May 2022 Featured Artist

Artist's Work Exudes Soulful Aura

and Blends Contrasting Styles to Initiate Conversations

An Interview with Acclaimed, Contemporary Figurative Artist

Patricia Watwood

|

Patricia Poses with 'The Sixth Extinction'

Oil on Linen ~ 67 ½ x 51 ½” inches Photo Credit: Benjamin Chasteen |

Patricia Watwood is a leading figure in the contemporary figurative movement. Her subjects are primarily women and figures, incorporating myth and narrative. She has exhibited at the Beijing World Art Museum, The European Museum of Modern Art (MEAM), and The Butler Museum. Her work is included in the collections of the St. Louis University Museum of Art and the New Britain Museum of American Art. Her commissioned portraits hang in institutions, such as St. Louis City Hall, Washington University, Kennedy School of Government, and at the Harvard Art Museums.

Patricia is a member of the Salmagundi Club of New York, where she is the current First Vice President (2021). She is also a Signature member of the Portrait Society of America and was named a Living Master by the Art Renewal Center. She is represented by Portraits Inc., Dacia Gallery, and others. Patricia earned her M.F.A .with honors from New York Academy of Art and studied with Jacob Collins as a founding member of the Water Street Atelier. She has produced instructional DVDs, including “Creating Portraits from Life” with Streamline Art Video, and has been a professor of drawing at New York Academy of Art. She has created several online drawing courses, including Seven Days of Drawing with the creative streaming platform Craftsy.com. She has written articles for American Artist, American Arts Quarterly, and Fine Art Connoisseur magazines and teaches painting in Brooklyn, online with Terracotta.org, and in workshops around the country. Her first book, The Path of Drawing (Monacelli Studio Press) will be released in late 2022. |

|

“Patricia Watwood is at the forefront of today's classical painting scene. Her work portrays the female figure not only as beautiful but also as intellectual and spiritual. Her allegorical compositions combine a modern color palette with classical painting techniques with the intention of reinstating the role of beauty in art.” ~ Brandon Kralik, post contemporary painter and former HuffPost contributor |

Myrna Beth Haskell, executive editor, spoke with Patricia about her process and inspirations which led to an in-depth discussion about several of her pieces.

I’d love to discuss the otherworldly/mystical themes throughout much of your work.

It’s been a bit of a long evolution for me in discovering and shaping my subject matter. Since a young age, I’ve had a strong interest in spirituality and religion. I am an elder at a Presbyterian church which is a very active part of my life. I’ve also studied world religions, transcendental poetry, mysticism, and I’ve participated in Zen meditation boot camps. So, my spiritual experience is very broad. I think of my art as a gift or a call – that God has given me this talent and has called me in this direction. So, these two things [my art and my spirituality] that I once thought of as separate have intermingled a lot more.

I’d love to discuss the otherworldly/mystical themes throughout much of your work.

It’s been a bit of a long evolution for me in discovering and shaping my subject matter. Since a young age, I’ve had a strong interest in spirituality and religion. I am an elder at a Presbyterian church which is a very active part of my life. I’ve also studied world religions, transcendental poetry, mysticism, and I’ve participated in Zen meditation boot camps. So, my spiritual experience is very broad. I think of my art as a gift or a call – that God has given me this talent and has called me in this direction. So, these two things [my art and my spirituality] that I once thought of as separate have intermingled a lot more.

|

Most of the art of the past, especially works that were part of the Western canon, were often created by people commissioned by the church or by those woven into a culture with the [prevailing] idea that there is a God, and you have a soul. A lot of early art makers may not have thought of themselves as artists, but they likely held roles as priests or priestesses (apparent through the study of ancient Egyptian cultures and ancient cave paintings). Today, we’re in a very secular age, and the art world is a very secular place. It’s not one that asks, ‘Do you have a soul?’

