Play & Book Excerpts

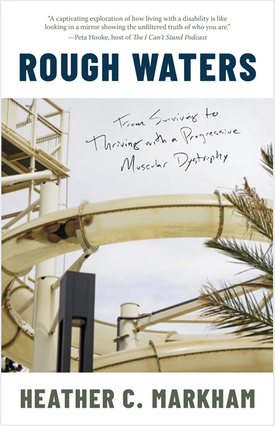

Rough Waters:

From Surviving to Thriving with a Progressive Muscular Dystrophy

(Making Waves for Good Publishing)

© Heather C. Markham

Excerpt is reprinted with permission from the author.

I sat on a table in one of the clinic’s exam rooms dressed in shorts, a T-shirt, and sneakers; I had set my cane and purse on a nearby chair. A neurology intern came in and performed manual muscle tests, just like my regular neurologist had done, and wrote down his findings. He left, and then the supervising UCLA neurologist came into the room. Tall and thin with mostly gray-white hair in a buzz cut, he had a severe look about him. He read the biopsy results with frowning concentration, then performed the same series of manual muscle tests—making notes about each muscle group—and compared his results to the intern’s.

We talked about my background, and that I’d been symptomatic since the injury in 1990 when I worked at Disney World.

He said, “So, it’s been a slow progression.”

I sharply replied, “Not to me it hasn’t.” To me, “slow” would have meant since birth. While I had been dealing with it for twelve years, in my mind time was compressed. All I remembered was pain.

He ignored that comment and, being satisfied that we were done, walked out.

Fifteen minutes later, a young woman appeared in the doorway and entered the room, carrying a clipboard. Her skirted suit and stiletto heels were in stark contrast to the sea of hospital scrubs that I’d seen. She introduced herself as a social worker and clinical liaison with the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA).

“So, you have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy,” she said, believing I’d already been informed, as she started to hand me pamphlets with the MDA logo on them.

“Oh, so that’s what it’s called?” I was just curious at this point. I had no idea what those words actually meant and couldn’t begin to register the shock.

She looked up from her clipboard, startled. “I’m not supposed to be the one to tell you!” Then she nearly ran from the room.

I quietly called after her. “Come back . . . it’s OK. I’m just glad to know its name.” I wasn’t angry at her. I was just relieved that, after all this time, it was finally called something.

A few minutes later, the senior neurologist came back in. “You have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [LGMD],” he said bluntly. “It’s kind of a garbage-can term for all muscular dystrophies that aren’t yet classified, like Duchenne or ALS are. There’s no medication for it; there’s no cure, and it generally isn’t fatal. It’s been slow progressing up to this point, and it will continue to be slow progressing. Do you have any questions?”

He delivered this overwhelming news like Walter Cronkite describing the latest national economic developments. For him, it was all facts. As a senior physician, whose focus was on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), he saw people like me at the MDA clinic daily, so this was just another routine day for him. But not for me. I needed a bedside manner that was more reassuring. One that said I had a future worth living for.

Remaining calm, I said, “I thought it might be in the muscular dystrophy family, based on what I could find on the internet about trabecular fibers and trabecular myopathy.”

He practically rolled his eyes as he replied. “The information on the internet isn’t always right. Where did you find it?”

“The National Institutes of Health website. There doesn’t seem to be very much research on it, and I can’t access the only paper written about it in 1999 because it’s in the PubMed repository and I don’t have a subscription. Can you help me get it?”

He was surprised that I’d done enough research to want something retrieved from PubMed, and he agreed to get me a copy. I told him that I didn’t have any other questions. I mean, he’d just told me I had a disease they couldn’t slow down, cure, or even accurately define. What on earth was there to ask? No matter what I came up with, his answers would be educated guesses at best. I felt time slow down as my awareness dissolved into a fog and I began to go through the motions of someone who was still paying attention. He left the room, again, and the social worker came back with her clipboard and all sorts of handouts and pamphlets about the MDA, LGMD, and where to find support.

I focused on the traffic as I drove the hour and a half home.

Once I was back in the safety of my own space, I let myself read what she’d given me. The pamphlets had a lot of facts. LGMD is a group of rare progressive genetic disorders characterized by atrophy and weakness of the voluntary muscles of the hip and shoulder areas, and the weakness may spread to other areas. I learned that reaching overhead or holding my arms outstretched to do things like brushing my hair would become “increasingly hard to do.” And, as LGMD is slow moving, the average patient is generally symptomatic for twenty years before needing a wheelchair.

The relief of having a name for what I’d been enduring was short lived. Presumably these facts were supposed to offer hope, but I found them crushing. I’d already been having symptoms for twelve years. I was thirty-four years old and seeing my future ripped away from me in slow motion. I gave myself permission to be overwhelmed and cried for two days.

I stopped crying because, honestly, I was boring myself. I reasoned that, if I was boring myself, no one else would want to be around me either. I needed to get my act together.

The next week I called my parents and close friends, and I met with all of my EW bosses. I explained what LGMD was: genetic, slow, progressive, and debilitating. It wasn’t polymyositis, so it wasn’t going to kill me, and it wouldn’t interfere with my ability to think. My parents were glad it was named but sad at the prognosis. Friends I’d had in graduate school in Texas wanted me to come back there so I could be nearby and they could take care of me. My close friends at Edwards Air Force Base, including Teresa and Gary, were determined not to let this isolate me. My bosses agreed that they’d hired me for my brains and not my legs.

By October 2002, I had an official diagnosis. And I’d also been granted Top Secret clearance.

