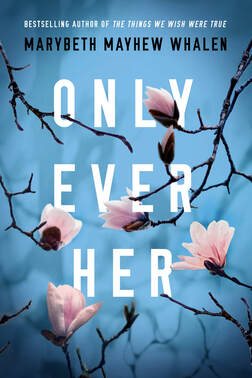

Play & Book Excerpts

Only Ever Her

(Lake Union Publishing.)

© 2019 Marybeth Mayhew Whalen

Though she has made it as far as parking outside the lawyer’s office, she finds herself unable to go in. She has her fingers around the door handle, ready to tug it open at any moment. The car is new, so the door won’t creak loudly when she opens it like her old car did. (Ah, the Jetta, may she rest in peace.) This SUV, a pristine, mature vehicle choice, will not give her any problems. Like her fiancé, Scott, who selected and bought her the Honda CR-V as an early wedding gift, this car is new and reliable and suitable for starting her new life in a few weeks as Mrs. Annie Hanson.

She lets go of the door handle and glances down at the letter on her lap, sees her name in the salutation just above the fold, her name as it is now: Ms. Annie Taft. She is not Annie Hanson yet. She has things she must do before that can happen. And showing up for a meeting at this attorney’s office is one of those things.

She looks at the building just in front of her, a two-story redbrick colonial-style office that could house any sort of business at all—an insurance agency or dental practice or accounting firm. She scans the numerous windows as if someone might be watching her out of one of them. But there are no faces framed in the windowpanes, no pairs of eyes peeking through the blinds. No one is even aware she is here.

She didn’t call to make an appointment, even though the letter had suggested she do so. She wanted no guarantee the attorney would have time for her. All the better if he told her to come back and then she just never did. She’s going to be very busy in the coming days, after all. She will scarcely have time for anything besides preparing for her wedding. Then she can tell herself—and anyone else—that she tried. She can say she did the right thing. Annie cares very much about doing the right thing; it is a part of who she is.

But what is the right thing? That is the question.

In her head, her aunt Faye starts to speak, reiterating what she, Faye, thinks is the right thing. (Which is not what Annie is now doing, for the record.) Some people hear their mother’s voices in their heads, but Annie hears her aunt’s, the closest thing she has to a mother. Annie quiets Aunt Faye’s disapproving voice by distracting herself. She checks her makeup in the visor mirror, smiling to make sure there isn’t any lipstick on her teeth. There’s nothing on her teeth, but she sees that she could use a touch-up. She’s chewed at her bottom lip so much that the lipstick she applied this morning is mostly gone.

She gets out her cosmetic bag from her purse and plunks it right on top of the letter, hiding it from sight. She pulls out her favorite lipstick and reapplies a swath of berry stain across her bow of a mouth. (She has her mother’s smile, everyone says. Based on the photos she’s seen, this is true.) Then, just for good measure, she touches up her nose with fresh powder. The early-summer heat is making her shiny, and sitting in this car isn’t helping.

She should just get out and go inside. Pull the trigger, rip off the Band-Aid, as they say. But then she notices her eyebrows—the bright sunlight reveals some stray hairs that need to be plucked. She pulls tweezers from the cosmetic bag and removes the offensive hairs. It’s always good to look your best when meeting anyone new, she reasons, and this attorney is someone new. He is a total stranger who has barged into her life uninvited through this letter he sent to her, presuming more about her than she is capable of.

Dear Ms. Taft,

I am writing to deliver some news about my client, Mr. Cordell Lewis, a man I believe was unfairly sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole after being wrongfully convicted of the death of your mother, Lydia Taft. As a witness—and a key part of the prosecution’s case against him—Ms. Taft, I understand that for you this story is a part of your past, but it is far from that for Mr. Lewis. It’s very much in the present, and to any hope he has for a future.

I would appreciate it if you could come in to my office for a short meeting to allow me to inform you face-to-face of some new developments in the case as well as ask for one small favor. I look forward to meeting with you at your earliest convenience, as time is of the essence. Please know that, as the information I will be passing along to you is sensitive in nature, this meeting will need to be strictly confidential. Again, I will look forward to hearing from you and to sharing with you the exciting things that are happening.

Thank you for your time,

Tyson Barnes

It is a short letter—not a lot to it, really—but long enough to levy enough guilt at her to bring her here for this meeting, to talk about doing “a small favor” for the man she’s grown up believing murdered her mother. But what if he didn’t? Her stupid conscience keeps asking this one unending question. One she has to entertain before she can start a life of her own, a life away from here. That is part of her plan with Scott: get married, move somewhere else, start fresh. At the time they devised it, it sounded like a good plan. But the closer she gets to leaving, the more she wonders if she can.

