Play & Book Excerpts

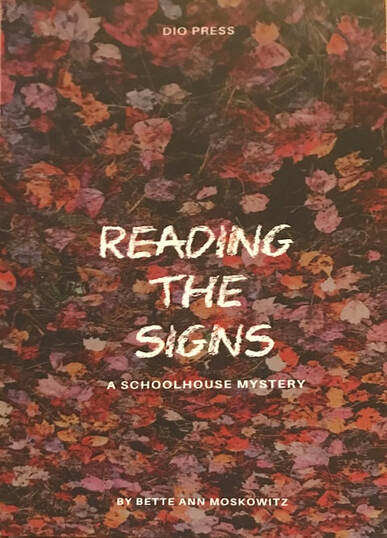

Reading the Signs

A Schoolhouse Mystery

(DIO Press Inc.)

Bette Ann Moskowitz

PROLOGUE: The Text

One undetonated Tuesday, a woman was idly peering through her binoculars at the comings and goings of herring gulls, when she spied movement behind a sand dune. An unfamiliar land-creature, she thought. The land creature came into full view. A woman. And from the same dune, another land creature appeared. A man. The watching woman saw them walking, a little space between them, and when they got beyond the houses, near the jetty, the man turned to the woman and spoke and gestured, so the watching woman imagined she heard, Do you want to stop here? In his question was desire.

The watching woman could read the desire in the set of his shoulders, the tilt of his head. And the other one got it, too. Brushing sand from her hand, she scraped her red nails against his arm. The watching woman could see him tremble. The woman stumbled and fell against him as if by accident. He grasped her by the waist as if to steady her, but she fell further, full against him. His hand foraged under her white, man-tailored shirt and they both fell together, and sank behind the dune. Gasping. The watching woman thought the gasp. The watching woman thought his hands covered the small breasts, and she was momentarily set afire by the thought. She imagined he said, Let me, and the woman brought his finger to her mouth and bit on it, acting out a passion she was beginning to feel. The watching woman imagined he went off like a shot, too fast, with his hand still where the woman put it, and the other hand covering her face, and the woman looked through his fingers up, above her, out at the water, over the sands and she said, with rising passion, I think someone is watching us.

THERE IS NOTHING YOU CANNOT DECODE

if you read carefully enough, if you apply your mind.

–Sylvie Fried, Reading Specialist, Teacher Magazine

One undetonated Tuesday, a woman was idly peering through her binoculars at the comings and goings of herring gulls, when she spied movement behind a sand dune. An unfamiliar land-creature, she thought. The land creature came into full view. A woman. And from the same dune, another land creature appeared. A man. The watching woman saw them walking, a little space between them, and when they got beyond the houses, near the jetty, the man turned to the woman and spoke and gestured, so the watching woman imagined she heard, Do you want to stop here? In his question was desire.

The watching woman could read the desire in the set of his shoulders, the tilt of his head. And the other one got it, too. Brushing sand from her hand, she scraped her red nails against his arm. The watching woman could see him tremble. The woman stumbled and fell against him as if by accident. He grasped her by the waist as if to steady her, but she fell further, full against him. His hand foraged under her white, man-tailored shirt and they both fell together, and sank behind the dune. Gasping. The watching woman thought the gasp. The watching woman thought his hands covered the small breasts, and she was momentarily set afire by the thought. She imagined he said, Let me, and the woman brought his finger to her mouth and bit on it, acting out a passion she was beginning to feel. The watching woman imagined he went off like a shot, too fast, with his hand still where the woman put it, and the other hand covering her face, and the woman looked through his fingers up, above her, out at the water, over the sands and she said, with rising passion, I think someone is watching us.

THERE IS NOTHING YOU CANNOT DECODE

if you read carefully enough, if you apply your mind.

–Sylvie Fried, Reading Specialist, Teacher Magazine

CHAPTER 1: Inventory

Summer ends in Rose Beach, New York. Tides shift. Canada geese fly. Summer people depart. Beach grass is so tall it can hide bodies. The Swimsuit Center reopens next week as Sweater Circus.

It is the first day of school. Children walk along Beach Street to the schoolyard in twos and threes. A whistle blows. They line up slowly.

Sylvie Fried, the remedial reading teacher, watches from her second-floor window as they march, two by two, their hearts in their shoes, she knows, to school. She used to get choked up at the sight of them, so sad and freshly clean.

They march past the lone tree in the schoolyard. The tree’s trunk, where it meets the earth, is like a hippopotamus' foot, except one toe comes out a little further, like an anthropological forerunner. The tree is old and its bark is like rough hide, with long vertical cracks. Children straddle it, or poke between its toes with sticks as if it is a tame and friendly creature.

Hanging on a low branch is a rope left over from last spring. During recess, children will swing on it, and no matter how many times the principal removes the rope, someone always puts one back, and children are always swinging on it. Which is the reason the tree is on the district removal list.

They talk about it in the Teachers Room. Someone says, "What if a child gets injured? We’ll be liable."

Sylvie defends the tree. “In all the years no one has ever gotten hurt. Kids fall off the playground swings all the time. So why don’t you outlaw the swings?”