For me, portraiture isn’t about conveying how someone looks. Instead, I want to convey how the person feels, his or her presence – which goes beyond something external. When I see a Rembrandt, it can make me cry because I feel the work has a soul – and that’s magical! |

"For me, portraiture isn’t about conveying how someone looks. Instead, I want to convey how the person feels, his or her presence – which goes beyond something external. When I see a Rembrandt, it can make me cry because I feel the work has a soul – and that’s magical!" ~ Patricia Watwood |

Another way to look at this is the idea that art is a reservoir of auratic energy – it has an aura. We as artists use our literal energy to make a [work]. Really great art becomes a matrix for this energy that can be received by other people, even hundreds of years later.

Your piece ‘Icarus’ is stunning and thought-provoking. What was the inspiration?

That’s definitely one of my favorite paintings. It helped me understand that I love to use myth and narrative because of how it is a touchpoint of communication between myself and my viewer. You probably already have in your mind some ideas of what the story of Icarus is about and what it means. I look to use those touchpoints as a way to build a bridge about what’s happening in this painting and why.

Your piece ‘Icarus’ is stunning and thought-provoking. What was the inspiration?

That’s definitely one of my favorite paintings. It helped me understand that I love to use myth and narrative because of how it is a touchpoint of communication between myself and my viewer. You probably already have in your mind some ideas of what the story of Icarus is about and what it means. I look to use those touchpoints as a way to build a bridge about what’s happening in this painting and why.

Icarus

Oil on Linen ~ 26 x 36 inches

© Patricia Watwood

Oil on Linen ~ 26 x 36 inches

© Patricia Watwood

|

|

Patricia shares a preparatory sketch of the original pose the model created as well as another early study of the work. I often have an idea kicking around in my head, but this time my idea came from [the spontaneous pose the model settled into]. Certain narratives emerge because of how they resonate with what’s going on in my personal life. I created this painting during a time in my life when all the sh-t hit the fan…a really difficult time for me. With the story of Icarus, you often hear the catch phrase, ‘Don’t fly too close to the sun.’ Icarus is a cautionary tale. This is the wrong message for everyone but particularly for women. We all want to fly. It’s human nature to explore. I see this story as a cycle we all go through where we ambitiously strive for new things – we fail, we crash...then what do we do? |

It's also important to note that the model is a woman. I mostly paint women because I’m interested in women’s stories. In our patriarchal society, many of our hero stories are about men. I find that the people who have the most enthusiastic reactions – those who really understand what I’m doing and relate to my work – are women.

While examining ‘Icarus,’ I felt that the blood didn't distract from what I was initially drawn to – her beauty. Instead, it encouraged a lengthy contemplation of the piece.

I really appreciate your comment because this makes me think about how do I construct a good painting? The very first thing a viewer needs to see is the aesthetic – the beauty, the composition. [My purpose] is to draw the viewer from across the room to take a closer look. Once viewers are really drawn in, they can start to unpack. I want a general audience to visually think of my paintings as striking and beautiful to start the conversation.

While examining ‘Icarus,’ I felt that the blood didn't distract from what I was initially drawn to – her beauty. Instead, it encouraged a lengthy contemplation of the piece.

I really appreciate your comment because this makes me think about how do I construct a good painting? The very first thing a viewer needs to see is the aesthetic – the beauty, the composition. [My purpose] is to draw the viewer from across the room to take a closer look. Once viewers are really drawn in, they can start to unpack. I want a general audience to visually think of my paintings as striking and beautiful to start the conversation.

|

Let’s talk about “Suzannah in the Moonlight” and your choice of color.

