To celebrate the memory of Raymond J. Steiner (a.k.a. Ray ~ 1933 to 2019), his writings, critiques and love of the arts, Cornelia Seckel and Myrna Haskell have combined their efforts to create a resource space of profiles and features that were originally published in ART TIMES, an international arts literary journal co-founded by Cornelia and Ray, which celebrated the arts for close to four decades. On occasion, readers will find past articles posted in this new space in Sanctuary, aptly titled Art Times Library.

Profile: Harriet Iles

By Raymond J. Steiner

ART TIMES June 2000

By Raymond J. Steiner

ART TIMES June 2000

|

Harriet Iles (2023)

Photo Courtesy: Harriet Isles |

IN OUR MAD rush for the new, the latest, the most 'avant' of cutting edge technology, art, political issue, or dietary fad, we have often forgotten our most elemental need for and understanding of the enigmatic wellspring from which we've sprung. Creatures woefully endowed with faulty senses and limited ken, we have forgotten the humility of our elders who warned against hubris, blindly barging into ever-new political schemes, world panaceas, and personal salvations. We abjure the reading of cranial bumps, the tossing of animal bones, the perusing of tea leaves and palms, the scanning of stars and planets, and the study of myth only to replace them with poll-taking and self-seeking pundits which and who are invariably wrong.

|

|

We have blithely turned over the world of myth to children—a questionable move if we consider the work of artist, myth-maker Harriet Iles. A sage once said of youth that it is wasted on the young—the same may be said of myth, for it does not only instruct the young, but if wisely interpreted, can act as guidance to the adult as well, can offer clues to those inner urges and needs that define us all, both young and old.

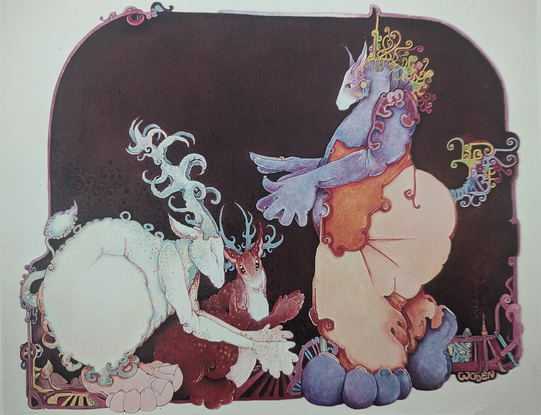

At first blush, one may pigeon-hole Iles's work as "children's book illustration" and judging them solely on their Beatrix Potter-like similarity, one might jump to such conclusions. It is true that Potter was an early influence on the young Harriet Iles whose early years were spent in England, but a closer look at the work of the two women will reveal just how far from children's stories Iles has come. Iles draws her imagery from a background that has little in common with the rustic cottage life found in the back yards and gardens of England depicted by Potter. Born in Washington, D.C., Iles, as noted above, moved to England at the age of two and lived there until the age of nine. Back in America, she tried to follow her parents' wishes of following a "normal" childhood, but after one year at college returned to England at the age of eighteen. Her "liberation" from convention was thus declared and established. |

Woden

Oil on Paper © Harriet Iles |

From England, Iles then went to Paris where she studied life drawing at the American Center for Students and Artists Abroad. Although a foundation in art was now established, she found the classes too confining, too academic to contain her burgeoning zest for freedom and adventure. Jazz (and jazz musicians) and an unfolding sense of wonder lured her to exotic shores, leading her on a seven-year journey throughout Europe and Asia. With a three-year stint in Afghanistan and travels in India, Kashmir and Nepal, Iles was not only deepening her visual vocabulary but learning something about herself and humankind as well. She settled in Woodstock, New York in the '70s, and, since then, has been sorting out the store of impressions her years on the road have garnered, "recording"—through sculpture and painting—those impressions in artistic terms.

Among the refining filters through which Iles has been sifting her experiences have been the studies of paleontology and archaeology, not through the eyes of academia but through the eyes of the devoted amateur. Shelves not entirely given over to veritable hordes of dolls and figurines—a collection which began in childhood and which serve as crude pre-cursors of her own work—hold tomes on both subjects, while back issues of magazines featuring such studies are opened and scattered about for easy reference. In addition to these items with which she surrounds her living and studio space, she has bookcases and vitrines holding the skulls and bones of present-day animals found at or near her home.

