Play & Book Excerpts

|

|

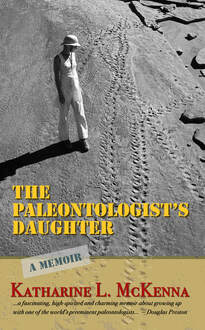

The Paleontologist's Daughter

(Ratski Publishing)

© 2020 Katharine L. McKenna

The Dead Cow

It has been a short summer. In my mind I relive this day—the sun kept flying across the sky from one mountain to another. We also fly across the mountains. I’m traveling with my family and Dad’s paleontological crew. We have a large group with us and we are going to camp at Willow Creek on our way to Utah. I haven’t been to Willow Creek in a long time; we’ve been using other camps as bases—Kelly and the Continental Divide, Hell’s Half Acre, Moccasin Basin and East Fork. I am excited to return to Willow Creek to the familiar place where I spent so much time when I was a little kid and where, my parents once confided, I was conceived.

After driving for a few miles along the old dirt road, I see the stand of cottonwood trees that surrounds the campsite. Their fluttering green leaves contrast with the dry sagebrush and dirt. We drive down into the groves and finally halt our caravan of trucks after a long day of driving. As the hum of the engines die, I absorb a sense of peace. I feel the presence of something sacred draped over the trees, like a canopy; the creek has changed its course some, but it still has that same quiet murmur while it polishes stones created eons ago. I take several deep breaths of the sagebrush-scented Wyoming air.

Although it has been a long while since I’ve visited Willow Creek, I know it well because of early childhood summers spent here. I see the creek and remember my desperation as I tried to recover my sneaker when it slipped from my fingers and floated fast and free down the creek. My older brother Doug and I improvised fishing poles out of sticks. Although we were amateurs at fishing, my father would give us red fish eggs that come in a jar to bait our hooks. After a short time, we would become bored and we’d set our rods against a tree, secure them with a rock and hope they might somehow snag a fish without our help.

I’m lucky to know that I was conceived in such a fine spot, which I grew to love by spending so much of my childhood here. Maybe I am part of this canyon and desert terrain, the way a trapeze artist born to the circus feels tied to that life and would never want to let go of it. My longing for this faded, simple life blows from one sagebrush to the next, like tumbleweed, always searching, never landing…

We unpack, and people start to set up cooking and sleeping quarters. We are going to stay for only one night. Familiar sounds soon overtake the silence. People are busy unpacking the trucks and yelling out to each other, “Where are the beans?” or “Hey, I think you’ve got my sleeping bag,” or “Doug, would you go see if you can find the Coleman stoves for me?” Then the booze comes out; field camp is never complete until a few Scotches have been poured before dinner. Someone is talking about the drive over the front range of the Rockies. Someone else is starting the fire, around which we will all sit and talk into the starlit night. These folks are veteran field campers. Scientists, geologists, paleontologists, grad students and us kids.

Then, without a prompt, something inspires me to remove myself from the familiar sounds. I want to be by myself and feel that sacred Wyoming silence again. I walk a few yards away from the camp. The cottonwood trees seem to retain their murmuring voices, as if they don’t want to let go of long-lost company. I walk further and stand still for a moment. I notice the sound of sheep bells and their baah-ing somewhere in the distance. I look in that direction, but I can’t see the sheep anywhere. They must be blending in with the sagebrush. I walk on.

I notice another cluster of cottonwood trees. They look just like our camp spot, but I don’t recognize them. I walk into this grove and instantly feel an odd weight of air descend upon me and, instinctively, I hold my breath. I can no longer hear the voices or the creek. I stand motionless and the heavy silence surrounds me, but it is not at all the quiet of our camp site. There is a smell that is near visible; a dankness that is weighting the air.

I walk on a little farther and come face to face with the corpse of a cow. I don’t just walk over to this dead cow and look at it, but rather, I feel that this cow and I and are meeting one another. I’m not afraid of its deadness and it doesn’t disgust me. I feel as though the dead cow actually knew I would come in there—it almost says to me, “Good evening, I’ve been waiting for you.” The sacred silence gives me the impression that no being but me has seen this cow since it died. The cow was once alive and living like me, and when it was alive, it could not have had the capacity to interpret me. But now that it is dead, I feel that it is the only thing or force that can comprehend me. It knows me. I feel at ease with it, almost attached to it. A once hard-working beast, now dead, but somehow all the wiser. I stare at it. Yes, you know all about me. You know about the stillness of everything. You’re dead, and you can laugh. But me, I’m living and I have to struggle still, against myself, against a thousand things.

The cow has been dead for some time, but it still reeks. I am able to get close to it on the upwind side without suffocating. I pick up a stick and touch it. The insides have all rotted away, but the hide is still intact, sunken between and around the ribs and eye sockets. After another moment, I see that flies are crawling all over it. Their buzzing breaks our silence. Although I could have stood there and stared at it longer, I feel a sudden urge to leave it behind.

I walk back toward the other group of trees, our trees, and I hear the happy muddled voices drift out and then blend in with the sound of forks, their tines scraping metal camp plates. The group sounds so secure inside that grove of trees. They aren’t thinking about the things that I am. They are eating supper. I hear someone ask where I had been. I don’t answer, but maybe they didn’t really ask in the first place. When I finish my dinner, the sun has disappeared and it is getting late. I snuggle up inside my old sleeping bag after the dishes are done and the fire has died out. I lie under the trees, the stars and moon, maybe on the very spot where I began, years ago. I wonder about the dead cow before I fall asleep to the murmur of the creek and the ringing of sheep bells still distant, but somehow, all the more audible.

