Play & Book Excerpts

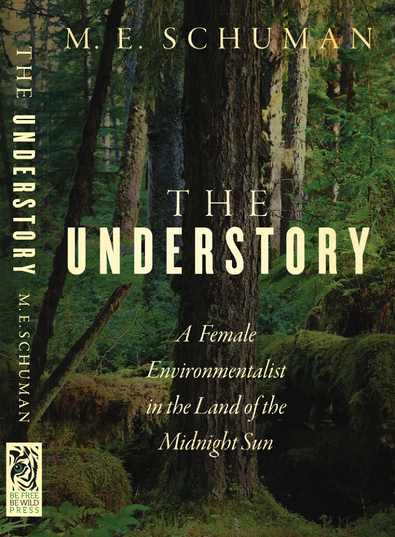

The Understory

A Female Environmentalist in the Land of the Midnight Sun

© Be Free Be Wild Press

Reflections of a Wilderness Wanderer

I was born in a small, rural town in eastern Washington, where I was free to explore the basalt cliffs and sagebrush fields. After receiving my undergraduate degree in wildlife biology, range management, and soil science, I married my soul mate, whom I met working in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. Our adventure took us to California, where my husband was a mechanical engineer, and Nevada, where I tracked wild horses. And then, I was offered a position in Alaska, working with reindeer and muskox. We thought it destiny, as his company also had a position in Alaska. Early on in our Alaskan dream, the love of my life, was tragically killed, propelling me on a tumultuous journey of a male-dominated culture that routinely diminished and disrespected the accomplishments and abilities of women. I experienced with great dismay the ways in which greed and ambition so easily place humanity and the environment in jeopardy. My memoir, The Understory, is the culmination of my desire to control my own destiny, through the healing lessons of nature and my love of writing. I'm currently living in Florida, pursuing writing and wandering, looking for a community to call home.

I was born in a small, rural town in eastern Washington, where I was free to explore the basalt cliffs and sagebrush fields. After receiving my undergraduate degree in wildlife biology, range management, and soil science, I married my soul mate, whom I met working in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. Our adventure took us to California, where my husband was a mechanical engineer, and Nevada, where I tracked wild horses. And then, I was offered a position in Alaska, working with reindeer and muskox. We thought it destiny, as his company also had a position in Alaska. Early on in our Alaskan dream, the love of my life, was tragically killed, propelling me on a tumultuous journey of a male-dominated culture that routinely diminished and disrespected the accomplishments and abilities of women. I experienced with great dismay the ways in which greed and ambition so easily place humanity and the environment in jeopardy. My memoir, The Understory, is the culmination of my desire to control my own destiny, through the healing lessons of nature and my love of writing. I'm currently living in Florida, pursuing writing and wandering, looking for a community to call home.

Excerpt from Chapter 21 – Black Death

Greed, I whispered, as tears flowed down my smudged cheeks. The rage and disgust curdled my stomach. For months, I breathed the pungent benzene. My tastebuds lost the ability to discern anything except the bitter, acrid taste of oil. Every pore of my skin exuded the contaminate.

My ‘coasty’ comrade and I watched the river otters in silence. After weeks on the Green Islands, which we nicknamed “Quail,” after our then vice president, all we saw was black crude, in the water and on the rocky shoreline. One otter ran back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, on the rocky shore — frantic, as her mate shadowed her in the water. He could not find an opening to her through the thick, slimy, black poison to reach his mate.

What did I know about oil spills? Absolutely nothing.

Juneau, the capital, is a quaint and quiet town between the end of the legislative session and before the summer tourists arrive. There are no roads to the capital. Access is only by ferry or plane. And the best part was the Gastineau Channel is the gateway to sailing and boating among the hundreds of islands.

As my supervisor suspected, despite my lack of confidence, I learned quickly about oil spill containment and the laws that regulate the business of producing and transporting hazardous materials. While attending a week of oil spill training in Texas, the reality of a large-scale disaster in Alaskan waters hit me full force. It was not if, but when. The inadequacy of enforcement, because of the political influence Big Oil has in the state, was blatant.

Shortly after midnight on March 24, 1989, the 987-foot oil tanker Exxon Valdez, piloted by the ship's third mate, ran aground on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska, spilling nearly 11 million gallons of tar-like crude oil and creating America's biggest environmental disaster.

