April 2024 Featured Artist

A Celebration of Heritage, Our Natural World, and the Good Things in Life

An Interview with

Kay WalkingStick

|

Kay WalkingStick

Photo Credit: Grace Roselli (Pandoras Box X Project) |

Kay WalkingStick is a proud member of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Of Cherokee/Anglo heritage, she is a painter of extraordinary power. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, the Museum of Canada in Ottawa, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, The Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Museum of the American Indian, DC, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, DC, and many others. Hales Gallery represents her work in New York City and Europe.

Among her numerous awards are the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award, the Lee Krasner Award for Lifetime Achievement, and the National Endowment of the Arts. Her vast landscapes are beautiful testaments to America, evoking the eternal beauty of nature. In her own words, they are meant “to glorify our land and honor those people who first lived upon it.” Kay and her husband, artist Dirk Bach, live and paint in a townhouse in Easton, Pennsylvania. Find information and links to Kay's current exhibitions at the end of this interview. |

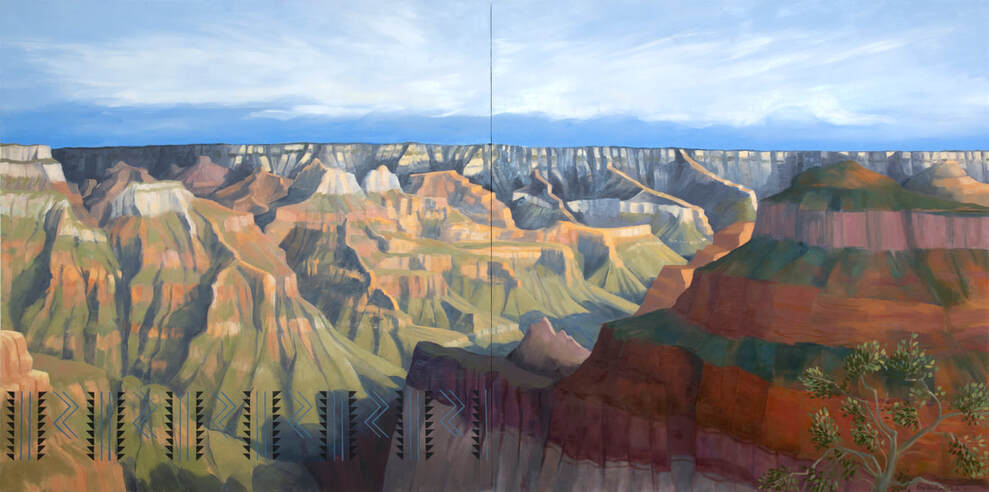

On the North Rim

Oil on Panel ~ 31.75 x 63.5 inches

© Kay WalkingStick

Oil on Panel ~ 31.75 x 63.5 inches

© Kay WalkingStick

Sandra Bertrand, travel & culture editor, recently had the honor and great pleasure of speaking with Kay about her work and found her to be warm, engaging, and passionately committed to her painting and the “great pleasures of life.”

At a young age, your mother told you stories of your father and your Cherokee heritage. Do you remember your first thoughts about that?

This is who we were. We were Indians in my world, and we had these Indian names and sometimes people laughed at that, but my mother always said, ‘Stand up straight and be proud. You are a Cherokee.’

You had siblings?

She had four other children when she left my father, pregnant with me. This was during the Depression and times were hard. My father became a severe alcoholic. He had a good education at Dartmouth. He had been in the first World War and largely in India, in the British YWCA of all things. He was an interesting and complex guy who worked in the oil fields — he was a geologist.

I just accepted I was an Indian. My siblings were all raised around my father, and other Native people. They were raised in Oklahoma. I was the only one who was not.

Were you close to your siblings when you were a child? Did you get to know them?

Oh, very close. My brother used to carry me around on his shoulders. I must’ve been maybe a year and a half old. I can remember hanging onto his hair. But my oldest brother, Sy, died in the Second World War when he was just 22, so I didn’t know him as well as the others. He died in Luzan, in the Philippines. And that was a hard time for everybody.

