JUNE 2020: Featured Artist

Acclaimed Author

Eugene Mirabelli, Ph.D.

~~~

|

For over sixty years, Eugene (or Gene) Mirabelli, Ph.D., has written novels, short stories, articles and reviews and, for more than half that time, was also teaching literature and writing classes to both undergraduate and graduate students.

Gene grew up in Lexington, Massachusetts, where he attended public schools and worked a variety of jobs during the summers, mostly involving manual labor. In his second year at MIT, he won the undergraduate writing prize and transferred to Harvard University. He later earned an M.A. from Johns Hopkins University and a Ph.D. from Harvard. While teaching at the University at Albany, SUNY, Gene, who is now retired and was appointed Professor Emeritus, and one of his students founded Alternative Literary Programs in the Schools (ALPS), which grew to be one of the most successful arts programs in New York State. In addition to receiving funds for his writing from New York’s Research Foundation, Gene also received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. |

Gene’s literary production has been rich and varied. He has written reviews, interviews and opinion pieces which focus primarily on politics, economics and science. In addition, there are his short stories – science fiction and fantasy tales which have been published in the U.S., Europe, Russia and China.

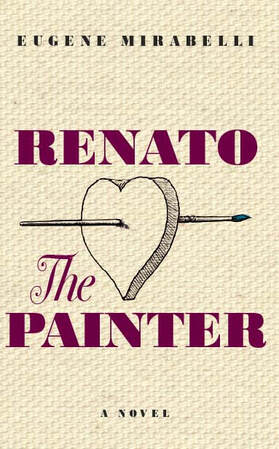

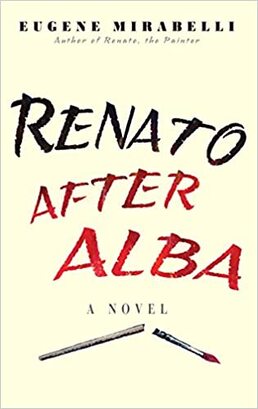

Gene’s last six novels, each one a stand-alone fiction, compose a mosaic which becomes visible only when all the pieces are together. The fourth of these works, The Goddess in Love with a Horse, is a serio-comic genealogy of the Cavallù family, those men and women “known for being handsome, quick-witted and rash” who fill the pages of his other fictions. His most recent works, Renato, the Painter and Renato After Alba, are an extension and enlargement in style and narrative power of what has gone before. Current plans call for all three novels to reappear in one volume, encompassing comic moments, intellectual disputes, sensual pleasures, grief, rage and passion for life.

Gene’s last six novels, each one a stand-alone fiction, compose a mosaic which becomes visible only when all the pieces are together. The fourth of these works, The Goddess in Love with a Horse, is a serio-comic genealogy of the Cavallù family, those men and women “known for being handsome, quick-witted and rash” who fill the pages of his other fictions. His most recent works, Renato, the Painter and Renato After Alba, are an extension and enlargement in style and narrative power of what has gone before. Current plans call for all three novels to reappear in one volume, encompassing comic moments, intellectual disputes, sensual pleasures, grief, rage and passion for life.

Note to Readers: Gene is a mentor and former professor of mine who has become a steadfast friend. He is an incredibly gifted writer and has been a dedicated teacher and guide to so many students over the years. I have treasured his kindness, his sage advice and his confidence in me throughout the years, and I am honored to share just a bit of his journey with you. ~ Myrna Beth Haskell, managing editor

When did you realize you were destined to be a novelist?

My intention when I was growing up was to be a painter. In grammar school, I felt that drawing was my only talent. But the art classes were dropped by the time I was in fifth grade. In high school, I received good grades in both science and English. When it was time to choose a college, I decided to go to MIT. My dad was a professor there, so I had the ability to attend for half the tuition, and I also received a local scholarship, so it just made sense at the time. Then, in my sophomore year, I won a writing contest; it was also around this time that I realized I just wasn’t cut out to be a scientist. Laughing. I was ready to throw myself in the Charles River.

It’s quite the tangled path after this, though.

Okay…so then what?

I still had a desire to be a painter, but I learned that summer [after sophomore year] that the painters my age were an inarticulate group of people, so I wound up at Harvard, enrolling in a lot of literature courses.

Is this when you focused on your writing?

