Play & Book Excerpts

|

|

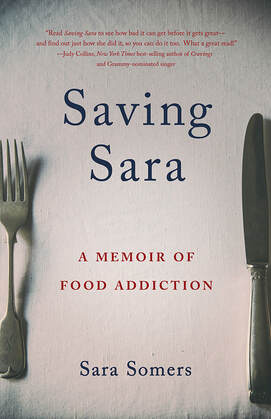

Saving Sara

(She Writes Press)

© 2020 Sara Somers

Note: An interview link is included at the end of this excerpt:

By the time I was fifteen years old, there was no doubt in my mind that something was drastically wrong with me. I thought it was the family I’d been born into. I thought eating was the solution to my misery, even though it was obvious to everyone else that the way I thought about food and was gaining weight wasn’t normal. I didn’t want anyone to see or to know what I was doing. I was too ashamed to admit what I was doing. I wanted to be cured of suffering, cured of my weight problems, but I didn’t want any suggestions from anyone. My emotional state of being was a roller coaster. I might have been diagnosed as bipolar, my swings were so dramatic. But I wasn’t bipolar. I was a food addict.

I had moments of joy that made me high, followed by deep depressions…The word “moderation” did not exist for me. I knew the definition of the word but when my father would helplessly watch me scarfing down food and offer, “Can you try and eat in moderation?” the answer was no. I was completely incapable. The shame made it impossible for me to admit to him that I felt powerless, that I was scared and felt hopeless. I didn’t want him saying anything to me, reminding me of that powerlessness. So, I began my eating/bingeing in secret - at least, I thought I did.

Bingeing is an intimate act, which is one of the ways it’s a different kind of addiction from alcoholism. Alcoholics can succumb to their addiction at bars and be considered the life of the party. The beginning stages of alcoholism are socially acceptable. Food addicts, on the other hand, always binge alone. The act of bingeing is both compulsive and shameful. Even in the midst of a binge, we are trying with every ounce of willpower not to binge.

As my bingeing progressed, I would often be sitting on the floor in front of the fridge, or on my bed surrounded by cookie crumbs, crying my eyes out, while compulsively continuing to binge. I desperately wanted things to be different. I wanted to be well, not to be engaging in these behaviors, and yet I couldn’t stop. If you think this sounds a lot like insanity, you’re right. It is definitely a type of insanity.

~~~

My family loved ice cream. My mother would buy it in half-gallon rectangular boxes. There was always a box of coffee, a box of vanilla, and often the triumvirate of vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry in the freezer. After our family dinner, one parent would serve each of us a single helping for dessert - but that was never ever enough for me.

Wanting more doesn’t accurately describe the single-minded obsession of the addict - of wanting what you want now - or how that can drive your whole evening. In our split-level home, my bedroom was a half floor below the kitchen, whereas my parents’ and my sister’s bedrooms were a half floor above. Down in my room, I’d wait impatiently, supposedly doing homework, until it seemed to me that all was quiet in the kitchen. Then I’d sneak back up, go to the freezer, and retrieve the half-gallon carton of ice cream. Standing in front of the freezer, often with the door still open, I’d grab a spoon, open the opposite end from the one already opened, and eat as much and as fast as I could. That’s all I want, I’d tell myself, as if I had some control over the quantity. I’d really mean it at the moment I thought it, even though I hadn’t tasted anything and it had not been satisfying at all. I ate so fast that I often got brain freeze. Then I’d hold my head under the faucet, lapping up warm water until my head stopped hurting.

This all took place in less than five minutes. All the while, I was in a state of intense anxiety, wondering if my parents would hear me and come investigate what was going on. I’d creep back down to my room, returning to my homework that I hadn’t started. But it was impossible to focus when all I was thinking about was the ice cream in the freezer, calling my name. I might hold out for as much as fifteen minutes, but then I’d be sneaking back upstairs to the freezer and doing it all over again. Eating fast and furious, getting brain freeze, running warm water, gulping it down, and escaping back downstairs before my parents were any the wiser.

This repeated itself until I realized that there was only half an inch of ice cream between my binge side and the side that had been opened for the family. Then, with great effort and even greater fear of the consequences, I left the ice cream box as it was.

Nobody ever said a word to me about the food that disappeared. I thought I was getting away with something. I know I terrorized my parents and my sister. I know I made it impossible for anyone to talk to me. I had to have the last word. I screamed in rage if I thought one or the other parent was picking on me. I wouldn’t hesitate to lie, even when the truth was obvious. I’d slam doors and lock myself in my room.

I didn’t have a clue what was wrong. If my dad suggested it might be lack of willpower, I flew off the handle. Everything he said that he thought might be helpful only served to bring to my attention the fact that my behavior felt completely out of my control. I hated myself and I hated everyone in my family. My home was a constant battleground. There were no words at that time for families that lived with and survived an active addict, but I’m sure all four of us were suffering from PTSD by the time I graduated high school.

I had moments of joy that made me high, followed by deep depressions…The word “moderation” did not exist for me. I knew the definition of the word but when my father would helplessly watch me scarfing down food and offer, “Can you try and eat in moderation?” the answer was no. I was completely incapable. The shame made it impossible for me to admit to him that I felt powerless, that I was scared and felt hopeless. I didn’t want him saying anything to me, reminding me of that powerlessness. So, I began my eating/bingeing in secret - at least, I thought I did.

Bingeing is an intimate act, which is one of the ways it’s a different kind of addiction from alcoholism. Alcoholics can succumb to their addiction at bars and be considered the life of the party. The beginning stages of alcoholism are socially acceptable. Food addicts, on the other hand, always binge alone. The act of bingeing is both compulsive and shameful. Even in the midst of a binge, we are trying with every ounce of willpower not to binge.

As my bingeing progressed, I would often be sitting on the floor in front of the fridge, or on my bed surrounded by cookie crumbs, crying my eyes out, while compulsively continuing to binge. I desperately wanted things to be different. I wanted to be well, not to be engaging in these behaviors, and yet I couldn’t stop. If you think this sounds a lot like insanity, you’re right. It is definitely a type of insanity.