In part, it started as just an exploration of color. A lot of historical figurative work is often very tonalist – a range of browns. In contemporary figurative work, there’s a synthesis of old-fashioned, traditional figurative drawing with a very modern, broad palette of colors. I wanted to explore painting a figure that is not in a ‘normal’ lighting condition. I wanted to make a cool, nocturnal light effect, but I also wanted to make sure it was interpreted as a skin tone in a blue light as opposed to a blue person. I’m interested in how our brains interpret lighting and color. Everything I do is an exploration of light and shadow, and I’ve become more conscious about my palette choice. This painting is based on the biblical narrative of ‘Susanna and the Elders’ which tells the story of the elders who spy on young Susanna in the garden. I also created this in the middle of the #MeToo movement. It’s representational of my very complicated relationship to the beautiful woman. I am a woman artist using a woman’s naked beauty to make a point. But as a woman artist, I’m on her side. I am interested in her agency and safety. I want the painting to elicit a conversation about a host of questions: Who possesses the beauty? Who looks at the beauty? Who wants the beauty? Have you always used the juxtaposition of realistic, representational work with a more impressionistic approach to backgrounds? This is something I’ve been doing more and more. I love art that has a broad dynamic range – parts that are really tight and carefully rendered juxtaposed with parts that are messy and splashy. |

Suzannah in the Moonlight

Oil on Linen ~ 44 x 34 inches © Patricia Watwood |

|

Rachel, Moonlight Study

Oil on Linen ~ 22 x 17 inches © Patricia Watwood |

I grew up at a time when you trained by painting modern life and using observation to create figurative work that was realistic (or a type of documentary). But I’m increasingly interested in painting something that is a work of fiction. I paint a model from life, but the rest is invention. I’m more interested in imagination. I also really enjoy the illusion of detail – using paint strokes and textures that convey realism from a distance, but the painting dissolves into something else when you see it up close. I play with the boundaries, too – blending the background with the figure. I also think a lot about the idea of a ‘willing suspension of disbelief;’ however, every fictional universe has its rules. In Harry Potter, for instance, there can be skeletal flying horses which are accepted as part of that world, but if Harry Potter pulled out a cell phone, you would say, ‘Wait! That doesn’t fit!’ I’m trying to get the viewer to accept an outlandish image. The work can’t be too realistic, or the viewer won’t accept it. So, I’m using more painterly elements and slightly exaggerated color for the viewer to realize the work is not a documentary. I want the viewer to accept the terms as I’ve presented them, so we can have a conversation about what the story means.

|

Tell me about your manipulation of light and how this helps to present the incredible depth in your pieces.

|

I absolutely love pictorial space – using layers to create the illusion of deep space. I pay careful attention to overlaps and use atmospheric perspective, creating more contrast in the things that are close as opposed to a receding quality of those things in the distance. There are a lot of tools an artist can use to develop that sense of pictorial space.

Do you do a lot of planning for a piece, or does your work take you in directions that surprise you? The planning happens in two different ways. ‘Icarus’ is the most extreme example where the painting emerged from an idea I had after I saw the model’s impromptu pose. But sometimes I have an idea ahead of time. This was true with my piece ‘Pandora.’ In this case, there was a lot of planning with several studies and work on different compositions. I was thinking about Pandora’s Box – of course, she is going to open the box! I had an idea ahead of time for a pose. This piece is also a [commentary on the attacks of] September 11 [and other threats to society] – an airplane and the two towers appear in the background. The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster happened while I was painting ‘Pandora’ (in 2011). The figure’s hand gesture represents dismay – what is this world? The last thing left in the box is ‘hope,’ represented by an Eastern Bluebird which was once endangered but had a comeback. |

Pandora

Oil on Linen ~ 32 x 28 inches © Patricia Watwood |

Let's talk about the juxtaposition of natural and technological elements in "Sleeping Venus' and other works.

'Sleeping Venus' was done in the same period as ‘Pandora.’ Themes of environmentalism are increasingly important to me as this issue becomes more urgent. It’s also a conversation about intrinsic value.

In the 20th century, the female nude (female beauty) was rejected as a legitimate subject. We got Willem de Kooning instead (1904 – 1997). I was exploring ideas such as ‘What do we spend our money on?’ An iPhone might cost $1300, but three years later its value has significantly decreased.

'Sleeping Venus' was done in the same period as ‘Pandora.’ Themes of environmentalism are increasingly important to me as this issue becomes more urgent. It’s also a conversation about intrinsic value.

In the 20th century, the female nude (female beauty) was rejected as a legitimate subject. We got Willem de Kooning instead (1904 – 1997). I was exploring ideas such as ‘What do we spend our money on?’ An iPhone might cost $1300, but three years later its value has significantly decreased.