It was at this time that I met and studied with some phenomenal writers. I met the poet Richard Wilbur. To my mind, his handling of language was on par with, say, Keats, and he was a good teacher. I also met William Alfred, who was an incredible playwright and poet. We became lifelong friends. After he died, I was one of the members of the “Friends of William Alfred” – the group established an archive in the Brooklyn College Library in his memory. I had discovered Donne, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Dostoevsky and Faulkner, but I still wanted to paint!

After graduation, around 1952, I took a job as a technical writer for a company in Foxborough, MA, and I rented a furnished room in a house located in nearby Mansfield. I was trying to write at the time, but the train went through there every 30 minutes or so…ALL day long. It was a dismal place to live…and the work was…well, I quit because I couldn’t take it anymore. I worked a bunch of odd jobs after that, and then I received a full-tuition scholarship to Johns Hopkins and completed my master’s in writing there. I wrote book reviews for the Baltimore Sun and, eventually, decided to go back to Harvard for my Ph.D. While there, I wrote my first book, The Burning Air [published in 1959]. Bill [William Alfred] took the manuscript to Houghton Mifflin where it was accepted. It was in the process of being published right around the time I met Margaret [Gene’s wife].

Did I tell you how I met Margaret?

I don’t so. I think I would remember.

I was at the library. I was supposed to be studying for my oral exams, but it was hard to focus. I had this book that was going to be published, and I just wanted to be done. She was an undergrad at the time. I spotted her reading at one of the tables and immediately saw an interesting mix of beauty and strength. Laughing. I was trying to build up courage to walk over and talk with her, when she snuffed out her cigarette and took off! I asked a few people who were there if they knew the woman who had just left. This one girl said her roommate had just been there and showed me a photograph. I thought this can’t be the one. The woman in the photo was modeling a hat for JC Penny, and she just didn’t look like the girl I had just had my eye on – the one in the photo was too sophisticated for me. It turned out that it was her…and we decided to meet and have coffee. And that was the same day that I was supposed to meet the publisher [Houghton Mifflin] to look at a design for the book cover. I remember sitting there thinking…I’m not going to get up and leave this woman! Then, I realized I couldn’t possibly make it to Boston on time, so I called to change the meeting. This was in the fall of 1958, and we got married that next summer.

When did you realize you were destined to be a novelist?

My intention when I was growing up was to be a painter. In grammar school, I felt that drawing was my only talent. But the art classes were dropped by the time I was in fifth grade. In high school, I received good grades in both science and English. When it was time to choose a college, I decided to go to MIT. My dad was a professor there, so I had the ability to attend for half the tuition, and I also received a local scholarship, so it just made sense at the time. Then, in my sophomore year, I won a writing contest; it was also around this time that I realized I just wasn’t cut out to be a scientist. Laughing. I was ready to throw myself in the Charles River.

It’s quite the tangled path after this, though.

Okay…so then what?

I still had a desire to be a painter, but I learned that summer [after sophomore year] that the painters my age were an inarticulate group of people, so I wound up at Harvard, enrolling in a lot of literature courses.

Is this when you focused on your writing?

It was at this time that I met and studied with some phenomenal writers. I met the poet Richard Wilbur. To my mind, his handling of language was on par with, say, Keats, and he was a good teacher. I also met William Alfred, who was an incredible playwright and poet. We became lifelong friends. After he died, I was one of the members of the “Friends of William Alfred” – the group established an archive in the Brooklyn College Library in his memory. I had discovered Donne, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Dostoevsky and Faulkner, but I still wanted to paint!

After graduation, around 1952, I took a job as a technical writer for a company in Foxborough, MA, and I rented a furnished room in a house located in nearby Mansfield. I was trying to write at the time, but the train went through there every 30 minutes or so…ALL day long. It was a dismal place to live…and the work was…well, I quit because I couldn’t take it anymore. I worked a bunch of odd jobs after that, and then I received a full-tuition scholarship to Johns Hopkins and completed my master’s in writing there. I wrote book reviews for the Baltimore Sun and, eventually, decided to go back to Harvard for my Ph.D. While there, I wrote my first book, The Burning Air [published in 1959]. Bill [William Alfred] took the manuscript to Houghton Mifflin where it was accepted. It was in the process of being published right around the time I met Margaret [Gene’s wife].

Did I tell you how I met Margaret?

