid to misbehave, fall asleep or act out in class.

Do you find that the parents are engaged and want to learn how to help? I think people would be surprised at how interested and concerned homeless families are about their children. Sometimes they just don't know what's going on with a child, or they might know and not know what to do about it. If a young child is having tooth pain, for example, they can't concentrate in class. But getting dental care when you're on Medicaid is extremely difficult. So, they're caught in these traps and barriers to getting services. This is one of the health barriers to learning that we've identified. |

Photo Credit: CHF Facebook Page

|

Are you seeing change happen from this program?

Yes, because we're educating teachers as to what might be creating behaviors in the students, and we're creating trauma sensitive environments in the schools. Kids that have been traumatized by adverse childhood experiences are coming to school with behavioral and psychological issues, but there's a lot the teachers can do to teach the children self-regulation and to recognize the consequences of conditions they may be experiencing at home. There's a lot happening for those children in addition to the screening for health barriers to learning.

Yes, because we're educating teachers as to what might be creating behaviors in the students, and we're creating trauma sensitive environments in the schools. Kids that have been traumatized by adverse childhood experiences are coming to school with behavioral and psychological issues, but there's a lot the teachers can do to teach the children self-regulation and to recognize the consequences of conditions they may be experiencing at home. There's a lot happening for those children in addition to the screening for health barriers to learning.

|

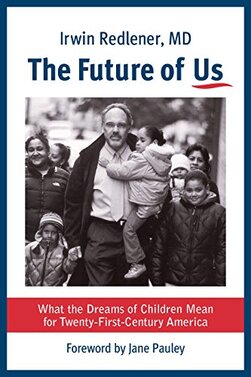

Click Book Cover for More Information

|

The Future of Us discusses the challenges of assuring that every child reaches his or her full potential and the implications of child-friendly policies on the long-term success of societies. Is that an offshoot of your work with CHF?

It might be the other way around. I've written two books. The first was published in 2006 about disaster issues called Americans At Risk: Why We're Not Prepared for Mega disasters and What We Can Do Now. The other book came out in 2017 and is more in line with the issues we're dealing with at CHF. The Future of Us is part memoir and really delves into a lot of these issues that have to do with children who may have had great potential but whose dreams are thwarted by their conditions. When their futures are jeopardized, that's the case for all of us. |

Disaster Relief

Photo Credit: IrwinRedlener.org |

What do you see as the biggest threats to children in our country today?

Poverty, politics and priorities are three big issues. I was a child of the Kennedy-Johnson era, when everything seemed possible. As a young physician-activist, I really thought that we would be solving the problems of poor access to health care for poor children, and we would end childhood poverty in 10 to 15 years. That was my true belief and conviction. And here we are, five decades later, nearly a half century, still dealing with these extraordinary challenges of a persistent, intractable percentage of our population of children in this country that still live in poverty without secure access to care. It's deeply frustrating to me. We are making progress, but it's impeded by systems of government that just aren't working for us.

Where do you find sanctuary? (#WheresYourSanctuary)

Hanging out with Karen and our grandchildren. Five of them live within a couple of blocks of us. We spend a crazy amount of time with them, and it’s joyous. That…and watching Game of Thrones.

Poverty, politics and priorities are three big issues. I was a child of the Kennedy-Johnson era, when everything seemed possible. As a young physician-activist, I really thought that we would be solving the problems of poor access to health care for poor children, and we would end childhood poverty in 10 to 15 years. That was my true belief and conviction. And here we are, five decades later, nearly a half century, still dealing with these extraordinary challenges of a persistent, intractable percentage of our population of children in this country that still live in poverty without secure access to care. It's deeply frustrating to me. We are making progress, but it's impeded by systems of government that just aren't working for us.

Where do you find sanctuary? (#WheresYourSanctuary)

Hanging out with Karen and our grandchildren. Five of them live within a couple of blocks of us. We spend a crazy amount of time with them, and it’s joyous. That…and watching Game of Thrones.