Culture Crawl

This section includes a peek at the latest in theater, reviews of women-only exhibits, reflections on something interesting in film,

a snapshot of a special cultural or community event, etc.

a snapshot of a special cultural or community event, etc.

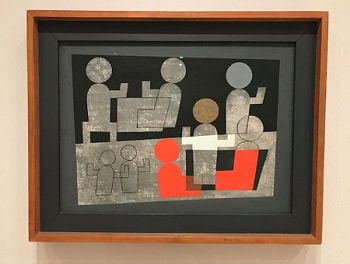

Sophie Taeuber-Arp's Cafe (1928)

By Sandra Bertrand

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) was one of the most multitalented of modern artists who ever lived – from applied arts teacher, textile and puppet-maker, mural and stained-glass designer, creator of furniture and building interiors, magazine editor, painter-sculptor to a master of geometric abstraction. But her greatest talent? She was a consummate marriage broker, wedding the lofty world of artmaking to life itself.

|

In her own words, “Only when we go into ourselves and attempt to be entirely true to ourselves will we succeed in making things of value, living things, and in this way help to develop a new style that is fitting for us.” And fittingly, the Museum of Modern Art has mounted a major retrospective, Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Living Abstraction, the first in over forty years, featuring some 300 works that reveal how she challenged the separation of fine art from craft and design – the very objects that enhance our daily lives.

Born in Switzerland to a pharmacist, Sophie, along with her family, emigrated to Germany when she was two. When WWI broke out, the family returned, settling in Zurich where she began her studies in a trade school for textile design. Her education continued in craft and design, both in Munich and Hamburg. While teaching embroidery design in Switzerland from 1916 to 1929, her textile creations were based on a formal grid structure. Early works such as Vertical-Horizontal Composition (1917) of wool on canvas show a remarkable sophistication of composition. Not one to strictly adhere to a set form, her designs soon became more open-ended. Whimsical boat motifs appeared as well as grid designs, like Free Rhythms (1919) that seem to take flight off the paper. |

Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943)

|

|

|

Many of her textile and graphic works are among the earliest Constructivist creations, along with those of such celebrated interpreters as Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich. But form alone never held total sway. Her sense of color was always prevalent. Abstract renderings of the human figure are infrequent but charming nonetheless. One can’t help but feel that no subject was beyond her willingness to interpret it in her own imitable style. Café (1928) gives the viewer tables of circle-headed patrons interacting in dynamic ways. Life itself was her canvas. Considering the number of examples encountered – pillows, beaded bags, necklaces, rugs, tablecloths and other miscellany – the curators have given more than ample space to her output. One room, for example, displays various lit windows of stained glassworks for private commissions. Ample copies of the accompanying catalog are to be found within easy reach throughout. |

|

Another room that has an instant draw for the visitor puts her marionettes on full display. They show a serious artists at play with her personages, not unlike some of the later creations from Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. It’s hardly surprising that such a curious artistic entrepreneur as Taeuber-Arp was active as a dancer and puppeteer in many performances at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire. Undoubtedly, her marriage to artist-poet Hans-Jean Arp in 2015 led to an expansion of personal contacts and wanderings, such as those with artist friends Kurt Schwitters and Hannah Hoch on the German island of Rugen, Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings on the Amalfi Coast in Italy, and Brittany excursions with Robert and Sonia Delaunay. Monuments and buildings held great interest for the artist, exemplified in such paintings as Siena Architecture (1921). |

|

Such social fermentation among other artists led to greater experimentation in her work, with active participation in the DADA movement. Centered in Zurich, the movement’s artists, poets and performers embraced its tenets as a reaction to the horrors and folly of war. Though satirical and nonsensical in nature, the intention was serious rejection of formal society. (Close friends with famed DADA artist Tristan Tzara, she was a co-signer of the Zurich DADA Manifesto.) One of her most famous works, Dada Head from 1920, resembles the small stands used by hatmakers of the day.

|

|

It is interesting to note that her decision to reverse the original doubled married name, Arp-Taeuber, became at least a symbol of sought-after independence for her. Even if artmaking was taking revolutionary steps during the early decades of the 20th century, a woman’s place in society still reeked of second-class citizenship. In order to obtain French citizenship for her husband, the couple moved to Strasbourg, which led to a number of interior design commissions. A few furnishings are on display but particularly elegant and arresting is footage of the interiors of the Aubette, entertainment complex. Today it is easy to see the beauty of modernist abstraction applied to the walls, staircases and ceilings of such a complex, but sad to learn of its demise, when more traditional eyes of the day could not comprehend its significance. Art historians later called the Aubette the “Sistine Chapel of abstract art.” |

When the Arps moved to Paris in 1929, she joined the abstract artist group, Cercle et Carré, (Circle and Square), where her non-objective paintings took precedence over earlier textual experiments, triangles and squiggles artfully intertwine with one another. Abstraction equaled freedom for this group: “Any attempt to limit artistic efforts according to considerations of race, ideology or nationality is intolerable.”

By the late 1930s, her work on paintings, collages and gouaches continued, but political tensions mounted. Before the couple fled to the south of France, finding refuge in a small town called Grasse a week before German troops advanced into Paris, she published the last of Plastique/Plastic, a magazine intended as a channel of communication between Europe and America. She continued to draw, but the climate grew more ominous and the Arps moved on to Zurich. Tragically, a few days before her fifty-fourth birthday, she died accidentally from carbon monoxide poisoning from a gas leak in her sleep.

It's hard to believe when confronted with her prolific career, that Sophie Taeuber-Arp was never given a solo show during her lifetime. She leaves behind a legacy of “living abstraction,” which is perfectly apt for an artist who valued art as life itself most of all.

By the late 1930s, her work on paintings, collages and gouaches continued, but political tensions mounted. Before the couple fled to the south of France, finding refuge in a small town called Grasse a week before German troops advanced into Paris, she published the last of Plastique/Plastic, a magazine intended as a channel of communication between Europe and America. She continued to draw, but the climate grew more ominous and the Arps moved on to Zurich. Tragically, a few days before her fifty-fourth birthday, she died accidentally from carbon monoxide poisoning from a gas leak in her sleep.

It's hard to believe when confronted with her prolific career, that Sophie Taeuber-Arp was never given a solo show during her lifetime. She leaves behind a legacy of “living abstraction,” which is perfectly apt for an artist who valued art as life itself most of all.

View Senior Curator Anne Umland’s thoughts about the exhibition below:

|

|

Sandra Bertrand is an award-winning playwright and painter. She is Chief Art Critic for Highbrow Magazine and a contributing writer for GALO Magazine. Prior to working for Sanctuary as Culture & Travel Editor, Sandra was a Featured Artist in May 2019.