At a young age, your mother told you stories of your father and your Cherokee heritage. Do you remember your first thoughts about that?

This is who we were. We were Indians in my world, and we had these Indian names and sometimes people laughed at that, but my mother always said, ‘Stand up straight and be proud. You are a Cherokee.’

You had siblings?

She had four other children when she left my father, pregnant with me. This was during the Depression and times were hard. My father became a severe alcoholic. He had a good education at Dartmouth. He had been in the first World War and largely in India, in the British YWCA of all things. He was an interesting and complex guy who worked in the oil fields — he was a geologist.

I just accepted I was an Indian. My siblings were all raised around my father, and other Native people. They were raised in Oklahoma. I was the only one who was not.

Were you close to your siblings when you were a child? Did you get to know them?

Oh, very close. My brother used to carry me around on his shoulders. I must’ve been maybe a year and a half old. I can remember hanging onto his hair. But my oldest brother, Sy, died in the Second World War when he was just 22, so I didn’t know him as well as the others. He died in Luzan, in the Philippines. And that was a hard time for everybody.

Do you remember when you first began drawing?

I always tell people I learned to draw in church. I had a religious childhood, and we would go to church and sit in the balcony during long services — they were always an hour and a half, so my mother would give me paper and pencil and say, 'Draw!'

What would you draw?

I would draw little things I thought about. I liked to draw ice skaters. I was enamored of Sonia Henie. I even had a Sonia Henie doll. There was a giant rose window in the church. It was gorgeous…for a kid to be looking at this in the morning with the sun shining through, it was just a glorious experience.

And it also says something about how things affected you visually at a very early age.

Very early. My mother’s family were all artists. So, the reason she expected me to draw was because they all could. It’s in the gene package.

My father would draw me cartoons. In kindergarten we were allowed to draw little stick figures but when I put a nose on one of them, I was told that the class wasn’t doing that yet.

I had a teacher who told me when I was making colorful things and filling in the lines, ‘We’re only using yellow and blue today.’

We weren’t supposed to be sophisticated at five to do it any other way!

I’ve drawn all my life. It’s always been a part of how I saw myself. I didn’t realize I wanted to be a painter until I went to college, and I’ve been doing that ever since.

In that vein, when you began to take your art seriously, do you remember struggles? Not in terms of your heritage but as a woman?

Well, you know I went to college in the 1950s, and women were expected to get married right out of college and be lovely wives, intelligent and witty wives! And so not a lot was expected of us. My mother, on the other hand, had a very different approach. She said to me, ‘Kay, make something of yourself.’ Very firmly, like that. There were no jokes there. ‘A smart little girl like you should make something of herself.’

I love that.

And she said ‘You know, Kay, maybe you’ll have a man who will support you all your life, but you can’t depend on that. You must have a way to take care of yourself.’ It wasn’t like I was 21 when I heard that, I was probably eight. And I’m convinced that I am who I am because my mother told me to shape up. She had confidence in me that I could do what I wanted to do, although I’m not sure she believed I could make a living as an artist.

I always tell people I learned to draw in church. I had a religious childhood, and we would go to church and sit in the balcony during long services — they were always an hour and a half, so my mother would give me paper and pencil and say, 'Draw!'

What would you draw?

I would draw little things I thought about. I liked to draw ice skaters. I was enamored of Sonia Henie. I even had a Sonia Henie doll. There was a giant rose window in the church. It was gorgeous…for a kid to be looking at this in the morning with the sun shining through, it was just a glorious experience.

And it also says something about how things affected you visually at a very early age.

Very early. My mother’s family were all artists. So, the reason she expected me to draw was because they all could. It’s in the gene package.

My father would draw me cartoons. In kindergarten we were allowed to draw little stick figures but when I put a nose on one of them, I was told that the class wasn’t doing that yet.

I had a teacher who told me when I was making colorful things and filling in the lines, ‘We’re only using yellow and blue today.’

