Play & Book Excerpts

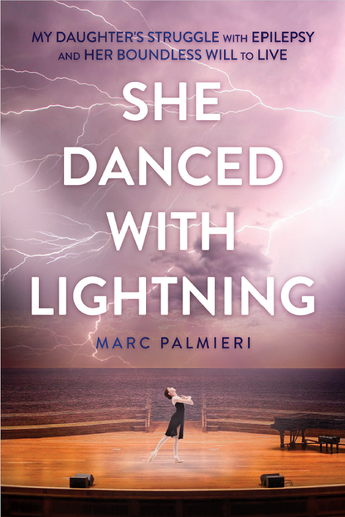

She Danced with Lightning

(Post Hill Press)

© Marc Palmieri

From Chapter 7 of SHE DANCED WITH LIGHTNING:

As Anna’s condition steadily worsens at 11-years-old, in the wake of another misdiagnosis suggesting that Anna is suffering not from seizures but a “panic disorder,” Marc is taking Anna to her first visit with a psychotherapist.

The office was classic. It was what I was used to with my therapist experiences: minimalist, neat, easy on the senses. It had a small sofa, on which Anna made herself immediately comfortable, and two armchairs where the doctor and I sat. The Ph D diploma and however many other degrees and certifications hung amid a few pieces of understated impressionist art. The day was bright outside but in here, all was gently lit by a shaded lamp beside the sofa. When we first spoke on the phone, I gave her an extensive description of all recent developments and, of course, Anna’s history. I’d expected to sign some forms, give a co-pay and wait outside in my car while Anna began this new frontier of self-examination, but I was asked to sit in.

On one hand, as always, I hoped Anna would get through this 45 minutes without any physical disruption. On the other, if an event had to happen, I thought it might not be a bad thing for it to happen in front of a psychologist, tasked with identifying a cause and coming up with a prevention.

As I sat in the armchair, the sight before me, was my 11-year-old laid out across the small room from a shrink. There it was, I thought: A live portrait of parenting failure. But before I could dwell too long in self-recrimination, Anna breezily launched into a sustained bitching session about school, some frenemies in her grade, her sister, and her parents.

“My parents are very mean and very strict,” she said. “Cruel people.”

“How are they cruel, Anna?” the doctor asked. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

“Well, they’re like, ‘Anna do this!’ and “Anna do that!’ And I’m, like, tired and, like, ugh.”

“Well, are these things they want you to do important?” the doctor continued.

“Yes,” I said, respectfully. “I think they are.”

“No!” Anna said.

“You mean like finish your homework, brush your teeth, make your bed… that stuff?” I continued. The doctor glanced at me, evaluating. I tried not to wonder what she was thinking.

“Yes!” Anna said. “Or, ‘Put your phone away’ or ‘Get in the shower!’”

“Yeah, those things are sort of necessary, Anna,” I said.

“I know, but all in a row?”

“What does that mean?” I said.

“Like, chill. Give me some time, bro. Like, one thing at a time?”

This had gotten ridiculous, fast. A few days ago I was in my father’s car holding her as she was having what I thought was a heart attack. We were told she had an acute anxiety disorder, and to treat it with psychotherapy to unearth the source of her stress. And this was it? Making her bed?

“Don’t you think your parents have to teach you those things?” the doctor asked.

“And they never hold hands,” Anna said.

That silenced the room for a good ten seconds. Now I was about to get my co-pay’s worth.

“Who doesn’t hold hands?” the doctor said.

“My parents.”

Another silence.

“You’re parents don’t…”

“They don’t love each other.”

“Anna…” I began.

“They don’t hold hands, or kiss, or hug…” Her eyes watered.

“Mommy and Daddy love each other,” I said. “And we love our girls very much.”

“And they don’t sleep in the same room because of me.”

“Anna,” I began, but said nothing else.

“They’ll get a divorce,” she said.

“Nobody’s getting a divorce,” I said. I turned to look at the therapist. I couldn’t really guarantee that, about a divorce, and she knew it.

“You’re always yelling and fighting.”

“We won’t get a divorce.”

I wondered if the doctor was finding this the simplest case she’d ever come across: Kid made a nervous wreck by two Type A, highly stressed, overworked, befuddled and scared out of their wits parents. Poor kid, she must be thinking. No wonder she has panic attacks. This was it, I thought, just hearing Anna say these things. It’s a panic disorder, and we caused it.

