Play & Book Excerpts

|

|

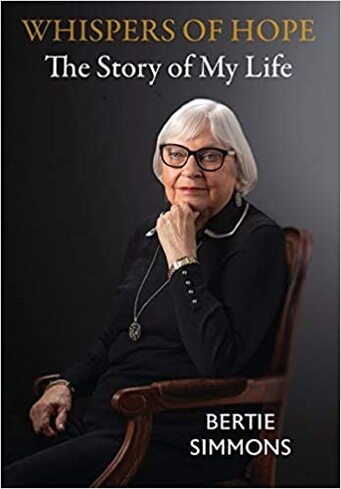

Whispers of Hope: The Story of My Life

(Independently Published)

© 2019 Bertie Simmons

From CHAPTER 40: The Rumble

The unbelievable was happening! Despite all the hard work, we clearly had not adequately dealt with the gang problem on campus. That did not prevent a school riot that erupted in the fall of 2002 when street gangs from outside the campus came on campus to attack several of the Furr gangsters. Metal garbage cans were sailing through the air and hitting students on the head. Students were fighting each other and outsiders that I did not recognize. The courtyard resembled a war zone filled with screaming, fighting individuals throwing gang signs and beating each other to a pulp in a sea of trash. Police officers were assisting in gaining and maintaining order, as ambulances were carrying injured individuals away. I was aghast!

When the outsiders had escaped, I learned that the assistant principals had decided to send thirty-two of our students, gang members all, to an alternative school. This was the action always taken in such cases but was never effective. I decided to take a risk and insisted upon a different approach. I wanted to determine if we might take actions that would result in an end to the violence on campus and perhaps change the behavior of the gang members permanently. The district’s established guidelines required that the students be removed from the campus and placed in an alternative setting. The question was whether such action changed student behavior. We all agreed that it did not.

The school had been complying with district rules and had been removing students who engaged in gang violence. It was still impossible to hold assemblies or student activities on campus without fear of gang fights. Having allowed the school culture to be dictated by a fear of gang activity for years, we clearly saw that some other action had to be taken to create a safe environment. I did not know exactly what I was going to do or if it would work. I knew all the culprits by name and the personal history of each one. I had a feeling that I could reach them and change their behavior. It seemed worth a try.

I decided to call all the identified students in and have a discussion with them. I told them the action that we had decided to take in response to their involvement in the riot. They were obviously surprised and thanked me for not sending them to an alternative school. That response opened the door for me to inform them that they had to take responsibility for their inappropriate actions, and each would be required to sign a behavior contract. Although they were reluctant to answer me for a while, I probed them with questions. Finally, they began to talk, and their remarks were remarkably revealing about their beliefs and lifestyles.

The students informed me that they trusted no one outside their families and other gang members. They said, “We really don’t trust public officials because they don’t give a damn about us. The government is against us because we’re minority and poor. They think we’re dumb.” I was shocked and amazed when they explained that they believed 9/11 never happened and the government was using a movie to attempt to fool them.

After much discussion and honest discourse, I informed them that I knew for a fact that 9/11 did happen and how our entire nation was changed because of the disaster. I emphasized that they were mistaken about the events of 9/11. When I asked what actions could be taken to bring peace into their lives and peace to the Furr campus, they fell quiet. Eventually they all agreed that if they could see Ground Zero with their own eyes, then they would have more faith in others and especially in the government. Without hesitation, I agreed to take all thirty-two of them to New York City if there were no more gang fights at Furr during the 2002–2003 school year. I agreed to take the trip the following June. We drew up a contract, and the thirty-two of them signed it.

Once we had signed the contract, I had no doubt that I would be able to obtain the funds for the trip. After all, didn’t everyone want to contribute to a trip to New York City for a group of gang members? Right? Wrong! When I approached the individuals in the HISD Office of Strategic Management about the possibility of obtaining corporate donations to take thirty-two gang members to see Ground Zero, they were appalled. One replied in hushed tones, “I would keep that agreement you have with the students very quiet because people will think you are crazy!”

Since I clearly would get no support from the school district, I approached corporations on my own. None were willing to help. We tried fund raising, but in a community where no one has money, there was no chance of raising the funds.

It was now April, there had been no gang fights on campus, and I had no funds to take the trip. Suddenly, money began pouring in from all over and from as far away as Hawaii. Consultants I was using believed in what I was trying to do, and not only did they contribute but their families, friends, and celebrities contributed. Before I knew it, we had the funds and were eagerly making plans for the trip.