We weren’t supposed to be sophisticated at five to do it any other way!

I’ve drawn all my life. It’s always been a part of how I saw myself. I didn’t realize I wanted to be a painter until I went to college, and I’ve been doing that ever since.

In that vein, when you began to take your art seriously, do you remember struggles? Not in terms of your heritage but as a woman?

Well, you know I went to college in the 1950s, and women were expected to get married right out of college and be lovely wives, intelligent and witty wives! And so not a lot was expected of us. My mother, on the other hand, had a very different approach. She said to me, ‘Kay, make something of yourself.’ Very firmly, like that. There were no jokes there. ‘A smart little girl like you should make something of herself.’

I love that.

And she said ‘You know, Kay, maybe you’ll have a man who will support you all your life, but you can’t depend on that. You must have a way to take care of yourself.’ It wasn’t like I was 21 when I heard that, I was probably eight. And I’m convinced that I am who I am because my mother told me to shape up. She had confidence in me that I could do what I wanted to do, although I’m not sure she believed I could make a living as an artist.

But she had an unshakable belief in you.

An unshakable belief that I could go out and do things. There were nine years between myself and my older sister, the next one in line. I also had another sister. I was the only baby at home, and she didn’t have the trauma of dealing with my father as she did around the other kids, so I think she spent more time with me.

I had three younger sisters, and I was eight years old before my second sister arrived, so my mother made a fuss over everything I did.

Oh, absolutely. First and last children are different from other kids in the family. There are benefits to being part of a big family as well, but nevertheless, I believe that my mother’s insistence that I was going to do something special soaked in, which at that time was kind of a revolutionary idea. Girls were expected to be servile. Even the professional roles were more servile than running the company!

Exactly.

It’s hard for young women today to understand how different it was. Because it wasn’t a small number of people who thought this way, it was the mores of the culture.

An unshakable belief that I could go out and do things. There were nine years between myself and my older sister, the next one in line. I also had another sister. I was the only baby at home, and she didn’t have the trauma of dealing with my father as she did around the other kids, so I think she spent more time with me.

I had three younger sisters, and I was eight years old before my second sister arrived, so my mother made a fuss over everything I did.

Oh, absolutely. First and last children are different from other kids in the family. There are benefits to being part of a big family as well, but nevertheless, I believe that my mother’s insistence that I was going to do something special soaked in, which at that time was kind of a revolutionary idea. Girls were expected to be servile. Even the professional roles were more servile than running the company!

Exactly.

It’s hard for young women today to understand how different it was. Because it wasn’t a small number of people who thought this way, it was the mores of the culture.

Seal Rock Storm

Oil on Panel ~ 40 x 80 inches

© Kay WalkingStick

Oil on Panel ~ 40 x 80 inches

© Kay WalkingStick

Another thing I want to get into is your relationship with nature, your landscapes — the land, the oceans, the skies, the importance of that in your work. You’ve said when you’re painting those landscapes, you want to know how they smell, how they look, to give them the “slow gaze.” When you were traveling through the Southwest, did you have plans to go back or do you have plans to seek out a new landscape?