Two days later, I joined Justin on an Alaska Airlines flight from Juneau to Anchorage. Flying over Prince William Sound, the pilot circled, diverging from the normal flight path. Below, we saw the shimmering rainbow of colors spreading from the tanker, 27,000 feet below us. The pristine, calm and productive waters of Prince William Sound, with not a boat or yellow boom in sight for miles, were unprotected from the assault.

Once on the ground in Anchorage, Justin took me to the National Guard compound where I found my next flight, to Valdez, as I walked up the rear ramp of a C-130 loaded with skimming equipment. After take-off, I visited with the pilots in the cockpit until they gave me the word to strap in tight. The big ox of a plane was already bucking. I did as I was told as I watched the wings bouncing up and down, rolling the C-130 from side to side. A wind warning was in place for Valdez.

As I walked out the ramp, I saw planes flipped, cables swinging. I murmured to myself; mother nature is one angry lady today.

Dan was holding meetings in a makeshift incident command center in the Valdez Courthouse. He knew I had expertise in soil, plants, and wildlife. He assigned me to the Beach Assessment team to document the damage.

The priority was identification of the “seal pupping areas” and deploying booms. This was the critical time for mother seals to give birth to pups in the upper limits of the beach. But you couldn’t deploy a boom if you did not have it!

Then someone yelled, “hey you!” I turned toward him as he rushed up to me, and he handed me a plastic bag of jars. He told me to get to the harbor. A shrimper was coming in loaded. Say what? I thought, as I looked at the gentleman and then at the baggy. He noted my confusion; I did not know even where the harbor was. He quietly explained what I needed to do and the importance of the task. I found out later he was Alaska Attorney General Douglas Baily.

I boarded the shrimp boat and nearly broke down when I saw the nets and the shrimp. The shrimp, called spots, is one of the largest species in the world and found in the deeper waters of Prince William Sound. Their body is normally a reddish brown with white horizontal bars on the carapace. They have distinctive white spots on their abdomen. I saw nothing but blackened bodies. Everything the shrimper had, his net, his boat, his livelihood, coated with black slime. The smell made me nauseous.

Shaking, I recorded the information and took samples, carefully placing them in the containers, apologizing for what happened.

That night, I dragged my duffel and my sleeping bag to the courtroom to catch some sleep. While the oil spread along Alaska's pristine coastline, citizens both there and farther south waited. The first three days of the spill had not a breath of wind and the seas were unusually calm. Days went by while corporate and government officials bickered. Meanwhile, the spill, 25 miles from Valdez, polluted over 1,000 miles of beaches, killed over 36,000 migratory birds and thousands of sea mammals and bald eagles were dead.

Greed, I whispered, as tears flowed down my smudged cheeks. The rage and disgust curdled my stomach. For months, I breathed the pungent benzene. My tastebuds lost the ability to discern anything except the bitter, acrid taste of oil. Every pore of my skin exuded the contaminate.

My ‘coasty’ comrade and I watched the river otters in silence. After weeks on the Green Islands, which we nicknamed “Quail,” after our then vice president, all we saw was black crude, in the water and on the rocky shoreline. One otter ran back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, on the rocky shore — frantic, as her mate shadowed her in the water. He could not find an opening to her through the thick, slimy, black poison to reach his mate.

What did I know about oil spills? Absolutely nothing.

Juneau, the capital, is a quaint and quiet town between the end of the legislative session and before the summer tourists arrive. There are no roads to the capital. Access is only by ferry or plane. And the best part was the Gastineau Channel is the gateway to sailing and boating among the hundreds of islands.

As my supervisor suspected, despite my lack of confidence, I learned quickly about oil spill containment and the laws that regulate the business of producing and transporting hazardous materials. While attending a week of oil spill training in Texas, the reality of a large-scale disaster in Alaskan waters hit me full force. It was not if, but when. The inadequacy of enforcement, because of the political influence Big Oil has in the state, was blatant.

Shortly after midnight on March 24, 1989, the 987-foot oil tanker Exxon Valdez, piloted by the ship's third mate, ran aground on Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound, Alaska, spilling nearly 11 million gallons of tar-like crude oil and creating America's biggest environmental disaster.