Wendy Steiner’s Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in 20th Century Art was a useful book for me. The female figure here is among the garbage – thrown out with other things. The canary is trying to wake up Venus [representative of the ‘canary in a coal mine’ metaphor – an early warning of trouble or danger]. To explore the theme of environmentalism, the natural elements are also rejected and imperiled.

Even the frame exists as a commentary on intrinsic value versus perceived value.

In the 19th century, those who owned expensive art would use elaborate, gilded gold frames to [exemplify the artwork’s value]. Contemporary art rejects these types of frames. The frame I’ve created connects to what’s literally in the painting. Pieces of electronics, U.S. dollars, Chinese currency, etc., are glued or screwed on. It gives the impression of a beautiful mosaic. It’s a complicated meditation on what we value. [See Venus Apocalypse Frames]

Even the frame exists as a commentary on intrinsic value versus perceived value.

In the 19th century, those who owned expensive art would use elaborate, gilded gold frames to [exemplify the artwork’s value]. Contemporary art rejects these types of frames. The frame I’ve created connects to what’s literally in the painting. Pieces of electronics, U.S. dollars, Chinese currency, etc., are glued or screwed on. It gives the impression of a beautiful mosaic. It’s a complicated meditation on what we value. [See Venus Apocalypse Frames]

|

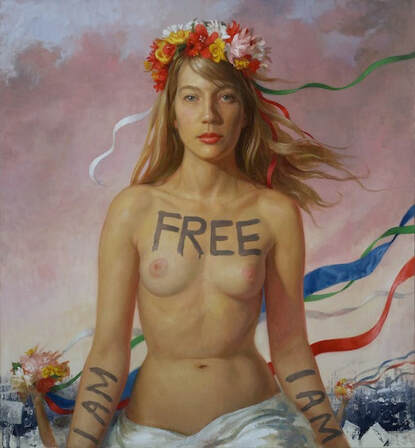

Femen Flora

Oil on Linen ~ 28 x 26 inches © Patricia Watwood |

Your commissioned portraits truly capture a client's mood and personality. What is it you look for in the human face that helps you to paint beyond a skin-deep perspective?

This is a focus when I’m creating a portrait. Is there a sense of presence? There are a million subtle things with expression and gestures in the body. How are the shoulders set? How composed is the model? When I’m able to work from life and connect in person with clients, it is the easiest way for me to get a sense of who they really are. However, I’ve also created a number of posthumous projects. In these cases, I try to talk to family members and look at a lot of different pictures of them. Then, I use my imagination and intuition. Where do you find sanctuary?

I find sanctuary in drawing and in my creative practice. Drawing is my regular touchstone to keep myself anchored in whatever it is I’m doing as an artist. You sit very quietly when you draw. You can connect to that still, quiet voice in your own mind that’s trying to be heard but can’t get out. |

|

ONLINE CLASS

Classical Figure Drawing II Mondays ~ 6:00 p.m to 9:00 p.m. (EST)

Through June 27 Participants will learn classical principles for drawing the human form. You will study various approaches that build skills in accurate and aesthetic figure drawing. This course will deepen your understanding of modeling form, the effects of light, and human structure, learning from a figurative master.

|

Photo Credit: Stefan Hagen

|

UPCOMING PUBLICATION

To be excerpted in Sanctuary in December 2022 The Path of Drawing:

Lessons in Everyday Creativity and Mindfulness (Monacelli Studio Press) Planned Release: November 2022 This is an art instructional book on cultivating creativity and drawing as a practice of mindfulness. It guides readers to cultivate a creative practice, learn skills in realistic drawing, and developing confidence in one’s individual voice. The book focuses on aspects of mindfulness as particularly relevant to creative individuals, like overcoming blocks and common emotional challenges to accomplishing work, and build a personal source of inspiration and imagination. It also illustrates the ways in which artists use drawing as a vehicle for exploring ideas and developing complex works. |