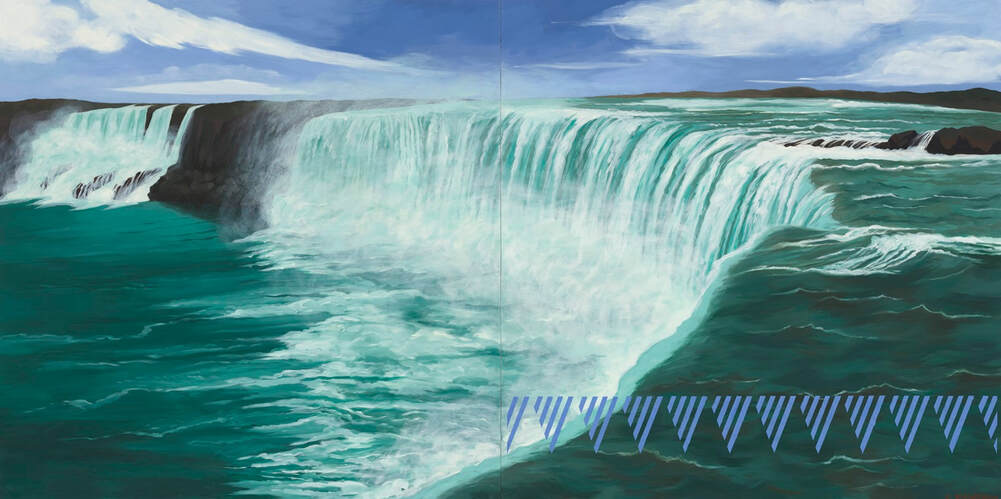

Let’s see, it was the 1980s (1985 or 1986) when I spent a semester in Durango, Colorado teaching at Fort Lewis College. I had a wonderful experience there because the mountains were a continuous backdrop, and I was doing abstraction at the time. One of the reasons I started doing landscapes was the effect of living for a short time in Durango. So, I think I’m going to try and go back there and take another look. Of course, it’s near the Four Corners, near Mesa Verde, if you know that. Near Arizona and New Mexico. But the next painting I’m going to do — I work on wood panels, you know — is another one of Niagara. I happen to like the one I did for the New York Historical Society (NYHS) a lot.

It’s a standout in the show.

The distance between those falls to the New York Rainbow Falls is greater than what I did — I have conflated that space a bit. So, I want to stretch it out over three panels instead of two, and it may work or not.

I’m sure it will.

One never knows.

Let’s see, it was the 1980s (1985 or 1986) when I spent a semester in Durango, Colorado teaching at Fort Lewis College. I had a wonderful experience there because the mountains were a continuous backdrop, and I was doing abstraction at the time. One of the reasons I started doing landscapes was the effect of living for a short time in Durango. So, I think I’m going to try and go back there and take another look. Of course, it’s near the Four Corners, near Mesa Verde, if you know that. Near Arizona and New Mexico. But the next painting I’m going to do — I work on wood panels, you know — is another one of Niagara. I happen to like the one I did for the New York Historical Society (NYHS) a lot.

It’s a standout in the show.

The distance between those falls to the New York Rainbow Falls is greater than what I did — I have conflated that space a bit. So, I want to stretch it out over three panels instead of two, and it may work or not.

I’m sure it will.

One never knows.

Niagara

Oil on Panel ~ 101.6 x 101.6 inches (measurement for each panel)

© Kay WalkingStick

Photo Credit: JSP Art Photography

Oil on Panel ~ 101.6 x 101.6 inches (measurement for each panel)

© Kay WalkingStick

Photo Credit: JSP Art Photography

I have another question about the Indian patterns in your paintings. In the recent landscapes at the NYHS, you incorporated patterns of the Indian tribes endemic to that area. There’s the Haudenosaunee pattern.

Yes, the Haudenosaunee. The reason I didn’t use the people who lived right next door to the Falls and the people who lived on the other side (Canadian Falls) is because their patterns are very circular, very beautiful — they’re decorative like bead work, floral and curvilinear, and I can’t cut those stencils. I can do a slight curve, but there’s a lot of curves and impossible to cut. Somebody else can but I can’t. So, I used a Mohawk pattern because people of that area moved around enough and were close enough to one another so that you could look at a Mohawk pattern and mistake it for an Onondaga pattern. And that pattern, used from a Mohawk jar, is also seen in the Seneca further west toward the Falls. It was a fairly generalized pattern of New York State.

Do you see yourself continuing to incorporate patterns of a specific geographical area like you did in those big paintings?

I’ve been doing that for probably ten years, and I don’t see any point in stopping. I really want people to hear the message. The way to get people to hear it is to repeat it. As I said, I was raised in church and the sermons always had a central idea presented at least three times. That’s the way you teach.

The importance of repetition.