I don’t so. I think I would remember.

I was at the library. I was supposed to be studying for my oral exams, but it was hard to focus. I had this book that was going to be published, and I just wanted to be done. She was an undergrad at the time. I spotted her reading at one of the tables and immediately saw an interesting mix of beauty and strength. Laughing. I was trying to build up courage to walk over and talk with her, when she snuffed out her cigarette and took off! I asked a few people who were there if they knew the woman who had just left. This one girl said her roommate had just been there and showed me a photograph. I thought this can’t be the one. The woman in the photo was modeling a hat for JC Penny, and she just didn’t look like the girl I had just had my eye on – the one in the photo was too sophisticated for me. It turned out that it was her…and we decided to meet and have coffee. And that was the same day that I was supposed to meet the publisher [Houghton Mifflin] to look at a design for the book cover. I remember sitting there thinking…I’m not going to get up and leave this woman! Then, I realized I couldn’t possibly make it to Boston on time, so I called to change the meeting. This was in the fall of 1958, and we got married that next summer.

|

You got married in less than a year, then?

When you know…well, you just know. Did you always plan to teach, or did you envision life as a full-time writer at some point? In 1965, I got into teaching. It’s really hard to make a living as a full-time writer. It’s possible in pop fiction (romance, science fiction, etc.) if you work very diligently. Even then, it’s not easy. But literary fiction sales are much smaller. Teaching was a regular paycheck, and I wanted a family. I loved the connections with students, but if I had a choice, I would have preferred one semester on and one semester off to write. That would have been ideal. |

L to R: Gene, his daughter Gabriella, and Margaret

|

I took your creative writing class which was very student-centered. We were required to critique our peers’ work – which can be difficult as a young undergrad - but it’s such a good way to learn to be self-critical at the same time. Is there something you learned from your students that you’d like to share?

Yes…well, it’s really the only way to do it. I would wait for the students and sit in one of the chairs, usually placed in a circle.

I remember that.

On the first day, they’d walk in and think I was one of the other students. I liked teaching because I like people. And you have to like people, or at least be very interested in them, if you’re going to be a writer.

What did I learn from my students? A pause. In general, you learn about life through your students in the classroom…the way people are...the way they relate. Students are very open. College students are becoming adults, but they’re not totally there yet, which makes it interesting. At the graduate level, they’re mostly there. They’re starting to figure it all out.

Teaching is a wonderful profession, but I like writing even more.

Technology turned the publishing industry on its head. At some point, there will be no one left who remembers the dusty smell of the “old books” section of the library or the card catalogues. How do you feel about all of this?

The publishing industry went through another big change, even before technology took over – a period of consolidation. The publishing houses needed a better way to make money, so they gradually integrated into larger companies with many imprints that specialized in different genres. It was all about their profit/loss sheets. Eventually, there were only a handful of these traditional publishing houses left. The poets were the ones who were really squeezed out during this transformation.

Years ago, independent presses couldn’t get their books reviewed, but that has all changed. Right now, I’m with McPherson & Company [an independent press], and they have a National Book Award winner.*

Of course, in this [digital age], book stores have been really hurt, too. They’ve had to make adjustments – selling postcards, calendars and toys.

*Established in 1950, the National Book Awards are American literary prizes administered by the National Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization. (William Faulkner, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker are among the many notable winners.)

And they’ve added cafes to attract customers – to establish a gathering place to socialize.

Yes. That’s true.

Your Italian heritage comes through in your novels. I would love it if you’d share a fond memory from your childhood that screams Italian upbringing.

Well, I grew up in a house where copies of Dante and Benvenuto Cellini were on the shelf and Italian was spoken in the kitchen.

Thinking back to my childhood, it would probably have to be BIG dinners and BIG holidays – big Christmases, big Easters. For Italians, life is built around the dinner table. On Sundays, my parents, my brother and I would get together with family. I remember when I was young, I had this playmate who told me his family was going to celebrate Thanksgiving with the neighbors. I thought what an emaciated, thin life these people have – to have no relatives. My mother’s mother had nine children, and they all had children, so there were always all these aunts and uncles and cousins. We’d have these huge family gatherings.

But there are two sides to this. Family can be a great safety net. On the other hand, you can get tangled in that net with no way to get loose to just be yourself.