Something of a crackpot theory about Shakespeare’s play had occurred to me some years after Anna’s epilepsy lanced into our lives. I thought I knew why Shakespeare ended his comic Love’s Labour’s Lost like a tragedy, with the lovers parting, rather than marrying, as the audience would have expected. Shakespeare’s young son, Hamnet, died around the time he was writing it. I imagined the great playwright at his London theatre office, at his desk, working on his new hilarious romcom, probably called Love’s Labour’s Won. Then a messenger arrives from Stratford, where his wife and children lived. He’s flattened at the news, of course. So what does he do? Now that his heart was broken? His marriage was already pretty bad with all the distance, and now this? How does he even think about putting a new comedy on the stage? He changes the ending, that’s what he does, and the title. Nearly five acts of romantic hilarity, before he brings news of death onto the stage, and everyone ends up alone. The comedy is “lost.”

Hamnet was the same age as Anna when he died. Love’s Labour’s Lost premiered a year later.

That was our marriage, maybe. Love, then labor, kid. Then, for the unlucky some like us, it gets lost. Kristen and I had met in the most romantic and comedic circumstances – a great Hollywood story to tell our friends - and we, for a bit, came to know how to be characters in that kind of plot. But once Anna’s seizures came, and with them an everyday sadness, that happy romcom was over. What the hell were Kristen and I, who only knew each other a few young, fun years, doing now? This wasn’t what we foresaw when we got married. We ended up in the wrong play, half hoping every day that the curtain would come down on it.

“Ah, Anna,” I said. “Your mom and I do hold hands.”

The truth was, Kristen and I did hold hands every now and then, but not like Anna meant. These were moments Anna would never see. How would she? They’d be rolling her away for an MRI, lifting her into an ambulance, pinning her down for the needles and wires and tubes, as we, her goddam parents, hands clutched watched her disappear, from however close the doctors would let us get.

Used with permission of the publisher (Post Hill Press).

As Anna’s condition steadily worsens at 11-years-old, in the wake of another misdiagnosis suggesting that Anna is suffering not from seizures but a “panic disorder,” Marc is taking Anna to her first visit with a psychotherapist.

The office was classic. It was what I was used to with my therapist experiences: minimalist, neat, easy on the senses. It had a small sofa, on which Anna made herself immediately comfortable, and two armchairs where the doctor and I sat. The Ph D diploma and however many other degrees and certifications hung amid a few pieces of understated impressionist art. The day was bright outside but in here, all was gently lit by a shaded lamp beside the sofa. When we first spoke on the phone, I gave her an extensive description of all recent developments and, of course, Anna’s history. I’d expected to sign some forms, give a co-pay and wait outside in my car while Anna began this new frontier of self-examination, but I was asked to sit in.

On one hand, as always, I hoped Anna would get through this 45 minutes without any physical disruption. On the other, if an event had to happen, I thought it might not be a bad thing for it to happen in front of a psychologist, tasked with identifying a cause and coming up with a prevention.

As I sat in the armchair, the sight before me, was my 11-year-old laid out across the small room from a shrink. There it was, I thought: A live portrait of parenting failure. But before I could dwell too long in self-recrimination, Anna breezily launched into a sustained bitching session about school, some frenemies in her grade, her sister, and her parents.

“My parents are very mean and very strict,” she said. “Cruel people.”

“How are they cruel, Anna?” the doctor asked. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

“Well, they’re like, ‘Anna do this!’ and “Anna do that!’ And I’m, like, tired and, like, ugh.”

“Well, are these things they want you to do important?” the doctor continued.

“Yes,” I said, respectfully. “I think they are.”

“No!” Anna said.

“You mean like finish your homework, brush your teeth, make your bed… that stuff?” I continued. The doctor glanced at me, evaluating. I tried not to wonder what she was thinking.

“Yes!” Anna said. “Or, ‘Put your phone away’ or ‘Get in the shower!’”

“Yeah, those things are sort of necessary, Anna,” I said.

“I know, but all in a row?”

“What does that mean?” I said.

“Like, chill. Give me some time, bro. Like, one thing at a time?”