Iles keeps abreast of new discoveries, eagerly noting each bone and artifact unearthed from gravesites around the world. The past, as represented by dried bones, fossils, and remnants of graves, is not a dead thing for Iles, but a "living" testament not only of who we were, but of what we still are—modern technology and cultural accouterments notwithstanding. The discovery of woven fabrics and other hand-crafted adornments found buried in ancient tombs not only fascinates Iles but convinces her of the common roots of all peoples. Fabric patterns from pre-historic times, bodily ornamentation of tattoo or attached "jewels," even burial practices are still strangely "familiar," all, for Iles, testaments to a deep-seated and common urge within us that, despite our veneer of civilization, still speak to and through us.

It is, in fact, this unspoken world of commonality shared by peoples of all times and of all places that Iles's art depicts. She is in effect, spinning a new myth, a new world, in her art-order that is, ironically, in fact an old myth and an old world-order that pre-dates our more familiar ones of Greek and Hebrew gods and their interaction with man. Iles presents a world where man and beast are not disparate members of the animal kingdom, but melded into harmonious entities. Though they resemble "animals," these beings live in buildings and ride in vehicles. They discourse and hold office. They perform rites and they adorn themselves in manufactured goods. Their world appears to have a dignity and a decorum, yet they seem not "ruled" by governments nor threatened by the elements; their world, in short, is a benign one where strife and disorder seem foreign.

Their dress and their ceremonies might suggest a "religion" but it does not seem one that is concerned with a conventional "good" and "evil" opposition. All Iles's creatures appear to be exemplary and there are no indications of ogres, villains, or devils. Even when such suggestions of religion are explicit, Iles leavens the inference with humor, using such titles as "Mother Superior" or "Holy Goat" to lessen notions of sanctimonious religiosity. Far from being a world of high seriousness in which "sky" gods are invoked or propitiated, Iles's world is "peopled" by creatures firmly grounded on the earth, each invariably endowed with oversized feet that unmistakably fix them on a terrestrial plane. Though named "squirrel," "cat," "warthog" or whatever, these beings are actually amalgams, combinations of horse's heads, paws, hoofs, hands, and bodies both upright and on all fours that defy reality—but not credulity. They seem believable—even recognizable—yet each is formed by Iles's peculiar alchemy of imagination and fact.

Iles keeps abreast of new discoveries, eagerly noting each bone and artifact unearthed from gravesites around the world. The past, as represented by dried bones, fossils, and remnants of graves, is not a dead thing for Iles, but a "living" testament not only of who we were, but of what we still are—modern technology and cultural accouterments notwithstanding. The discovery of woven fabrics and other hand-crafted adornments found buried in ancient tombs not only fascinates Iles but convinces her of the common roots of all peoples. Fabric patterns from pre-historic times, bodily ornamentation of tattoo or attached "jewels," even burial practices are still strangely "familiar," all, for Iles, testaments to a deep-seated and common urge within us that, despite our veneer of civilization, still speak to and through us.

It is, in fact, this unspoken world of commonality shared by peoples of all times and of all places that Iles's art depicts. She is in effect, spinning a new myth, a new world, in her art-order that is, ironically, in fact an old myth and an old world-order that pre-dates our more familiar ones of Greek and Hebrew gods and their interaction with man. Iles presents a world where man and beast are not disparate members of the animal kingdom, but melded into harmonious entities. Though they resemble "animals," these beings live in buildings and ride in vehicles. They discourse and hold office. They perform rites and they adorn themselves in manufactured goods. Their world appears to have a dignity and a decorum, yet they seem not "ruled" by governments nor threatened by the elements; their world, in short, is a benign one where strife and disorder seem foreign.

Their dress and their ceremonies might suggest a "religion" but it does not seem one that is concerned with a conventional "good" and "evil" opposition. All Iles's creatures appear to be exemplary and there are no indications of ogres, villains, or devils. Even when such suggestions of religion are explicit, Iles leavens the inference with humor, using such titles as "Mother Superior" or "Holy Goat" to lessen notions of sanctimonious religiosity. Far from being a world of high seriousness in which "sky" gods are invoked or propitiated, Iles's world is "peopled" by creatures firmly grounded on the earth, each invariably endowed with oversized feet that unmistakably fix them on a terrestrial plane. Though named "squirrel," "cat," "warthog" or whatever, these beings are actually amalgams, combinations of horse's heads, paws, hoofs, hands, and bodies both upright and on all fours that defy reality—but not credulity. They seem believable—even recognizable—yet each is formed by Iles's peculiar alchemy of imagination and fact.