The gang members were terrified when they learned that we would be flying to New York City. They had never flown in an airplane and were certain the plane would crash.

“Couldn’t you please drive us, Miss,” they begged. “Please, Miss!”

“I am an old woman,” I told them. “I am not about to drive a group of thugs to New York!” The “gangsters” laughed heartily and continued to beg.

The teachers thought I was rewarding inappropriate student behavior. They remarked, “I can’t wait to see when they have a gang fight in New York City. It’s going to be all over the news.”

We decided to also take all nine members of the National Honor Society so we rewarded them as well. Can you imagine what it would be like to have thirty-two gangsters and nine National Honor Society members on the same trip to New York? Actually, it was wonderful!

While in the city, we visited the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, Central Park, and the United Nations. After our visit to the United Nations, one of the docents remarked that this was the most informed group of students that had ever visited there.

One of the experiences the students enjoyed most in New York City was when we took in a Broadway musical, 42nd Street. Before we went to the performance, the students asked if there would be mariachi music or hip-hop. When I told them there would be neither, they were unsure they wanted to attend. But once they were in the theater and the musical began, they were spellbound and begged me to take them back the next night.

Then there was the day when we finally visited Ground Zero. Afterwards, I entered St. Paul’s Chapel. I saw all our gang members on their knees at the altar of the church. Later they came to the back of the church, and one remarked to me, “Miss, I bet you didn’t know we prayed, did you?”

“Sure, I knew you prayed,” I said. “I’m sure you were praying for the people who lost their families and friends in the Twin Towers on 9/11.”

“No, Miss,” he replied. “We were praying that our plane won’t crash on the way back to Houston.”

The four days that we spent in New York City with Furr students was a life-changing experience for them and enlightening to all of us. We had no trouble with any of the students, and when we returned to Houston and held our debriefing session, one of the National Honor Society students, who was also a magnet student, remarked, “One important thing I learned is that gang members and magnet students are really no different. It’s just that we have had different experiences. Now, I consider some of the gang members my friends.”

When these gang members were students at Furr High School, there were no gang fights on campus. Most of them graduated, and I still hear from some of them even today. One sent me a picture of him in uniform and informed me he was on his way to Iraq. Even after these students graduated, it became rare to have a student fight on campus.

The unbelievable was happening! Despite all the hard work, we clearly had not adequately dealt with the gang problem on campus. That did not prevent a school riot that erupted in the fall of 2002 when street gangs from outside the campus came on campus to attack several of the Furr gangsters. Metal garbage cans were sailing through the air and hitting students on the head. Students were fighting each other and outsiders that I did not recognize. The courtyard resembled a war zone filled with screaming, fighting individuals throwing gang signs and beating each other to a pulp in a sea of trash. Police officers were assisting in gaining and maintaining order, as ambulances were carrying injured individuals away. I was aghast!

When the outsiders had escaped, I learned that the assistant principals had decided to send thirty-two of our students, gang members all, to an alternative school. This was the action always taken in such cases but was never effective. I decided to take a risk and insisted upon a different approach. I wanted to determine if we might take actions that would result in an end to the violence on campus and perhaps change the behavior of the gang members permanently. The district’s established guidelines required that the students be removed from the campus and placed in an alternative setting. The question was whether such action changed student behavior. We all agreed that it did not.

The school had been complying with district rules and had been removing students who engaged in gang violence. It was still impossible to hold assemblies or student activities on campus without fear of gang fights. Having allowed the school culture to be dictated by a fear of gang activity for years, we clearly saw that some other action had to be taken to create a safe environment. I did not know exactly what I was going to do or if it would work. I knew all the culprits by name and the personal history of each one. I had a feeling that I could reach them and change their behavior. It seemed worth a try.

I decided to call all the identified students in and have a discussion with them. I told them the action that we had decided to take in response to their involvement in the riot. They were obviously surprised and thanked me for not sending them to an alternative school. That response opened the door for me to inform them that they had to take responsibility for their inappropriate actions, and each would be required to sign a behavior contract. Although they were reluctant to answer me for a while, I probed them with questions. Finally, they began to talk, and their remarks were remarkably revealing about their beliefs and lifestyles.

The students informed me that they trusted no one outside their families and other gang members. They said, “We really don’t trust public officials because they don’t give a damn about us. The government is against us because we’re minority and poor. They think we’re dumb.” I was shocked and amazed when they explained that they believed 9/11 never happened and the government was using a movie to attempt to fool them.