Yes. So, the patterns aren’t exactly the same, but the point is always to stop people. It’s a kind of barrier, to stop a person’s eye. You look at it and say, ‘What the heck is that doing there?’ And I want people to stop and see that there’s an Indian pattern there and not something else. And they’re different in each area because the patterns of each tribe are different. A person who knows about tribal painting, crafts, baskets or rugs will know it’s a specific tribe. There’s a book about parfleche bags* by Gaylord Torrance. A wonderful book that I depended upon. When you look at the book you can see the difference in the patterns — there’s tremendous difference.

*Description of parfleche bags. (Britannica.com)

An amazing art form.

The thing is that patterns are only similar if they are neighbors. For instance, the tribes that are the more northerly tribes, the Nez Perce, the Nakota in Canada, there is a similarity there. With the Crow, there’s a similarity because they’re neighbors. When you go south, they’re still making parfleche bags, but they’re very different. Very linear.

Someone once asked if I could speak Indian. And of course, I laughed at her, but maybe she didn’t realize how stupid that was because there are well over 350 Indian languages in the United States, and they’re as different as Chinese is from English. There are all these differences between us. It’s something that people don’t generally understand.

I think most people don’t have any idea how diverse those cultures are. We didn't learn a lot in school. What we learned was mostly from watching old cowboy and Indian films. If you wear a certain kind of headdress, you’re an Indian, but that’s as far as the knowledge would go.

I’m hoping that the educators today are doing it a little differently. But I don’t know that for sure.

You’ve also embraced the idea that we should hold on to a particular culture but recognize our shared being.

Yes. An important concept.

The importance of harmony among human beings has never been more essential, so I think some of your work — maybe your mission or inspiration — comes from the realization of how important it is to get along.

Yes, and I think the patterns are saying to people wherever you live in the Western Hemisphere, you are living on Indian land — this is Indian territory — and I think that is an important thing for people to recognize. These people should be allowed to be on their land that we’re all on. A lot of this land has been stolen through treaties. And it’s also true we must find a way to get along with one another through non-combative and non-destructive ways.

And one of the things that inspired me in the sixties was that first walk on the moon, the excitement of hearing those astronauts when they returned to earth talking about how we were all together on this little blue ball, that we all had the same home.

Yes, we all have the same home. And that’s another thing that I think my paintings are about —they’re about this beautiful planet. I paint this beautiful earth, and it’s beautiful everywhere you go, unless it’s over industrialized. This is the planet that’s perfect for us. The only planet. Part of seeing my landscapes is to look at this earth, this is what we have. This beautiful place. We have to take care of it.

It’s almost a sacred mission, isn’t it?

Yes. So, if I have a message at all, it’s that we’re here. We have to take care of this.

Do you have any words of advice for today’s young woman? What would be the first thing you would think of in terms of her advancement, her survival in setting out on a career in the arts?

Hang on. Just hang on. The thing is, don’t give up. Real success is still making art, [even if] you’re an old, old lady (mutual laughter). It isn’t the money. It isn’t the shows or the accolades. It’s getting into the studio and making art. That’s success.

Yes, and that really is what’s going to save all of us — finding a way to just do something that matters to you.

Working at what you love.

And that brings me to my last question. Where do you find your sanctuary?

My sanctuary? Well, I’ve always loved to travel, but that’s adventure, not sanctuary. I would have to say, simply, home. I cook. I guess someone else would call it a hobby, but I like to cook, and I find it very relaxing. I have two children. My daughter lives in Philadelphia, and I see her a couple of times a month at the very least. My son lives in New Jersey. I don’t see him as often but speak to him on the phone quite a bit. So, I find my simple pleasures.

There was a Greek philosopher, a couple of millennia ago, who spoke of tending one’s own garden — I think it was Zeno — and that’s basically what I do. I enjoy my family.

It sounds like you’re doing all the things that are simply about being alive.