|

|

The "facts" of Iles's depictions are not only found in her meticulous drawings of animal parts—even the outsize hoofs and feet are anatomically "correct"—but in the detailed embellishments as well. Close inspection will disclose, among other things, runic inscriptions, Celtic design, and careful renditions of artifacts unearthed from archaeological digs. Though we have never seen these creatures, their habits and doings are vaguely accessible, understandable—they and their world "speak" to us, murmur intimacies to our deeper selves, remind us of a past that, though lost to written history, is somehow recorded in our DNA. They not only beguile us, but seem to have something to "say" to us, something of import that, if we misread the message, we might be losing (or forgetting) something of moment. If Iles's world is not "religious" (in any ordinary connotation), it is, in this sense, profoundly spiritual in that it speaks to the soul rather than to the senses. Though visual art is never easily captured in words, Iles's seems particularly elusive to explication. Because of its lack of actual reference to a material "reality," Iles's is almost a purely visual art, an art sufficient unto itself with analogous commentary or descriptive writing rendered either superfluous or untrustworthy.

|

The significance—for us—seems all the more relevant when we further note that the settings of these beings are largely underplayed by the artist. Though charmingly limned when included, neither land- nor townscape loom large in an Iles' painting, since, as she pointed out during our conversation, reproducing what she can see holds little attraction for her. It is the doings of her creatures rather than their environment that Iles wants us to note, wants us to interact with. It is as if she does not wish to localize her myth-making, hoping, perhaps, not to alienate us from a world that, somehow, is rightfully ours. In a real sense, it is not our world—just as the one we presently inhabit is equally not "ours"—but it is one that we might have if we "get the point." Ultimately, we all live in the world we create—and Iles is simply proposing one alternative we might choose. Surely it holds fewer terrors than that which most of us occupy.

All of Iles's dream-weaving, of course, comes from her "take" on the world—a view that is transformed by her imagination and fixed in ceramic, wood, or color and line. Prolific and seemingly tireless, Iles turns out drawing after drawing, each creature painstakingly outlined, each set aside until treated with oil or watercolor and properly framed as individual paintings designed—in spite of their obvious kinship—to stand alone. Essentially a three-dimensional artist—she has an extensive body of work that includes both clay models and wood carvings (an activity she yearns to re-connect with)—her creative drawings are given a further "believability" by virtue of their "solidity," their highly-skilled formality of depth and volume. Further than her skills in drawing, however, is the fact that each of her creatures appears lovingly limned, brought to "life" not to please Iles or her viewers, but rather in answer to their own peculiar entelechy. They, in effect, "believe" in themselves and we—both artist and viewer—have no reason to disbelieve.

Although she has latterly been concentrating on her paintings, it is perhaps her wood and clay sculptures that most clearly define the "message" contained in her work. Given a "reality" by their three-dimensionality (and the same meticulous attention to detail that is found in her drawings), many of Iles's sculptures—especially her ceramic pieces—are designed to be seen both inside and outside. Not only are they as "finished" as they are on their surfaces, but some reveal hidden "secrets" as well. Remove a head, for instance, and one might find a "precious" jewel cleverly set inside. An Iles character is, after all, an "inside" creature.

And, in the end, we all are.

All of Iles's dream-weaving, of course, comes from her "take" on the world—a view that is transformed by her imagination and fixed in ceramic, wood, or color and line. Prolific and seemingly tireless, Iles turns out drawing after drawing, each creature painstakingly outlined, each set aside until treated with oil or watercolor and properly framed as individual paintings designed—in spite of their obvious kinship—to stand alone. Essentially a three-dimensional artist—she has an extensive body of work that includes both clay models and wood carvings (an activity she yearns to re-connect with)—her creative drawings are given a further "believability" by virtue of their "solidity," their highly-skilled formality of depth and volume. Further than her skills in drawing, however, is the fact that each of her creatures appears lovingly limned, brought to "life" not to please Iles or her viewers, but rather in answer to their own peculiar entelechy. They, in effect, "believe" in themselves and we—both artist and viewer—have no reason to disbelieve.

Although she has latterly been concentrating on her paintings, it is perhaps her wood and clay sculptures that most clearly define the "message" contained in her work. Given a "reality" by their three-dimensionality (and the same meticulous attention to detail that is found in her drawings), many of Iles's sculptures—especially her ceramic pieces—are designed to be seen both inside and outside. Not only are they as "finished" as they are on their surfaces, but some reveal hidden "secrets" as well. Remove a head, for instance, and one might find a "precious" jewel cleverly set inside. An Iles character is, after all, an "inside" creature.

And, in the end, we all are.