Play & Book Excerpts

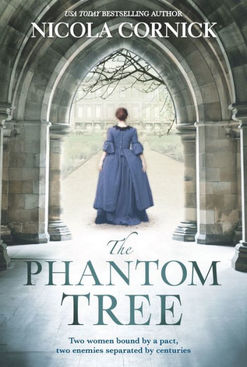

The Phantom Tree

(Graydon House)

© 2017 Nicola Cornick

She saw the portrait quite by chance, or so she thought.

It was eight weeks to Christmas and the rain sodden streets of Marlborough already glistened in the gaudy light of the decorations that were strung from buildings and lampposts. The wind was strong that night and the illuminations swung back and forth scattering shadows and shards of colour over the late-night shoppers below. A Victorian market was being held in the town square and the air was thick with the smell of grilled sausages and hot soup. It made Alison feel hungry. She put her head down and increased her pace against the fine rain that slicked the pavements. She hated this sort of faux historical event with rosy, smiling stallholders dressed up in costume. Beneath the crinolines and jackets they had on their thermal vests and long johns to guard against the cold.

They had waterproof boots and raincoats. They thought this play-acting was fun, a jolly celebration of Christmas past.

She remembered past Christmases very differently; the bone sharp cold, the damp, the chilblains and the hunger that had hollowed her stomach. Even though she had been trapped in the present day for so long now that time had started to blur, some of her past she could remember with utter clarity. Pain, sickness, violence, death, had been a raw reality. Someone thrust a toffee apple under her nose in an invitation to buy, and she shuddered and turned away, picking up her pace along the pavement.

There was a creaking noise high above her, a flap as the wind caught the edge of an inn sign and set it swinging.

The White Hart.

She stared at the image of the majestic white stag as it swayed backwards and forwards in the wind. Its head was raised proudly. Around its neck was a golden crown. It was strange how the most potent and magical of Savernake Forest’s symbols survived into this brash and modern world. There were traces of history everywhere; in street names, on inn signs, in old tracks and ancient hedgerows, buried walls and tumbled gravestones. Scratch the surface and it was there. Alison had seen a white hart in the forest once. Her cousin Edward Seymour had said that the Queen had wanted to come to hunt it, the hart being the ultimate hunter’s trophy and Elizabeth being a queen who collected such things. Perhaps she had come to Wolf Hall after Alison had left. She did not know. There was no record of a royal visit but then so much fell through the cracks of the past.

The fresh blast of air from the Downs to the north brought with it a softer scent, of mingled herbs and flowers, wild garlic, basil and lavender, taking Alison straight back to a long-lost summer in the garden at Wolf Hall and the smell of sun-warm brick and hot grass. She had not been happy in those days but still the sense of loss and dislocation hit her fiercely and gave her no time to prepare. There was too much that was familiar here in Marlborough—the town, the inn, the memories. She should have realised that coming back to Wiltshire was a bad idea. But she had had so little choice.

Breathe. Accept. Wait.

The wave of dizziness and nausea retreated a little. Alison found she was leaning against a wall between two shops, rather like a drunk steadying himself as he tried to weave his way home late at night. Awareness returned to her, the smooth coldness of a drainpipe against her clutching fingers, the chill sting of the rain and the heavy, greasy smell of the street market.

She was standing in front of a shop she had not seen before. High street shops came and went, of course, and it was a good ten years since she had been in Marlborough, maybe more. She tried not to count most of the time.

The shop was actually an art gallery, all high-tech lighting and huge windows, its modernity blaringly incongruous in the middle of Marlborough High Street’s olde-worlde charm. Most of the paintings Alison could see through the window were equally strident, highly coloured, swirling patterns in oil with huge price tags and no artistic merit in her opinion. Not that she knew much about art. She drew for pleasure and had done since she was a child, but she had no training and no technique to speak of.

To the right of the enormous bow window was a pastoral scene with a spotlight trained on it. It might have been an antique. Alison could not really tell. Below the canvas ran a broad white shelf that stretched along the full length of the showroom. There were a number of smaller paintings displayed there, mainly portraits, and she knew at once that they were old, sixteenth century, to judge from the style and the type of clothing. There was King Henry VIII, painted at the moment his glorious, golden youthfulness was changing into something more watchful and inimical. When Alison had been a child, his name had been used to frighten them all into obedience: ‘Behave yourself or old King Hal will come to get you.’ When she had been young she had had no idea what he had looked like but her imagination had supplied the image of a monster. She had seen hundreds of pictures of him since, of course. The English were proud of their infamous, spouse-murdering monarch. Distance had lent the sort of affection to his memory that had never been felt in her own time.

It was odd seeing Henry now, a relic, a throwback to her past. It unsettled her.

Alison’s gaze travelled on to the next portrait on the shelf, that of a woman, standing, her hands folded demurely in that style so beloved of artists who wanted to persuade the viewer that Tudor womanhood was modest and decorous. The dis- play light cast a shadow across her face. Alison strained closer to see. This was no one as instantly recognisable as Henry and yet there was a familiarity about her. It was a face she knew.

Mary Seymour.