And enjoying life, the great pleasures of life. Every philosopher says it’s these simple things — every philosopher I should say that I respect. (Laughter) These are the great gifts, having a happy home and happy children.

I love to travel. But there’s the wonderful experience of coming home, of putting what’s important in life into perspective.

Yes, and I’ve always been a big reader, but I think that comes with all of this. Reading is part of this enjoyment of home life.

Well, I suppose you could take your book to the park.

(Laughter). Yes. And I enjoy going into the studio. It keeps me sane.

Yes.

It always has because it’s thinking about something that has meaning, something that’s outside your own mishigas (craziness) and whatever’s going on in your head. Painting takes you to another place, at least for me, so it’s a physical activity and a mental activity, but it’s also a soul activity.

A total immersion into that other world.

If you talk about sanctuary, you’d have to talk about that as a major part of the whole. I’ve always enjoyed travel and reading, etcetera, but working in the studio, having a full home life…I’ve had a good life. I’m very fortunate.

Yes, the Haudenosaunee. The reason I didn’t use the people who lived right next door to the Falls and the people who lived on the other side (Canadian Falls) is because their patterns are very circular, very beautiful — they’re decorative like bead work, floral and curvilinear, and I can’t cut those stencils. I can do a slight curve, but there’s a lot of curves and impossible to cut. Somebody else can but I can’t. So, I used a Mohawk pattern because people of that area moved around enough and were close enough to one another so that you could look at a Mohawk pattern and mistake it for an Onondaga pattern. And that pattern, used from a Mohawk jar, is also seen in the Seneca further west toward the Falls. It was a fairly generalized pattern of New York State.

Do you see yourself continuing to incorporate patterns of a specific geographical area like you did in those big paintings?

I’ve been doing that for probably ten years, and I don’t see any point in stopping. I really want people to hear the message. The way to get people to hear it is to repeat it. As I said, I was raised in church and the sermons always had a central idea presented at least three times. That’s the way you teach.

The importance of repetition.

Yes. So, the patterns aren’t exactly the same, but the point is always to stop people. It’s a kind of barrier, to stop a person’s eye. You look at it and say, ‘What the heck is that doing there?’ And I want people to stop and see that there’s an Indian pattern there and not something else. And they’re different in each area because the patterns of each tribe are different. A person who knows about tribal painting, crafts, baskets or rugs will know it’s a specific tribe. There’s a book about parfleche bags* by Gaylord Torrance. A wonderful book that I depended upon. When you look at the book you can see the difference in the patterns — there’s tremendous difference.

*Description of parfleche bags. (Britannica.com)

An amazing art form.

The thing is that patterns are only similar if they are neighbors. For instance, the tribes that are the more northerly tribes, the Nez Perce, the Nakota in Canada, there is a similarity there. With the Crow, there’s a similarity because they’re neighbors. When you go south, they’re still making parfleche bags, but they’re very different. Very linear.

Someone once asked if I could speak Indian. And of course, I laughed at her, but maybe she didn’t realize how stupid that was because there are well over 350 Indian languages in the United States, and they’re as different as Chinese is from English. There are all these differences between us. It’s something that people don’t generally understand.

I think most people don’t have any idea how diverse those cultures are. We didn't learn a lot in school. What we learned was mostly from watching old cowboy and Indian films. If you wear a certain kind of headdress, you’re an Indian, but that’s as far as the knowledge would go.

I’m hoping that the educators today are doing it a little differently. But I don’t know that for sure.

You’ve also embraced the idea that we should hold on to a particular culture but recognize our shared being.

Yes. An important concept.

The importance of harmony among human beings has never been more essential, so I think some of your work — maybe your mission or inspiration — comes from the realization of how important it is to get along.

Yes, and I think the patterns are saying to people wherever you live in the Western Hemisphere, you are living on Indian land — this is Indian territory — and I think that is an important thing for people to recognize. These people should be allowed to be on their land that we’re all on. A lot of this land has been stolen through treaties. And it’s also true we must find a way to get along with one another through non-combative and non-destructive ways.