“Oh, Sylvie,” someone else says. “Come on.”

“Isn't part of being a kid swinging and falling off?”

Apparently not if it leaves the teachers vulnerable to legal action.

Lorna, who teaches the top sixth grade: “Anyway, it’s too close to the brick wall. A kid could end up smashing his head like an apple.”

“So tie a tire to the end of it. It’ll make a great swing.”

"What is this, someone's backyard?" Marla Frost snaps.

She directs her comment to the light fixture above them, to demonstrate that she is not talking to Sylvie.

They have been on the outs since Marla accused Sylvie of assigning an inappropriate book to one of her 6th graders because the cover showed a woman with big breasts. She made a federal case out of it, even calling the boy's parents, though Sylvie explained the book itself was fine, vocabulary and cognition level high, and she was just using the cover as a lure for the pre-teen. And it had worked. He passed. That’s what bothers Marla the most, Sylvie thinks.

Sylvie has always been the loyal opposition in the Teachers Room, the resident free spirit. She used to feel she was there to remind her fellow teachers to love the children as they correct them, and to lighten up when the job got serious. But, lately, her heart isn’t in it. Abruptly tired of the argument, she finishes her coffee, tosses the rest of her bagel and leaves.

Summer ends in Rose Beach, New York. Tides shift. Canada geese fly. Summer people depart. Beach grass is so tall it can hide bodies. The Swimsuit Center reopens next week as Sweater Circus.

It is the first day of school. Children walk along Beach Street to the schoolyard in twos and threes. A whistle blows. They line up slowly.

Sylvie Fried, the remedial reading teacher, watches from her second-floor window as they march, two by two, their hearts in their shoes, she knows, to school. She used to get choked up at the sight of them, so sad and freshly clean.

They march past the lone tree in the schoolyard. The tree’s trunk, where it meets the earth, is like a hippopotamus' foot, except one toe comes out a little further, like an anthropological forerunner. The tree is old and its bark is like rough hide, with long vertical cracks. Children straddle it, or poke between its toes with sticks as if it is a tame and friendly creature.

Hanging on a low branch is a rope left over from last spring. During recess, children will swing on it, and no matter how many times the principal removes the rope, someone always puts one back, and children are always swinging on it. Which is the reason the tree is on the district removal list.

They talk about it in the Teachers Room. Someone says, "What if a child gets injured? We’ll be liable."

Sylvie defends the tree. “In all the years no one has ever gotten hurt. Kids fall off the playground swings all the time. So why don’t you outlaw the swings?”

“Oh, Sylvie,” someone else says. “Come on.”

“Isn't part of being a kid swinging and falling off?”

Apparently not if it leaves the teachers vulnerable to legal action.

Lorna, who teaches the top sixth grade: “Anyway, it’s too close to the brick wall. A kid could end up smashing his head like an apple.”

“So tie a tire to the end of it. It’ll make a great swing.”

"What is this, someone's backyard?" Marla Frost snaps.

She directs her comment to the light fixture above them, to demonstrate that she is not talking to Sylvie.

They have been on the outs since Marla accused Sylvie of assigning an inappropriate book to one of her 6th graders because the cover showed a woman with big breasts. She made a federal case out of it, even calling the boy's parents, though Sylvie explained the book itself was fine, vocabulary and cognition level high, and she was just using the cover as a lure for the pre-teen. And it had worked. He passed. That’s what bothers Marla the most, Sylvie thinks.

Sylvie has always been the loyal opposition in the Teachers Room, the resident free spirit. She used to feel she was there to remind her fellow teachers to love the children as they correct them, and to lighten up when the job got serious. But, lately, her heart isn’t in it. Abruptly tired of the argument, she finishes her coffee, tosses the rest of her bagel and leaves.

|

Check out Bette's Popular Blog:

|

Bette Ann Moskowitz is an award-winning author and teacher born in Bronx, N.Y. She wrote her first book – a mystery - in a school notebook at the age of nine. A “true daughter” of the City University of New York (bachelor’s from Hunter College and master’s from Queens College), Bette has an eclectic resume, including writing publicity for Decca Records, songs that garnered modest royalties, plays (one of which was granted an audition for Broadway), stand-up comic routines, op-eds and essays for The New York Times.

Her popular blog, Vinegar Mother, is posted every Monday. It is gaining readers by the tens. Readers say it is a good way to start out their week with a smile. The Sanctuary Team encourages readers to take a look! Bette has written several books, both fiction and non-fiction. Her memoir Do I Know You? A Family’s Journey through Aging and Alzheimer’s won a New York State Foundation for the Arts Fellowship for Literary Non-fiction and The Room at the End of the Hall: An Ombudsman’s Notebook was a Finalist in the same category. Her latest non-fiction book, Finishing Up, a personal look at the very public subject of aging and ageism in America, was published by DIO Press in 2020. She entered the digital publishing world with SANCTUARY and has continued with publication (and podcast) of her short story, “Hippopotamus” at Sunlitfiction.com. Bette was a 2017 Featured Artist in Sanctuary. |