It was eight weeks to Christmas and the rain sodden streets of Marlborough already glistened in the gaudy light of the decorations that were strung from buildings and lampposts. The wind was strong that night and the illuminations swung back and forth scattering shadows and shards of colour over the late-night shoppers below. A Victorian market was being held in the town square and the air was thick with the smell of grilled sausages and hot soup. It made Alison feel hungry. She put her head down and increased her pace against the fine rain that slicked the pavements. She hated this sort of faux historical event with rosy, smiling stallholders dressed up in costume. Beneath the crinolines and jackets they had on their thermal vests and long johns to guard against the cold.

They had waterproof boots and raincoats. They thought this play-acting was fun, a jolly celebration of Christmas past.

She remembered past Christmases very differently; the bone sharp cold, the damp, the chilblains and the hunger that had hollowed her stomach. Even though she had been trapped in the present day for so long now that time had started to blur, some of her past she could remember with utter clarity. Pain, sickness, violence, death, had been a raw reality. Someone thrust a toffee apple under her nose in an invitation to buy, and she shuddered and turned away, picking up her pace along the pavement.

There was a creaking noise high above her, a flap as the wind caught the edge of an inn sign and set it swinging.

The White Hart.

She stared at the image of the majestic white stag as it swayed backwards and forwards in the wind. Its head was raised proudly. Around its neck was a golden crown. It was strange how the most potent and magical of Savernake Forest’s symbols survived into this brash and modern world. There were traces of history everywhere; in street names, on inn signs, in old tracks and ancient hedgerows, buried walls and tumbled gravestones. Scratch the surface and it was there. Alison had seen a white hart in the forest once. Her cousin Edward Seymour had said that the Queen had wanted to come to hunt it, the hart being the ultimate hunter’s trophy and Elizabeth being a queen who collected such things. Perhaps she had come to Wolf Hall after Alison had left. She did not know. There was no record of a royal visit but then so much fell through the cracks of the past.

The fresh blast of air from the Downs to the north brought with it a softer scent, of mingled herbs and flowers, wild garlic, basil and lavender, taking Alison straight back to a long-lost summer in the garden at Wolf Hall and the smell of sun-warm brick and hot grass. She had not been happy in those days but still the sense of loss and dislocation hit her fiercely and gave her no time to prepare. There was too much that was familiar here in Marlborough—the town, the inn, the memories. She should have realised that coming back to Wiltshire was a bad idea. But she had had so little choice.

Breathe. Accept. Wait.

The wave of dizziness and nausea retreated a little. Alison found she was leaning against a wall between two shops, rather like a drunk steadying himself as he tried to weave his way home late at night. Awareness returned to her, the smooth coldness of a drainpipe against her clutching fingers, the chill sting of the rain and the heavy, greasy smell of the street market.

She was standing in front of a shop she had not seen before. High street shops came and went, of course, and it was a good ten years since she had been in Marlborough, maybe more. She tried not to count most of the time.

The shop was actually an art gallery, all high-tech lighting and huge windows, its modernity blaringly incongruous in the middle of Marlborough High Street’s olde-worlde charm. Most of the paintings Alison could see through the window were equally strident, highly coloured, swirling patterns in oil with huge price tags and no artistic merit in her opinion. Not that she knew much about art. She drew for pleasure and had done since she was a child, but she had no training and no technique to speak of.

To the right of the enormous bow window was a pastoral scene with a spotlight trained on it. It might have been an antique. Alison could not really tell. Below the canvas ran a broad white shelf that stretched along the full length of the showroom. There were a number of smaller paintings displayed there, mainly portraits, and she knew at once that they were old, sixteenth century, to judge from the style and the type of clothing. There was King Henry VIII, painted at the moment his glorious, golden youthfulness was changing into something more watchful and inimical. When Alison had been a child, his name had been used to frighten them all into obedience: ‘Behave yourself or old King Hal will come to get you.’ When she had been young she had had no idea what he had looked like but her imagination had supplied the image of a monster. She had seen hundreds of pictures of him since, of course. The English were proud of their infamous, spouse-murdering monarch. Distance had lent the sort of affection to his memory that had never been felt in her own time.

It was odd seeing Henry now, a relic, a throwback to her past. It unsettled her.

Alison’s gaze travelled on to the next portrait on the shelf, that of a woman, standing, her hands folded demurely in that style so beloved of artists who wanted to persuade the viewer that Tudor womanhood was modest and decorous. The dis- play light cast a shadow across her face. Alison strained closer to see. This was no one as instantly recognisable as Henry and yet there was a familiarity about her. It was a face she knew.

Mary Seymour.

|

Photo Credit: Andrew Cornick

|

Nicola Cornick is a writer and historian who was born and brought up in the north of England. Nicola developed a passion for history at an early age and nurtured it through reading and watching BBC costume dramas with her grandmother.

She went on to study medieval history and graduated with honors from London University. She worked for many years in academia until she gave it all up to be a full time author. Later she returned to college in Oxford to pursue a master’s degree in history. Since the publication of her first Regency romance by Harlequin Mills & Boon in 1998, Nicola has become an award-winning author. She now writes dual timeframe novels inspired by the history and legends of her local area. Nicola also works as a guide and historian for the National Trust at the beautiful seventeenth century hunting lodge, Ashdown House. She gives talks on various aspects of her historical research and is a former Wiltshire Libraries Writer in Residence and trustee of the Wantage Literary Festival. Nicola is the current chair of the Romantic Novelists’ Association and a member of the Society of Authors. |