And one of the things that inspired me in the sixties was that first walk on the moon, the excitement of hearing those astronauts when they returned to earth talking about how we were all together on this little blue ball, that we all had the same home.

Yes, we all have the same home. And that’s another thing that I think my paintings are about —they’re about this beautiful planet. I paint this beautiful earth, and it’s beautiful everywhere you go, unless it’s over industrialized. This is the planet that’s perfect for us. The only planet. Part of seeing my landscapes is to look at this earth, this is what we have. This beautiful place. We have to take care of it.

It’s almost a sacred mission, isn’t it?

Yes. So, if I have a message at all, it’s that we’re here. We have to take care of this.

Do you have any words of advice for today’s young woman? What would be the first thing you would think of in terms of her advancement, her survival in setting out on a career in the arts?

Hang on. Just hang on. The thing is, don’t give up. Real success is still making art, [even if] you’re an old, old lady (mutual laughter). It isn’t the money. It isn’t the shows or the accolades. It’s getting into the studio and making art. That’s success.

Yes, and that really is what’s going to save all of us — finding a way to just do something that matters to you.

Working at what you love.

And that brings me to my last question. Where do you find your sanctuary?

My sanctuary? Well, I’ve always loved to travel, but that’s adventure, not sanctuary. I would have to say, simply, home. I cook. I guess someone else would call it a hobby, but I like to cook, and I find it very relaxing. I have two children. My daughter lives in Philadelphia, and I see her a couple of times a month at the very least. My son lives in New Jersey. I don’t see him as often but speak to him on the phone quite a bit. So, I find my simple pleasures.

There was a Greek philosopher, a couple of millennia ago, who spoke of tending one’s own garden — I think it was Zeno — and that’s basically what I do. I enjoy my family.

It sounds like you’re doing all the things that are simply about being alive.

And enjoying life, the great pleasures of life. Every philosopher says it’s these simple things — every philosopher I should say that I respect. (Laughter) These are the great gifts, having a happy home and happy children.

I love to travel. But there’s the wonderful experience of coming home, of putting what’s important in life into perspective.

Yes, and I’ve always been a big reader, but I think that comes with all of this. Reading is part of this enjoyment of home life.

Well, I suppose you could take your book to the park.

(Laughter). Yes. And I enjoy going into the studio. It keeps me sane.

Yes.

It always has because it’s thinking about something that has meaning, something that’s outside your own mishigas (craziness) and whatever’s going on in your head. Painting takes you to another place, at least for me, so it’s a physical activity and a mental activity, but it’s also a soul activity.

A total immersion into that other world.

If you talk about sanctuary, you’d have to talk about that as a major part of the whole. I’ve always enjoyed travel and reading, etcetera, but working in the studio, having a full home life…I’ve had a good life. I’m very fortunate.

Current Exhibitions:

Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School

New-York Historical Society

170 Central Park West

at Richard Gilder Way (77th Street)

New York, NY

Now through April 14, 2024

This artistic dialogue showcases the ways in which Kay’s work both connects to and diverges from the

Hudson River School tradition and explores the agency of art in shaping humankind’s relationship to the land.

Deconstructing the Tipi

Hales Gallery

547 West 20th Street

New York, NY

Now through April 27, 2024

This solo exhibit centers around Kay's early abstractions from the mid-1970s,

engaging with her indigenous heritage by using the iconic symbol of the tipi.

Kay WalkingStick/Hudson River School

New-York Historical Society

170 Central Park West

at Richard Gilder Way (77th Street)

New York, NY

Now through April 14, 2024

This artistic dialogue showcases the ways in which Kay’s work both connects to and diverges from the

Hudson River School tradition and explores the agency of art in shaping humankind’s relationship to the land.

Deconstructing the Tipi

Hales Gallery

547 West 20th Street

New York, NY

Now through April 27, 2024

This solo exhibit centers around Kay's early abstractions from the mid-1970s,

engaging with her indigenous heritage by using the iconic symbol of the tipi.