~~~

My family loved ice cream. My mother would buy it in half-gallon rectangular boxes. There was always a box of coffee, a box of vanilla, and often the triumvirate of vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry in the freezer. After our family dinner, one parent would serve each of us a single helping for dessert - but that was never ever enough for me.

Wanting more doesn’t accurately describe the single-minded obsession of the addict - of wanting what you want now - or how that can drive your whole evening. In our split-level home, my bedroom was a half floor below the kitchen, whereas my parents’ and my sister’s bedrooms were a half floor above. Down in my room, I’d wait impatiently, supposedly doing homework, until it seemed to me that all was quiet in the kitchen. Then I’d sneak back up, go to the freezer, and retrieve the half-gallon carton of ice cream. Standing in front of the freezer, often with the door still open, I’d grab a spoon, open the opposite end from the one already opened, and eat as much and as fast as I could. That’s all I want, I’d tell myself, as if I had some control over the quantity. I’d really mean it at the moment I thought it, even though I hadn’t tasted anything and it had not been satisfying at all. I ate so fast that I often got brain freeze. Then I’d hold my head under the faucet, lapping up warm water until my head stopped hurting.

This all took place in less than five minutes. All the while, I was in a state of intense anxiety, wondering if my parents would hear me and come investigate what was going on. I’d creep back down to my room, returning to my homework that I hadn’t started. But it was impossible to focus when all I was thinking about was the ice cream in the freezer, calling my name. I might hold out for as much as fifteen minutes, but then I’d be sneaking back upstairs to the freezer and doing it all over again. Eating fast and furious, getting brain freeze, running warm water, gulping it down, and escaping back downstairs before my parents were any the wiser.

This repeated itself until I realized that there was only half an inch of ice cream between my binge side and the side that had been opened for the family. Then, with great effort and even greater fear of the consequences, I left the ice cream box as it was.

Nobody ever said a word to me about the food that disappeared. I thought I was getting away with something. I know I terrorized my parents and my sister. I know I made it impossible for anyone to talk to me. I had to have the last word. I screamed in rage if I thought one or the other parent was picking on me. I wouldn’t hesitate to lie, even when the truth was obvious. I’d slam doors and lock myself in my room.

I didn’t have a clue what was wrong. If my dad suggested it might be lack of willpower, I flew off the handle. Everything he said that he thought might be helpful only served to bring to my attention the fact that my behavior felt completely out of my control. I hated myself and I hated everyone in my family. My home was a constant battleground. There were no words at that time for families that lived with and survived an active addict, but I’m sure all four of us were suffering from PTSD by the time I graduated high school.

|

Photo Credit: Henrie Richer

|

Sara Somers suffered from food addiction from age nine to age fifty-eight. She has been in food recovery since 2005. In a double life of sorts, Sara worked as a licensed psychotherapist in the San Francisco Bay Area for thirty-four years. After finding recovery, she moved to Paris, France, where she currently lives.

Sara writes a blog titled Out My Window: My Life in Paris. When she’s not writing, she volunteers at the American Library in Paris, enjoys the cinema, reads prolifically, and follows her favorite baseball team, the Oakland Athletics. Most importantly, Sara devotes time each day to getting the word out about food addiction and helping other food addicts. Saving Sara is her first book. Learn More About Sara's Journey:

|