You’ve written nine novels. Which one was the hardest to write?

My last book [Renato After Alba] was - by far - the hardest to write.

Yes…well, it’s really the only way to do it. I would wait for the students and sit in one of the chairs, usually placed in a circle.

I remember that.

On the first day, they’d walk in and think I was one of the other students. I liked teaching because I like people. And you have to like people, or at least be very interested in them, if you’re going to be a writer.

What did I learn from my students? A pause. In general, you learn about life through your students in the classroom…the way people are...the way they relate. Students are very open. College students are becoming adults, but they’re not totally there yet, which makes it interesting. At the graduate level, they’re mostly there. They’re starting to figure it all out.

Teaching is a wonderful profession, but I like writing even more.

Technology turned the publishing industry on its head. At some point, there will be no one left who remembers the dusty smell of the “old books” section of the library or the card catalogues. How do you feel about all of this?

The publishing industry went through another big change, even before technology took over – a period of consolidation. The publishing houses needed a better way to make money, so they gradually integrated into larger companies with many imprints that specialized in different genres. It was all about their profit/loss sheets. Eventually, there were only a handful of these traditional publishing houses left. The poets were the ones who were really squeezed out during this transformation.

Years ago, independent presses couldn’t get their books reviewed, but that has all changed. Right now, I’m with McPherson & Company [an independent press], and they have a National Book Award winner.*

Of course, in this [digital age], book stores have been really hurt, too. They’ve had to make adjustments – selling postcards, calendars and toys.

*Established in 1950, the National Book Awards are American literary prizes administered by the National Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization. (William Faulkner, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker are among the many notable winners.)

And they’ve added cafes to attract customers – to establish a gathering place to socialize.

Yes. That’s true.

Your Italian heritage comes through in your novels. I would love it if you’d share a fond memory from your childhood that screams Italian upbringing.

Well, I grew up in a house where copies of Dante and Benvenuto Cellini were on the shelf and Italian was spoken in the kitchen.

Thinking back to my childhood, it would probably have to be BIG dinners and BIG holidays – big Christmases, big Easters. For Italians, life is built around the dinner table. On Sundays, my parents, my brother and I would get together with family. I remember when I was young, I had this playmate who told me his family was going to celebrate Thanksgiving with the neighbors. I thought what an emaciated, thin life these people have – to have no relatives. My mother’s mother had nine children, and they all had children, so there were always all these aunts and uncles and cousins. We’d have these huge family gatherings.

But there are two sides to this. Family can be a great safety net. On the other hand, you can get tangled in that net with no way to get loose to just be yourself.

You’ve written nine novels. Which one was the hardest to write?

My last book [Renato After Alba] was - by far - the hardest to write.

|

A few years ago, I attended your book reading in Albany, NY for Renato After Alba, and I remember someone in attendance asked if the book was a memoir. You were adamant that it was not a memoir. When I read it, though, I thought it was too real to NOT be a memoir of sorts. You’ve since said the novel is suffused with your experience of grief after Margaret's death. [In 2010, Gene’s beloved Margaret passed away suddenly at the age of 72.] So, even though the book is not technically a memoir, was the process of writing it healing for you in any way?

When I had finished Renato, the Painter [Gene’s last book before he wrote Renato After Alba], Margaret and I both went to talk to McPherson. [Bruce McPherson is the founder of McPherson & Co.] We knew him – not well at that time – as a guy that owned another independent press.* McPherson wanted to publish it; but then Margaret died. Her death was wholly unexpected, and it ended after some 20 hours or so of torture, agony and terror. I just couldn’t write or even think about it. The whole process was over for me. *Margaret Mirabelli established Spring Harbor, Ltd., an editing/publishing company. |

Did Margaret like Renato, the Painter?

Yes. She always read everything...then criticized very gently - which is written in the marriage contract. (Ha! Margaret would always say that!) She supported everything I did, everything I wrote. And everything I wrote, I wrote for her.

About a year later, McPherson got in touch with me. We went over the manuscript page by page.

[Renato, the Painter was published in May 2012, two years after Margaret’s death.]

Yes. She always read everything...then criticized very gently - which is written in the marriage contract. (Ha! Margaret would always say that!) She supported everything I did, everything I wrote. And everything I wrote, I wrote for her.

About a year later, McPherson got in touch with me. We went over the manuscript page by page.