After much discussion and honest discourse, I informed them that I knew for a fact that 9/11 did happen and how our entire nation was changed because of the disaster. I emphasized that they were mistaken about the events of 9/11. When I asked what actions could be taken to bring peace into their lives and peace to the Furr campus, they fell quiet. Eventually they all agreed that if they could see Ground Zero with their own eyes, then they would have more faith in others and especially in the government. Without hesitation, I agreed to take all thirty-two of them to New York City if there were no more gang fights at Furr during the 2002–2003 school year. I agreed to take the trip the following June. We drew up a contract, and the thirty-two of them signed it.

Once we had signed the contract, I had no doubt that I would be able to obtain the funds for the trip. After all, didn’t everyone want to contribute to a trip to New York City for a group of gang members? Right? Wrong! When I approached the individuals in the HISD Office of Strategic Management about the possibility of obtaining corporate donations to take thirty-two gang members to see Ground Zero, they were appalled. One replied in hushed tones, “I would keep that agreement you have with the students very quiet because people will think you are crazy!”

Since I clearly would get no support from the school district, I approached corporations on my own. None were willing to help. We tried fund raising, but in a community where no one has money, there was no chance of raising the funds.

It was now April, there had been no gang fights on campus, and I had no funds to take the trip. Suddenly, money began pouring in from all over and from as far away as Hawaii. Consultants I was using believed in what I was trying to do, and not only did they contribute but their families, friends, and celebrities contributed. Before I knew it, we had the funds and were eagerly making plans for the trip.

The gang members were terrified when they learned that we would be flying to New York City. They had never flown in an airplane and were certain the plane would crash.

“Couldn’t you please drive us, Miss,” they begged. “Please, Miss!”

“I am an old woman,” I told them. “I am not about to drive a group of thugs to New York!” The “gangsters” laughed heartily and continued to beg.

The teachers thought I was rewarding inappropriate student behavior. They remarked, “I can’t wait to see when they have a gang fight in New York City. It’s going to be all over the news.”

We decided to also take all nine members of the National Honor Society so we rewarded them as well. Can you imagine what it would be like to have thirty-two gangsters and nine National Honor Society members on the same trip to New York? Actually, it was wonderful!

While in the city, we visited the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, Central Park, and the United Nations. After our visit to the United Nations, one of the docents remarked that this was the most informed group of students that had ever visited there.

One of the experiences the students enjoyed most in New York City was when we took in a Broadway musical, 42nd Street. Before we went to the performance, the students asked if there would be mariachi music or hip-hop. When I told them there would be neither, they were unsure they wanted to attend. But once they were in the theater and the musical began, they were spellbound and begged me to take them back the next night.

Then there was the day when we finally visited Ground Zero. Afterwards, I entered St. Paul’s Chapel. I saw all our gang members on their knees at the altar of the church. Later they came to the back of the church, and one remarked to me, “Miss, I bet you didn’t know we prayed, did you?”

“Sure, I knew you prayed,” I said. “I’m sure you were praying for the people who lost their families and friends in the Twin Towers on 9/11.”

“No, Miss,” he replied. “We were praying that our plane won’t crash on the way back to Houston.”

The four days that we spent in New York City with Furr students was a life-changing experience for them and enlightening to all of us. We had no trouble with any of the students, and when we returned to Houston and held our debriefing session, one of the National Honor Society students, who was also a magnet student, remarked, “One important thing I learned is that gang members and magnet students are really no different. It’s just that we have had different experiences. Now, I consider some of the gang members my friends.”

When these gang members were students at Furr High School, there were no gang fights on campus. Most of them graduated, and I still hear from some of them even today. One sent me a picture of him in uniform and informed me he was on his way to Iraq. Even after these students graduated, it became rare to have a student fight on campus.

|

Follow Bertie on:

|

For 58 years, Bertie Simmons, Ed.D., author of Whispers of Hope: The Story of My Life, was a dedicated educator in the Houston Independent School District (HISD).

Bertie’s many positions for HISD include Assistant Superintendent, District Superintendent, Associate Superintendent, and Executive Director. After retiring in 1995, she returned to the district in 2000 to serve as the principal of Furr High School for 17 years. She is the recipient of countless honors, including Teacher of the Year, HEB’s Best High School Principal in Texas award (2011) and KHOU’s Schools Now Spirit of Texas award. As evidence of Bertie's indelible impact on Furr High School, education advocate and philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs (wife of the late Apple, Inc. CEO, Steve Jobs) recognized Furr High School in 2016 as a recipient of a $10 million grant through the XQ Super School Project. Bertie's school was one of 10 selected from nearly 700 schools nationwide for “reimagining high school education.” |