This had gotten ridiculous, fast. A few days ago I was in my father’s car holding her as she was having what I thought was a heart attack. We were told she had an acute anxiety disorder, and to treat it with psychotherapy to unearth the source of her stress. And this was it? Making her bed?

“Don’t you think your parents have to teach you those things?” the doctor asked.

“And they never hold hands,” Anna said.

That silenced the room for a good ten seconds. Now I was about to get my co-pay’s worth.

“Who doesn’t hold hands?” the doctor said.

“My parents.”

Another silence.

“You’re parents don’t…”

“They don’t love each other.”

“Anna…” I began.

“They don’t hold hands, or kiss, or hug…” Her eyes watered.

“Mommy and Daddy love each other,” I said. “And we love our girls very much.”

“And they don’t sleep in the same room because of me.”

“Anna,” I began, but said nothing else.

“They’ll get a divorce,” she said.

“Nobody’s getting a divorce,” I said. I turned to look at the therapist. I couldn’t really guarantee that, about a divorce, and she knew it.

“You’re always yelling and fighting.”

“We won’t get a divorce.”

I wondered if the doctor was finding this the simplest case she’d ever come across: Kid made a nervous wreck by two Type A, highly stressed, overworked, befuddled and scared out of their wits parents. Poor kid, she must be thinking. No wonder she has panic attacks. This was it, I thought, just hearing Anna say these things. It’s a panic disorder, and we caused it.

Something of a crackpot theory about Shakespeare’s play had occurred to me some years after Anna’s epilepsy lanced into our lives. I thought I knew why Shakespeare ended his comic Love’s Labour’s Lost like a tragedy, with the lovers parting, rather than marrying, as the audience would have expected. Shakespeare’s young son, Hamnet, died around the time he was writing it. I imagined the great playwright at his London theatre office, at his desk, working on his new hilarious romcom, probably called Love’s Labour’s Won. Then a messenger arrives from Stratford, where his wife and children lived. He’s flattened at the news, of course. So what does he do? Now that his heart was broken? His marriage was already pretty bad with all the distance, and now this? How does he even think about putting a new comedy on the stage? He changes the ending, that’s what he does, and the title. Nearly five acts of romantic hilarity, before he brings news of death onto the stage, and everyone ends up alone. The comedy is “lost.”

Hamnet was the same age as Anna when he died. Love’s Labour’s Lost premiered a year later.

That was our marriage, maybe. Love, then labor, kid. Then, for the unlucky some like us, it gets lost. Kristen and I had met in the most romantic and comedic circumstances – a great Hollywood story to tell our friends - and we, for a bit, came to know how to be characters in that kind of plot. But once Anna’s seizures came, and with them an everyday sadness, that happy romcom was over. What the hell were Kristen and I, who only knew each other a few young, fun years, doing now? This wasn’t what we foresaw when we got married. We ended up in the wrong play, half hoping every day that the curtain would come down on it.

“Ah, Anna,” I said. “Your mom and I do hold hands.”

The truth was, Kristen and I did hold hands every now and then, but not like Anna meant. These were moments Anna would never see. How would she? They’d be rolling her away for an MRI, lifting her into an ambulance, pinning her down for the needles and wires and tubes, as we, her goddam parents, hands clutched watched her disappear, from however close the doctors would let us get.

Used with permission of the publisher (Post Hill Press).

|

Marc Palmieri’s memoir, She Danced with Lightning, about life with his daughter’s journey with epilepsy, was recently published by Post Hill Press. His plays have been produced across the country and internationally, are all published by Dramatists Play Service, and include The New York Times’ “Critic’s Pick” Levittown as well as The Groundling, Carl the Second, and Waiting for the Host. He has published prose in Fiction, The Global City Review and (Re) An Ideas Journal. Screenplays include Miramax Films’ Telling You.

Marc is an assistant professor in the School of Liberal Arts at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, NY, where he is the recipient of the 2023 Outstanding Research Award, as well as the 2022 Faculty Innovation Award. He has been a guest faculty member for The City College of New York’s MFA program in creative writing since 2010. He played baseball for Wake Forest University, drafted by The Toronto Blue Jays, and still gets to coach high schoolers. |

Photo Credit: John Painz

|