She inspects her face one final time before flipping the visor back into place and stowing her cosmetic bag in her purse. Her stomach rumbles, and she thinks about her lunch appointment—another thing she doesn’t want to do but feels obligated to show up for. If she isn’t careful, she’s going to be late for that. If the attorney is in and does want to talk, she might miss it altogether. She can’t decide which would be worse: talking to the attorney who is trying to get Cordell Lewis, the man currently in prison for her mother’s murder, released or showing up for an interview with a reporter from the town paper to talk about her wedding.

Annie is certain the reporter will find a way to also ask about Cordell Lewis’s upcoming hearing. She suspects that this is what the reporter really wants to talk about, that this interview is just subterfuge. She and Laurel, the reporter, went to high school together. Laurel was always the aggressive type, and Annie doubts she’s changed much in the eight years since graduation. If anything, her years away from Ludlow working for larger papers has probably made her more relentless. Lewis’s release is a bigger story than Annie’s wedding, after all. Annie wouldn’t put it past Laurel to pull something like that. She will be on her guard.

She makes her decision and turns off the car, deciding that she will do what she came here to do, selecting the lesser of the two evils. She will go in and talk to—she looks down at the letter again to double-check the name of the man she has come here to see. She reads the signature line, imagines telling the receptionist that she is there to see Tyson Barnes. The receptionist will either say, “Oh yes, he’s been expecting you. Right this way!” Or she will say, “I’m so sorry, but he’s in court. Would you like me to let him know you stopped by?”

Whatever the outcome, Annie must go through with this. She must go and hear what this attorney has to say about Cordell Lewis, who has spent the last twenty-three years in prison for killing her mother. According to his letter, Tyson Barnes thinks that Cordell Lewis is innocent. He thinks he was wrongly convicted all those years ago and that Annie was part of the witch hunt that made the wrongful conviction stick. He wants to talk about what she can do now, as a twenty-six-year-old woman, to make up for what she did as a three-year-old child. He thinks she can help set things right.

Annie knows one thing: nothing can set things right. No matter what she does or does not do, her mother will not be there when she walks down the aisle in a matter of days. Her mother will not wear a mother-of-the-bride dress that is slightly dowdy but appropriate for the occasion. She will not give Annie a family heirloom to be her “something blue.” She will not offer marriage advice based on her own years of wisdom. Because Annie’s mother did not have years to grow wise. Lydia Taft died when she was twenty-three years old. She didn’t even get to live as long as Annie herself has.

“Okay, Tyson Barnes,” Annie says aloud in the car. “You’ve got fifteen minutes. And that’s all you get.” Then she opens the car door and steps out.

She lets go of the door handle and glances down at the letter on her lap, sees her name in the salutation just above the fold, her name as it is now: Ms. Annie Taft. She is not Annie Hanson yet. She has things she must do before that can happen. And showing up for a meeting at this attorney’s office is one of those things.

She looks at the building just in front of her, a two-story redbrick colonial-style office that could house any sort of business at all—an insurance agency or dental practice or accounting firm. She scans the numerous windows as if someone might be watching her out of one of them. But there are no faces framed in the windowpanes, no pairs of eyes peeking through the blinds. No one is even aware she is here.

She didn’t call to make an appointment, even though the letter had suggested she do so. She wanted no guarantee the attorney would have time for her. All the better if he told her to come back and then she just never did. She’s going to be very busy in the coming days, after all. She will scarcely have time for anything besides preparing for her wedding. Then she can tell herself—and anyone else—that she tried. She can say she did the right thing. Annie cares very much about doing the right thing; it is a part of who she is.

But what is the right thing? That is the question.

In her head, her aunt Faye starts to speak, reiterating what she, Faye, thinks is the right thing. (Which is not what Annie is now doing, for the record.) Some people hear their mother’s voices in their heads, but Annie hears her aunt’s, the closest thing she has to a mother. Annie quiets Aunt Faye’s disapproving voice by distracting herself. She checks her makeup in the visor mirror, smiling to make sure there isn’t any lipstick on her teeth. There’s nothing on her teeth, but she sees that she could use a touch-up. She’s chewed at her bottom lip so much that the lipstick she applied this morning is mostly gone.

She gets out her cosmetic bag from her purse and plunks it right on top of the letter, hiding it from sight. She pulls out her favorite lipstick and reapplies a swath of berry stain across her bow of a mouth. (She has her mother’s smile, everyone says. Based on the photos she’s seen, this is true.) Then, just for good measure, she touches up her nose with fresh powder. The early-summer heat is making her shiny, and sitting in this car isn’t helping.