Two days later, I joined Justin on an Alaska Airlines flight from Juneau to Anchorage. Flying over Prince William Sound, the pilot circled, diverging from the normal flight path. Below, we saw the shimmering rainbow of colors spreading from the tanker, 27,000 feet below us. The pristine, calm and productive waters of Prince William Sound, with not a boat or yellow boom in sight for miles, were unprotected from the assault.

Once on the ground in Anchorage, Justin took me to the National Guard compound where I found my next flight, to Valdez, as I walked up the rear ramp of a C-130 loaded with skimming equipment. After take-off, I visited with the pilots in the cockpit until they gave me the word to strap in tight. The big ox of a plane was already bucking. I did as I was told as I watched the wings bouncing up and down, rolling the C-130 from side to side. A wind warning was in place for Valdez.

As I walked out the ramp, I saw planes flipped, cables swinging. I murmured to myself; mother nature is one angry lady today.

Dan was holding meetings in a makeshift incident command center in the Valdez Courthouse. He knew I had expertise in soil, plants, and wildlife. He assigned me to the Beach Assessment team to document the damage.

The priority was identification of the “seal pupping areas” and deploying booms. This was the critical time for mother seals to give birth to pups in the upper limits of the beach. But you couldn’t deploy a boom if you did not have it!

Then someone yelled, “hey you!” I turned toward him as he rushed up to me, and he handed me a plastic bag of jars. He told me to get to the harbor. A shrimper was coming in loaded. Say what? I thought, as I looked at the gentleman and then at the baggy. He noted my confusion; I did not know even where the harbor was. He quietly explained what I needed to do and the importance of the task. I found out later he was Alaska Attorney General Douglas Baily.

I boarded the shrimp boat and nearly broke down when I saw the nets and the shrimp. The shrimp, called spots, is one of the largest species in the world and found in the deeper waters of Prince William Sound. Their body is normally a reddish brown with white horizontal bars on the carapace. They have distinctive white spots on their abdomen. I saw nothing but blackened bodies. Everything the shrimper had, his net, his boat, his livelihood, coated with black slime. The smell made me nauseous.

Shaking, I recorded the information and took samples, carefully placing them in the containers, apologizing for what happened.

That night, I dragged my duffel and my sleeping bag to the courtroom to catch some sleep. While the oil spread along Alaska's pristine coastline, citizens both there and farther south waited. The first three days of the spill had not a breath of wind and the seas were unusually calm. Days went by while corporate and government officials bickered. Meanwhile, the spill, 25 miles from Valdez, polluted over 1,000 miles of beaches, killed over 36,000 migratory birds and thousands of sea mammals and bald eagles were dead.

|

Michelle Schuman

|

Michelle Schuman is an environmental scientist with over four decades of experience in Alaska. She has worked in the private sector, developing environmental impact statements and conducting field surveys from the northern tundra to the rainforest of southeast Alaska. As an Oil Spill Ecologist for the State of Alaska, her most notable and arduous accomplishment was acting as a first responder on the Exxon Oil Spill, analyzing one of the most devastating and long-term man-caused disasters in North American history. She recently retired as the Ecologist for the USDA after twenty years, where she is well known for her expertise in wetland science and environmental policy.

In October 2020, she began writing her memoir, The Understory: A Female Environmentalist in the Land of the Midnight Sun. A year later, she signed an option agreement with HTWIP Productions for a screenplay. Michelle is most comfortable among the colors of nature, exploring ecosystems around the globe. For now, she is content to write, tell her story, and give a voice to the underserved and undervalued, who live in the understory, waiting to bloom and burst with energy. She holds a B.S. degree in wildlife biology and a master’s in environmental policy. Michelle is a Certified Senior Ecologist and Professional Certified Wetland Scientist. As an advocate for climate change awareness, animal welfare and gender equality, Michelle’s passion is to pursue fictional story writing while weaving the issues that affect our environment and natural world. UPCOMING AUTHOR EVENT:

Meet & Greet / Author Signing August 3 ~ 6:00 p.m. Books Inc. Palo Alto, CA At this event, Lauren Weston, Executive Director of Acterra, will interview Michelle in a discussion about the environment and her memoir. This is a 'Scientist to Scientist' conversation! |