I sat on a table in one of the clinic’s exam rooms dressed in shorts, a T-shirt, and sneakers; I had set my cane and purse on a nearby chair. A neurology intern came in and performed manual muscle tests, just like my regular neurologist had done, and wrote down his findings. He left, and then the supervising UCLA neurologist came into the room. Tall and thin with mostly gray-white hair in a buzz cut, he had a severe look about him. He read the biopsy results with frowning concentration, then performed the same series of manual muscle tests—making notes about each muscle group—and compared his results to the intern’s.

We talked about my background, and that I’d been symptomatic since the injury in 1990 when I worked at Disney World.

He said, “So, it’s been a slow progression.”

I sharply replied, “Not to me it hasn’t.” To me, “slow” would have meant since birth. While I had been dealing with it for twelve years, in my mind time was compressed. All I remembered was pain.

He ignored that comment and, being satisfied that we were done, walked out.

Fifteen minutes later, a young woman appeared in the doorway and entered the room, carrying a clipboard. Her skirted suit and stiletto heels were in stark contrast to the sea of hospital scrubs that I’d seen. She introduced herself as a social worker and clinical liaison with the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA).

“So, you have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy,” she said, believing I’d already been informed, as she started to hand me pamphlets with the MDA logo on them.

“Oh, so that’s what it’s called?” I was just curious at this point. I had no idea what those words actually meant and couldn’t begin to register the shock.

She looked up from her clipboard, startled. “I’m not supposed to be the one to tell you!” Then she nearly ran from the room.

I quietly called after her. “Come back . . . it’s OK. I’m just glad to know its name.” I wasn’t angry at her. I was just relieved that, after all this time, it was finally called something.

A few minutes later, the senior neurologist came back in. “You have limb-girdle muscular dystrophy [LGMD],” he said bluntly. “It’s kind of a garbage-can term for all muscular dystrophies that aren’t yet classified, like Duchenne or ALS are. There’s no medication for it; there’s no cure, and it generally isn’t fatal. It’s been slow progressing up to this point, and it will continue to be slow progressing. Do you have any questions?”

He delivered this overwhelming news like Walter Cronkite describing the latest national economic developments. For him, it was all facts. As a senior physician, whose focus was on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), he saw people like me at the MDA clinic daily, so this was just another routine day for him. But not for me. I needed a bedside manner that was more reassuring. One that said I had a future worth living for.

Remaining calm, I said, “I thought it might be in the muscular dystrophy family, based on what I could find on the internet about trabecular fibers and trabecular myopathy.”

He practically rolled his eyes as he replied. “The information on the internet isn’t always right. Where did you find it?”

“The National Institutes of Health website. There doesn’t seem to be very much research on it, and I can’t access the only paper written about it in 1999 because it’s in the PubMed repository and I don’t have a subscription. Can you help me get it?”

He was surprised that I’d done enough research to want something retrieved from PubMed, and he agreed to get me a copy. I told him that I didn’t have any other questions. I mean, he’d just told me I had a disease they couldn’t slow down, cure, or even accurately define. What on earth was there to ask? No matter what I came up with, his answers would be educated guesses at best. I felt time slow down as my awareness dissolved into a fog and I began to go through the motions of someone who was still paying attention. He left the room, again, and the social worker came back with her clipboard and all sorts of handouts and pamphlets about the MDA, LGMD, and where to find support.

I focused on the traffic as I drove the hour and a half home.

Once I was back in the safety of my own space, I let myself read what she’d given me. The pamphlets had a lot of facts. LGMD is a group of rare progressive genetic disorders characterized by atrophy and weakness of the voluntary muscles of the hip and shoulder areas, and the weakness may spread to other areas. I learned that reaching overhead or holding my arms outstretched to do things like brushing my hair would become “increasingly hard to do.” And, as LGMD is slow moving, the average patient is generally symptomatic for twenty years before needing a wheelchair.

The relief of having a name for what I’d been enduring was short lived. Presumably these facts were supposed to offer hope, but I found them crushing. I’d already been having symptoms for twelve years. I was thirty-four years old and seeing my future ripped away from me in slow motion. I gave myself permission to be overwhelmed and cried for two days.

I stopped crying because, honestly, I was boring myself. I reasoned that, if I was boring myself, no one else would want to be around me either. I needed to get my act together.

The next week I called my parents and close friends, and I met with all of my EW bosses. I explained what LGMD was: genetic, slow, progressive, and debilitating. It wasn’t polymyositis, so it wasn’t going to kill me, and it wouldn’t interfere with my ability to think. My parents were glad it was named but sad at the prognosis. Friends I’d had in graduate school in Texas wanted me to come back there so I could be nearby and they could take care of me. My close friends at Edwards Air Force Base, including Teresa and Gary, were determined not to let this isolate me. My bosses agreed that they’d hired me for my brains and not my legs.

By October 2002, I had an official diagnosis. And I’d also been granted Top Secret clearance.

|

Heather C. Markham is an engineer, assistive technology professional, public speaker, competitive Para Surfer, educator, ADA architectural barriers specialist, golfer, and award-winning international photographer.

Her memoir, Rough Waters: From Surviving to Thriving with a Progressive Muscular Dystrophy was published in July 2023. Heather’s company, Making Waves for Good, launched in 2018 as an umbrella for a variety of ventures, including publishing and photographic projects and to help companies solve disability access problems they didn’t know they had—not just staying within ADA code but looking beyond it to make the world more accessible and usable for all. She currently lives in Phoenix, Arizona, with her super snuggly Maine coon cat. |

Heather C. Markham

Photo Credit: Madalyn Wydrzynski |

|