[Renato, the Painter was published in May 2012, two years after Margaret’s death.]

|

And then…Renato After Alba…

Whenever I would sit down to write, this ‘thing’ would occupy my mind. I realized I had to write this book before I could write another. I realized I had to deal with the grief. I looked back at Renato, and…well…he was a big character, so I knew I could use him easily. I wrote to get it ‘out of the way.’ When I was done, I went to visit my son, Gino. I discovered that I was restless…that I wanted to get out again. I suppose the process itself was healing, but I didn’t realize it at the time. I asked three people, those whose judgment I respected, if the book was for the public – my daughter Francesca [an editor], a dear friend, and another writer whom I admired. They all said it should be published. |

Renato did not lose his sense of humor. Is humor the thing that ultimately gets us through to the other side of grief?

It was extremely important to write a book that was not depressing.

But I don’t know what ultimately gets us through. It’s probably different for everyone. Even though you feel like you want to die…you don’t. I distinctly remember driving to the grocery store one day, and I just slammed my palms into the steering wheel. I thought, ‘Enough! I’ll go on.’

Renato says, “The gods have given us love instead of immortality.” Is love immortal?

I can say this: I never doubted how fortunate I was - more fortunate than any person I knew – to have Margaret in my life…to have that kind of relationship. When I look around, I realize it’s a rare thing to have what we had.

As to the gods [in Greek mythology]…they kept immortality to themselves, but they gave humans love instead. Even though we eventually die, love is that thing that remains - it’s uniquely human and powerful.

Do you have plans to write another novel?

I’ve already begun another book. I didn’t want my books to end with Renato After Alba. At the time, I thought that Renato, the Painter was my last one.

But then I think of Yeats’s “The Tower”* He wrote his best poetry when he was much older, when he was full of what he wanted to do and say and write. What is this thing that “has been tied to me…?”

I’m just not sure where to go with it right now. With this pandemic, who knows what the world will look like?

*“The Tower” is the second poem in William Butler Yeats’s The Tower (1928), his first major collection of poems as Nobel Laureate after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1923.

What are you most proud of?

My family. My family has always been the center of all things. If you don’t have your family, what do you have?

It was extremely important to write a book that was not depressing.

But I don’t know what ultimately gets us through. It’s probably different for everyone. Even though you feel like you want to die…you don’t. I distinctly remember driving to the grocery store one day, and I just slammed my palms into the steering wheel. I thought, ‘Enough! I’ll go on.’

Renato says, “The gods have given us love instead of immortality.” Is love immortal?

I can say this: I never doubted how fortunate I was - more fortunate than any person I knew – to have Margaret in my life…to have that kind of relationship. When I look around, I realize it’s a rare thing to have what we had.

As to the gods [in Greek mythology]…they kept immortality to themselves, but they gave humans love instead. Even though we eventually die, love is that thing that remains - it’s uniquely human and powerful.

Do you have plans to write another novel?

I’ve already begun another book. I didn’t want my books to end with Renato After Alba. At the time, I thought that Renato, the Painter was my last one.

But then I think of Yeats’s “The Tower”* He wrote his best poetry when he was much older, when he was full of what he wanted to do and say and write. What is this thing that “has been tied to me…?”

I’m just not sure where to go with it right now. With this pandemic, who knows what the world will look like?

*“The Tower” is the second poem in William Butler Yeats’s The Tower (1928), his first major collection of poems as Nobel Laureate after receiving the Nobel Prize in 1923.

What are you most proud of?

My family. My family has always been the center of all things. If you don’t have your family, what do you have?

|

Plans are for the above three novels to be published together in one volume

later this year by McPherson & Company. |

More of Gene's writing can be found here:

"My novels, beginning with The World at Noon, are connected through characters who are friends of or - more often - are members of the Stillamare or Cavallu families. What the publisher has done is gathered the three recent novels together. These three are narrated by Renato. The first, The Goddess in Love with a Horse, is a sort of genealogical history of the family, the second, Renato the Painter, is (mostly) a story of Renato's 70th year, and the third, Renato After Alba - which, of course, I had never planned to write - is Renato after the death of his wife, Alba. My books sometimes have characters inspired by real people, but none are memoirs." ~ Gene Mirabelli |