She should just get out and go inside. Pull the trigger, rip off the Band-Aid, as they say. But then she notices her eyebrows—the bright sunlight reveals some stray hairs that need to be plucked. She pulls tweezers from the cosmetic bag and removes the offensive hairs. It’s always good to look your best when meeting anyone new, she reasons, and this attorney is someone new. He is a total stranger who has barged into her life uninvited through this letter he sent to her, presuming more about her than she is capable of.

Dear Ms. Taft,

I am writing to deliver some news about my client, Mr. Cordell Lewis, a man I believe was unfairly sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole after being wrongfully convicted of the death of your mother, Lydia Taft. As a witness—and a key part of the prosecution’s case against him—Ms. Taft, I understand that for you this story is a part of your past, but it is far from that for Mr. Lewis. It’s very much in the present, and to any hope he has for a future.

I would appreciate it if you could come in to my office for a short meeting to allow me to inform you face-to-face of some new developments in the case as well as ask for one small favor. I look forward to meeting with you at your earliest convenience, as time is of the essence. Please know that, as the information I will be passing along to you is sensitive in nature, this meeting will need to be strictly confidential. Again, I will look forward to hearing from you and to sharing with you the exciting things that are happening.

Thank you for your time,

Tyson Barnes

It is a short letter—not a lot to it, really—but long enough to levy enough guilt at her to bring her here for this meeting, to talk about doing “a small favor” for the man she’s grown up believing murdered her mother. But what if he didn’t? Her stupid conscience keeps asking this one unending question. One she has to entertain before she can start a life of her own, a life away from here. That is part of her plan with Scott: get married, move somewhere else, start fresh. At the time they devised it, it sounded like a good plan. But the closer she gets to leaving, the more she wonders if she can.

She inspects her face one final time before flipping the visor back into place and stowing her cosmetic bag in her purse. Her stomach rumbles, and she thinks about her lunch appointment—another thing she doesn’t want to do but feels obligated to show up for. If she isn’t careful, she’s going to be late for that. If the attorney is in and does want to talk, she might miss it altogether. She can’t decide which would be worse: talking to the attorney who is trying to get Cordell Lewis, the man currently in prison for her mother’s murder, released or showing up for an interview with a reporter from the town paper to talk about her wedding.

Annie is certain the reporter will find a way to also ask about Cordell Lewis’s upcoming hearing. She suspects that this is what the reporter really wants to talk about, that this interview is just subterfuge. She and Laurel, the reporter, went to high school together. Laurel was always the aggressive type, and Annie doubts she’s changed much in the eight years since graduation. If anything, her years away from Ludlow working for larger papers has probably made her more relentless. Lewis’s release is a bigger story than Annie’s wedding, after all. Annie wouldn’t put it past Laurel to pull something like that. She will be on her guard.

She makes her decision and turns off the car, deciding that she will do what she came here to do, selecting the lesser of the two evils. She will go in and talk to—she looks down at the letter again to double-check the name of the man she has come here to see. She reads the signature line, imagines telling the receptionist that she is there to see Tyson Barnes. The receptionist will either say, “Oh yes, he’s been expecting you. Right this way!” Or she will say, “I’m so sorry, but he’s in court. Would you like me to let him know you stopped by?”

Whatever the outcome, Annie must go through with this. She must go and hear what this attorney has to say about Cordell Lewis, who has spent the last twenty-three years in prison for killing her mother. According to his letter, Tyson Barnes thinks that Cordell Lewis is innocent. He thinks he was wrongly convicted all those years ago and that Annie was part of the witch hunt that made the wrongful conviction stick. He wants to talk about what she can do now, as a twenty-six-year-old woman, to make up for what she did as a three-year-old child. He thinks she can help set things right.

Annie knows one thing: nothing can set things right. No matter what she does or does not do, her mother will not be there when she walks down the aisle in a matter of days. Her mother will not wear a mother-of-the-bride dress that is slightly dowdy but appropriate for the occasion. She will not give Annie a family heirloom to be her “something blue.” She will not offer marriage advice based on her own years of wisdom. Because Annie’s mother did not have years to grow wise. Lydia Taft died when she was twenty-three years old. She didn’t even get to live as long as Annie herself has.

“Okay, Tyson Barnes,” Annie says aloud in the car. “You’ve got fifteen minutes. And that’s all you get.” Then she opens the car door and steps out.

|

Photo Credit: Portrait Innovations

|

Marybeth Mayhew Whalen is the author of When We Were Worthy, The Things We Wish Were True, and five previous novels. She is the co-founder of the popular women's fiction site, She Reads, and speaks to women's groups around the country.

Marybeth and her husband Curt have been married for 26 years and are the parents of six children, ranging from young adult to elementary age. The family lives in North Carolina. Marybeth spends most of her time in the grocery store but occasionally escapes long enough to scribble some words. She is always at work on her next novel. |