After driving for a few miles along the old dirt road, I see the stand of cottonwood trees that surrounds the campsite. Their fluttering green leaves contrast with the dry sagebrush and dirt. We drive down into the groves and finally halt our caravan of trucks after a long day of driving. As the hum of the engines die, I absorb a sense of peace. I feel the presence of something sacred draped over the trees, like a canopy; the creek has changed its course some, but it still has that same quiet murmur while it polishes stones created eons ago. I take several deep breaths of the sagebrush-scented Wyoming air.

Although it has been a long while since I’ve visited Willow Creek, I know it well because of early childhood summers spent here. I see the creek and remember my desperation as I tried to recover my sneaker when it slipped from my fingers and floated fast and free down the creek. My older brother Doug and I improvised fishing poles out of sticks. Although we were amateurs at fishing, my father would give us red fish eggs that come in a jar to bait our hooks. After a short time, we would become bored and we’d set our rods against a tree, secure them with a rock and hope they might somehow snag a fish without our help.

I’m lucky to know that I was conceived in such a fine spot, which I grew to love by spending so much of my childhood here. Maybe I am part of this canyon and desert terrain, the way a trapeze artist born to the circus feels tied to that life and would never want to let go of it. My longing for this faded, simple life blows from one sagebrush to the next, like tumbleweed, always searching, never landing…

We unpack, and people start to set up cooking and sleeping quarters. We are going to stay for only one night. Familiar sounds soon overtake the silence. People are busy unpacking the trucks and yelling out to each other, “Where are the beans?” or “Hey, I think you’ve got my sleeping bag,” or “Doug, would you go see if you can find the Coleman stoves for me?” Then the booze comes out; field camp is never complete until a few Scotches have been poured before dinner. Someone is talking about the drive over the front range of the Rockies. Someone else is starting the fire, around which we will all sit and talk into the starlit night. These folks are veteran field campers. Scientists, geologists, paleontologists, grad students and us kids.

Then, without a prompt, something inspires me to remove myself from the familiar sounds. I want to be by myself and feel that sacred Wyoming silence again. I walk a few yards away from the camp. The cottonwood trees seem to retain their murmuring voices, as if they don’t want to let go of long-lost company. I walk further and stand still for a moment. I notice the sound of sheep bells and their baah-ing somewhere in the distance. I look in that direction, but I can’t see the sheep anywhere. They must be blending in with the sagebrush. I walk on.

I notice another cluster of cottonwood trees. They look just like our camp spot, but I don’t recognize them. I walk into this grove and instantly feel an odd weight of air descend upon me and, instinctively, I hold my breath. I can no longer hear the voices or the creek. I stand motionless and the heavy silence surrounds me, but it is not at all the quiet of our camp site. There is a smell that is near visible; a dankness that is weighting the air.

I walk on a little farther and come face to face with the corpse of a cow. I don’t just walk over to this dead cow and look at it, but rather, I feel that this cow and I and are meeting one another. I’m not afraid of its deadness and it doesn’t disgust me. I feel as though the dead cow actually knew I would come in there—it almost says to me, “Good evening, I’ve been waiting for you.” The sacred silence gives me the impression that no being but me has seen this cow since it died. The cow was once alive and living like me, and when it was alive, it could not have had the capacity to interpret me. But now that it is dead, I feel that it is the only thing or force that can comprehend me. It knows me. I feel at ease with it, almost attached to it. A once hard-working beast, now dead, but somehow all the wiser. I stare at it. Yes, you know all about me. You know about the stillness of everything. You’re dead, and you can laugh. But me, I’m living and I have to struggle still, against myself, against a thousand things.

The cow has been dead for some time, but it still reeks. I am able to get close to it on the upwind side without suffocating. I pick up a stick and touch it. The insides have all rotted away, but the hide is still intact, sunken between and around the ribs and eye sockets. After another moment, I see that flies are crawling all over it. Their buzzing breaks our silence. Although I could have stood there and stared at it longer, I feel a sudden urge to leave it behind.

I walk back toward the other group of trees, our trees, and I hear the happy muddled voices drift out and then blend in with the sound of forks, their tines scraping metal camp plates. The group sounds so secure inside that grove of trees. They aren’t thinking about the things that I am. They are eating supper. I hear someone ask where I had been. I don’t answer, but maybe they didn’t really ask in the first place. When I finish my dinner, the sun has disappeared and it is getting late. I snuggle up inside my old sleeping bag after the dishes are done and the fire has died out. I lie under the trees, the stars and moon, maybe on the very spot where I began, years ago. I wonder about the dead cow before I fall asleep to the murmur of the creek and the ringing of sheep bells still distant, but somehow, all the more audible.

|

Katharine L. McKenna was born in Berkeley, California and is a long-time resident of Woodstock, NY. She divides her time between the Hudson Valley and the American West.

Katharine received a B.A. in American Studies with a concentration in Anthropology from Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT and a Masters of Industrial Design from Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY. She has worked in a variety of disciplines over the years, including museum exhibition design, computer user interface design, and color consultation. She serves on the boards of Pratt Institute, the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild and the Lemur Conservation Foundation. Her memoir The Paleontologist's Daughter shares an intriguing story of her life as the daughter of a world-renowned paleontologist. Katharine is also an award-winning painter whose work is featured in galleries and private collections throughout the world. Find out more about the inspiration behind her artwork HERE. Dancing Grasses

Oil on Linen - 36 X 40 © Katharine L. McKenna (Click image above for more about Katharine's art.) |